(February 2021)

I recently bought a second-hand copy of ‘Mechanics for Textile Students’ by W.A. Hanton (1954). When it arrived through the letterbox I found some of the pages stamped by a previous owner: HOWARD & BULLOUGH SCHOOL – ACCRINGTON.

Accrington is a small town in north-east Lancashire midway between Blackburn and Burnley. It gives its name to the Accrington brick, a hard red engineering brick which I associate with the street of terraced houses in Mill Hill, Blackburn, where my grandfather lived, and where my mother grew up. The houses were built in the early 1900’s to house workers from the local textile mills. They were small, opening directly onto the street, with no gardens and a toilet in the back yard. My grandmother, who died before I was born, had moved to Mill Hill while Grandad was in France for the last years of the First World War. As a boy he had started work at a nearby cotton mill in 1902. Part-time at twelve, full-time at thirteen. He hated the work. During his first year he had the palm of his hand torn off in a machine.

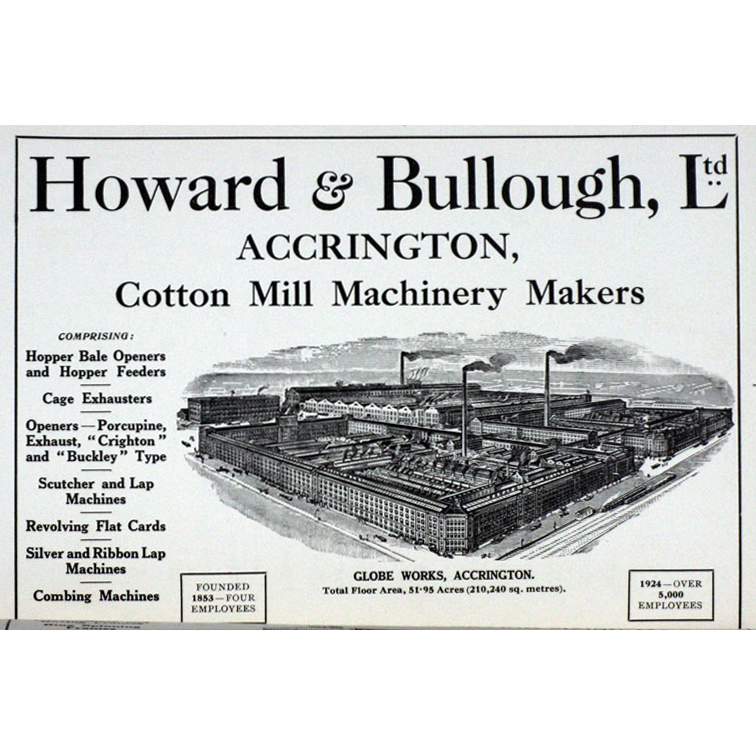

Howard & Bullough Ltd used to be the world’s biggest manufacturer of cotton mill machinery. Their factory in Accrington, which closed in 1993, had dominated the town, occupying 52 acres and employing 6,000 workers. A school for apprentices was established in the 1880’s and amalgamated into the Accrington Technical School in 1892. There appears to have been an in-house training school operating in the 1950s and 60s, which must be where my book was stamped.

The chapter on Coil Friction in ‘Mechanics for Textile Students’ would have been useful a few months ago when I was trying to perfect my new selvage bobbins. Selvage bobbins are mounted on the loom on either side of the warp and allow a few threads to be independently tensioned to help make a good selvage. The tensioning mechanism consists of a weighted cord wound round the bobbin, and it relies in coil friction. I eventually got them to work by experimenting with different kinds of cord, different sized weights, and different materials for the bobbin, but it might have been easier with the benefit of the theories, equations and diagrams in the book.

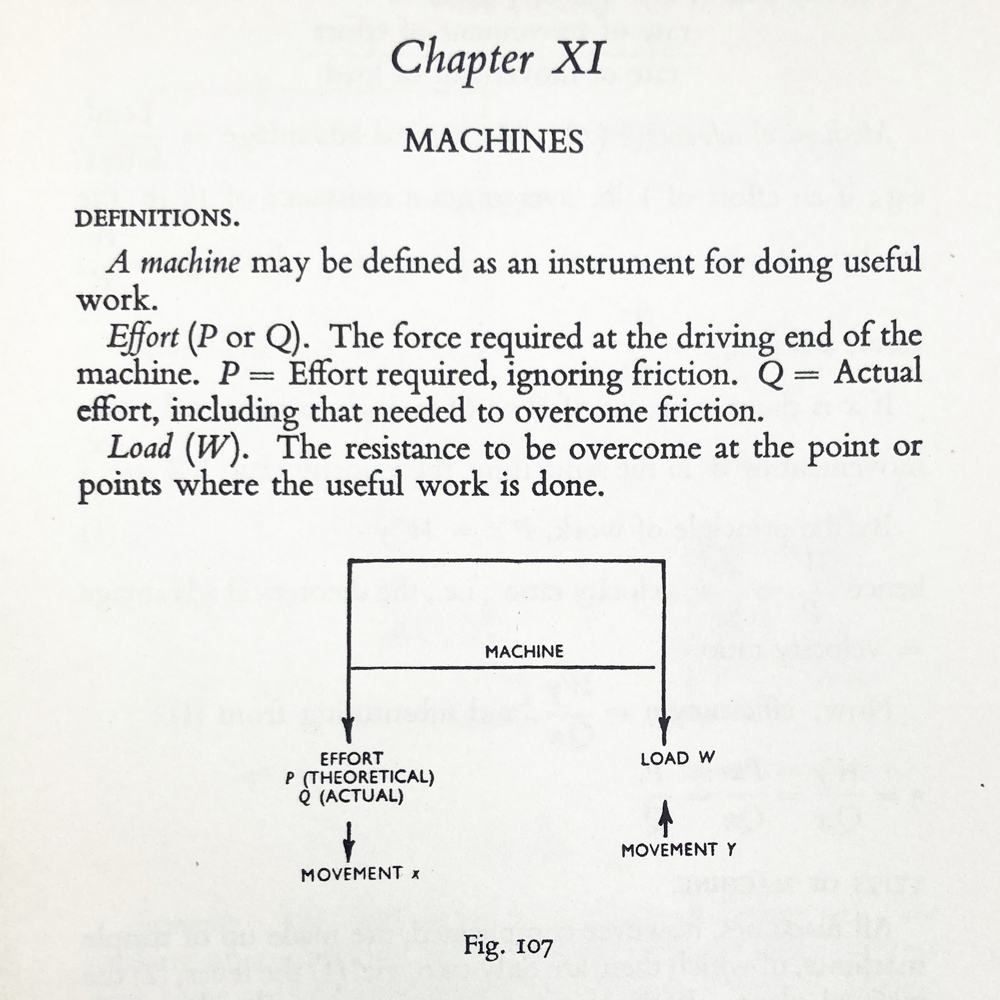

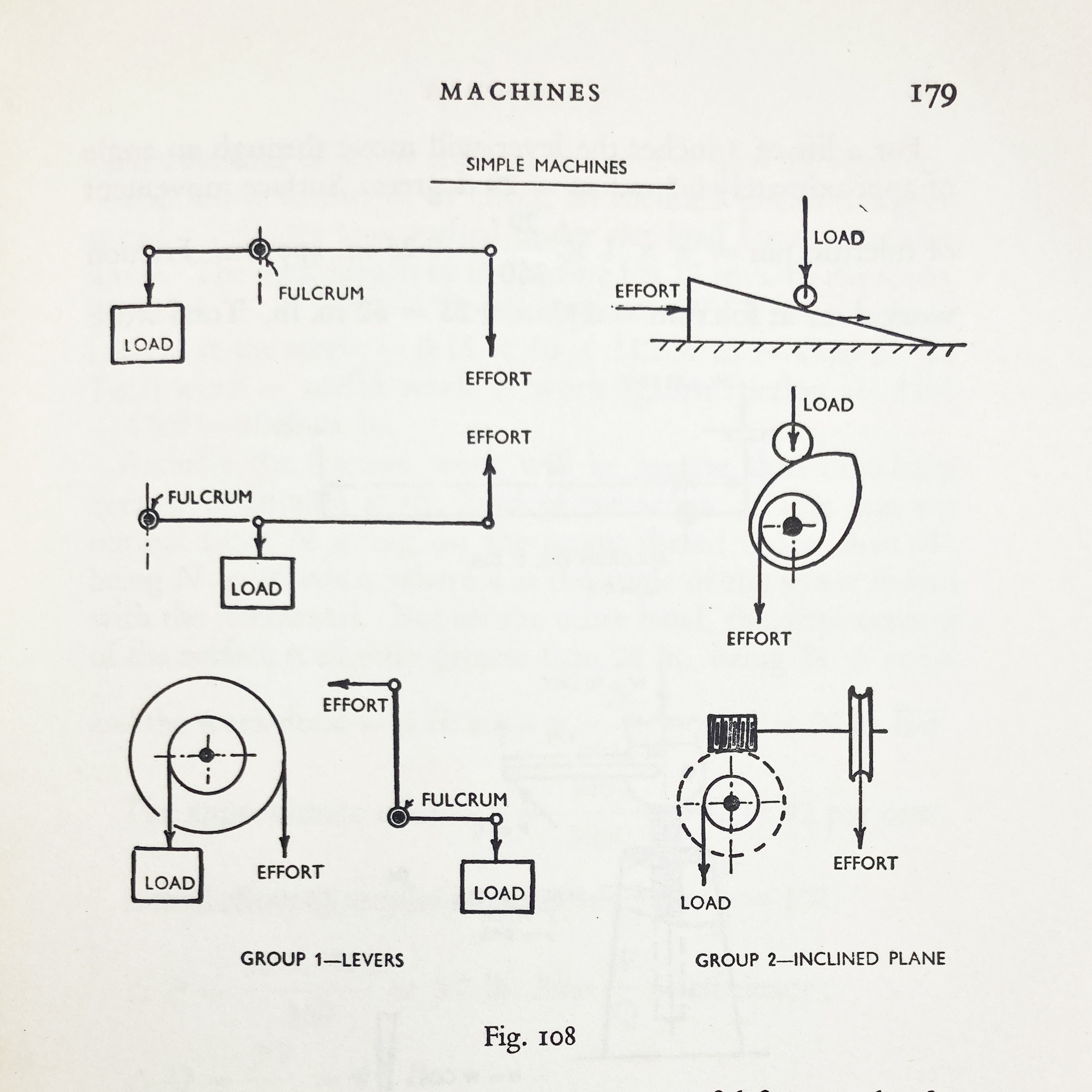

I’ve occasionally wondered if a handloom such as mine counts as a tool or a machine, and I guess it depends on your definitions. According to W.A. Hanton “a machine may be defined as an instrument for doing useful work” and “all machines, however complicated, are made up of simple machines, of which there are only two, viz. (1) the lever, (2) the inclined plane. Each of these may, however, be disguised.” Loom treadles and pulleys are kinds of lever, so from an engineering perspective a loom is a complex machine made up of several simple machines, each doing mechanical work.

Of course there are other kinds of useful work besides the lifting of weights. Some of the work done by a loom is informational rather than mechanical – such as selecting which warp threads to lift at the same time.

Diagrams are instruments for doing cognitive work, so these diagrams of machines are themselves machines of a sort. They get their leverage by showing only what is essential and leaving out everything else. They don’t make a noise and you can’t get your hand stuck.