(September 2022)

Concerning a nineteenth century loom and the recollections of a hemp worker in the French Alps.

Ecomusée du Clos Parchet

The star exhibit of the Ecomusée du Clos Parchet is the building itself, situated on a mountainside in the Haute Savoie, built in 1815 and now preserved as a typical example of a traditional Savoyard farmhouse. The form of these farmhouses evolved over centuries to be exquisitely fit for purpose. The stone-built bottom storey is divided into two, with a byre for cattle, sheep & pigs on the north side, and living quarters on the south. A tapering chimney, large enough at the bottom for smoking hams, runs up from the kitchen through the timber built barn which comprises the upper story and where winter feed was stored. The building now houses an astonishing array of old tools and household items, including a loom dated 1868.

Our museum guide Nora explained how most farmers in the region had two farms, one in the valley and another on the mountainside. Hemp was one of the crops grown in the valley, for processing into yarn for weaving. The museum has an interesting collection of hemp processing equipment and antique hempen textiles, including tablecloths, blankets and items of clothing.

The growing and weaving of hemp was once common across Europe. In Britain it had largely disappeared by the early 19th century, but before that the english word ‘linen’ was used to refer to cloth made from either flax or hemp, and the latter was easier to grow. I have not found any examples of old hempen cloth in Britain.

Le Chanvre

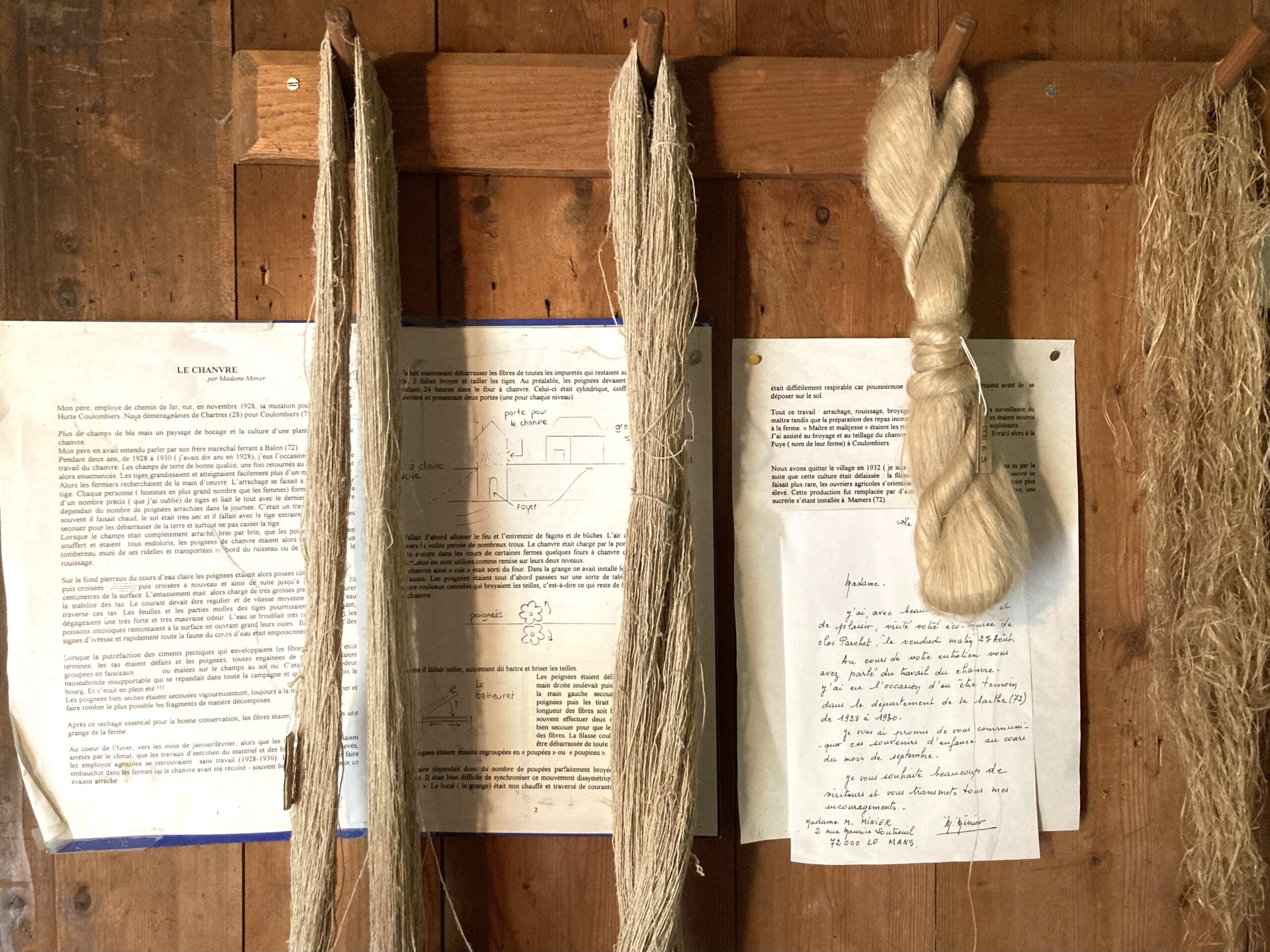

Pinned to the museum wall is a letter from a Madame Minier who, after visiting the museum in 2000, was moved to share her experience of harvesting and processing hemp. She had worked on a farm in Coulombier, Pays de la Loire, in North West France, in 1928-30.

Here is my translation of Madame Minier’s story:

LE CHANVRE

by Madame Minier

My father, a railway employee, was transferred to the Gare La Hutte Coulombiers in November 1928. We moved from Chartres to Coulombiers. I swapped a landscape of wheat fields for one of pasture, and the cultivation of a new crop – hemp. My father had heard about it from his brother who was a farrier in Balon.

For two years, from 1928 to 1930 (I was ten years old in 1928), I had the opportunity of doing hemp work. Fields of good quality soil were ploughed and then sown. The stems grew tall and easily reached over a meter in height. The farmers were looking for labour. The uprooting was done by hand, a stem at a time. Each person (more men than women) would make bundles of a specific number (which I forget) of stems and tie them all together with the last strand. Your earnings depended on the number of bundles pulled out during the day. It was very arduous work, often it was hot, the soil was very dry and it was necessary to extract the roots with the stem and shake them to get rid of the soil, and above all not to break the stems.

By the time the field had been completely uprooted, a stem at a time, and your wrists were aching as a result, the bundles of hemp were piled up in a truck fitted with its sides, and transported to the edge of the stream or the river, for retting.

The bundles were then placed side by side on the stony bottom of the clear stream, then crossed and crossed again and so on until about 20 to 30 centimeters from the surface. The piles were then loaded with very large stones to ensure their stability. The current had to be regular and of medium speed for the water to pass through these piles. The leaves and the soft parts of the stems rotted and in doing so gave off a very strong and very bad smell. The water became cloudy very quickly and the poisoned fish rose to the surface, opening their gills wide. They showed signs of drunkenness and quickly all the fauna of the river was poisoned.

When the putrefaction of the pectic cement which enveloped the hemp fibers was finished, the piles were undone and the bundles, all sheathed in rot, were grouped in bigger bundles or spread out on the bare ground. There was then an unbearable nauseating smell that spread throughout the countryside and sometimes reached the town. And it was in the middle of summer!!!

Once well dried the bundles were shaken vigorously, still by hand, to loosen and remove as many fragments of decomposed material as possible. After this drying, essential for preserving the fibres, the bundles were stored in a barn.

In the heart of winter, around the months of January / February, when the agricultural work had stopped because of the weather, and once the maintenance work on equipment and buildings was completed, the agricultural employees found themselves without work. They would then be hired on the farms where the hemp had been harvested – often many of them relocating for the work.

It was now necessary to rid the fibers of all the impurities that remained. For this it was necessary to crush and cut the stems. First, the bundles had to be heated for 24 hours in the hemp oven. This was cylindrical, topped with a pepperbox roof and with two doors (one for each level).

It was first necessary to light the fire and maintain it with fagots and logs. Hot air rose through a vault pierced with numerous holes. The hemp was loaded through the top door. There are still a few farmyards with hemp ovens that are no longer maintained or are used as sheds on both levels.

The “cooked” hemp was then taken out of the oven. In the barn we had installed the rollers and the breaking machines (les teilleuses). The bundles were first passed over a kind of table and between two or four fluted rollers which crushed the hemp – that is to say what remained of the bark of the hemp stalks.

Then it was necessary to break or beat the stalks.

The bundles were untied. While the right hand lifted and then lowered the blade, the left hand shook the bundles side to side and then pulled them so that the entire length of the fibers was well treated. It was often necessary to make two or three passages and to shake well to detach the bark from the fibers. The pale straw-colored tow had to be cleared of all impurities.

These bundles were then grouped into “poupées” ou “poupines”. (Note: I cannot find equivalent English terms for poupées or poupines.)

The salary therefore depended on the number of “poupées” perfectly crushed and cut during the day. It was very difficult to synchronize this asymmetrical movement, you had to get the hang of it. The room (the barn) was unheated and draughty. The atmosphere was hard to breathe because it was dusty: the light hemp fragments fluttered in the air before coming to rest on the ground.

All this work: uprooting, retting, crushing and breaking, was done under the supervision of the master while the mistress prepared the meals. The workers were fed on the farm. The owner-operators were referred to as Master and Mistress (Maître et maîtresse). I worked at the breaking and scutching of hemp at the farm called La Fuye, owned by Mr. & Mrs. Evrard, in Coulombiers.

We left the village in 1932 (I went to a boarding school in 1930) and later learned how the cultivation of hemp declined: the fibre sold less well, labor became scarce, farm workers moved to the city and demanded a higher salary. Hemp was was replaced by other crops, including beet, a sugar factory having been set up in Mamers.

(End)