(February 2022)

The following is a transcription of the film Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 1: Schären der Kette, with my translation of the original German commentary presented alongside stills from the corresponding scenes in the film.

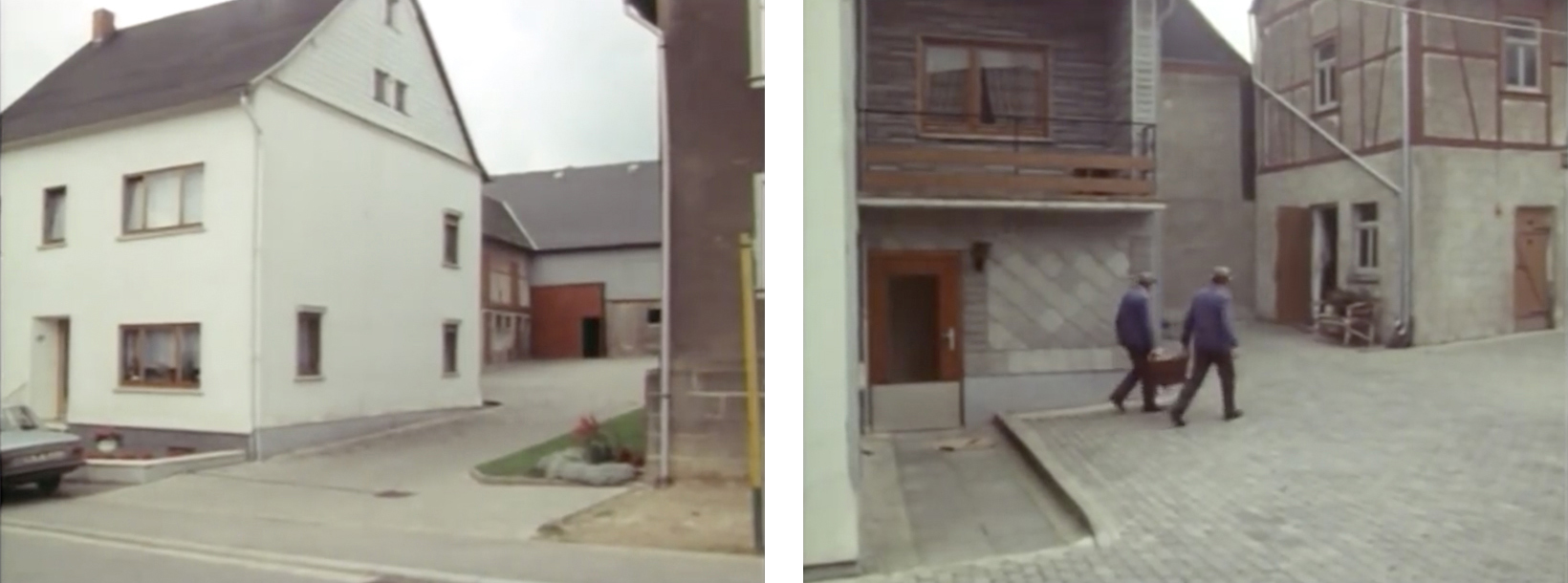

The film is the first in a series recording the re-enactment of traditional linen weaving in the town of Dickenshied in 1978/9, produced by Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

All images courtesy of Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

Watch the original film here. For more information about the films read this.

Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 1: Schären der Kette

Rural Linen Weaving: 1: Winding the Warp

Commentary

Dickenschied is located in the Hunsrück region, near the town of Simmern. Flax was grown and processed into linen in this area until the second world war, and even to some extent in the post-war years. As a result the skills of rural linen making survived here after they had been forgotten elsewhere.

Until the beginning of the 20th century linen weaving was of great importance in the Rhineland hill country. It was mainly practiced as a sideline providing linen for the weavers’ own use.

The preparatory work for weaving is very time-consuming and requires great skill and care. For the film, these activities are re-enacted in the courtyard at 27 Kirchbergstrasse. Wilhelm Mosel and Otto Klos can remember how weaving was done in Dickenschied during their childhoods before the Second World War. Here they demonstrate the first of several operations involved in linen manufacture: the preparation of the warp.

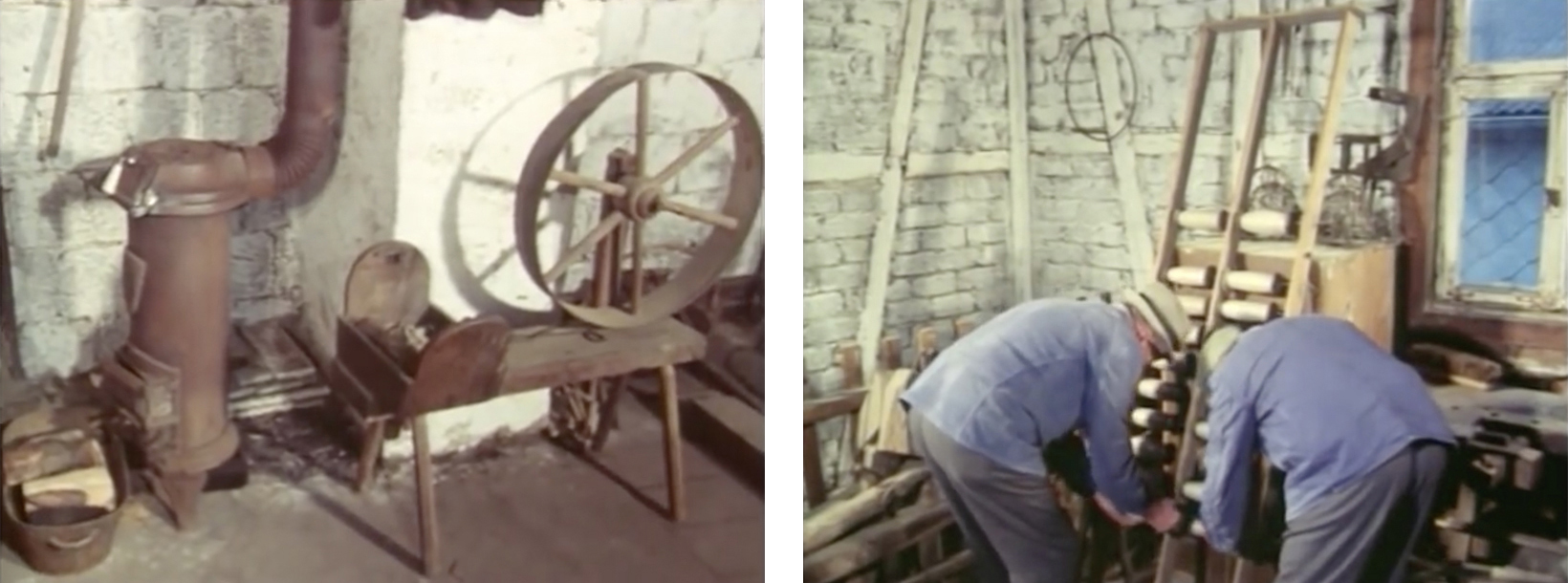

Warp winding, referred to as Zierlen in the Hunsrück region, was done outside in good weather, or in a barn or other large space. Here it takes place in the workshop (Bosselkammer), which is also used as a weaving room.

The warp consists of parallel threads of equal length to be stretched on the loom. The required amount of linen yarn is wound on large wooden spools. Each spool can hold up to 2000m of yarn. It has been laboriously spun on spinning wheels during the winter. The spools are fixed in the creel with wire pins.

The work related to linen weaving, such as yarn spinning, warping and spool winding, as well as the weaving itself, was mainly done in the autumn and winter when there was little farm work to be done.

The number of spools required depends on the weight of cloth to be made. At least 20 spools are required for a simple linen fabric like that being made here.

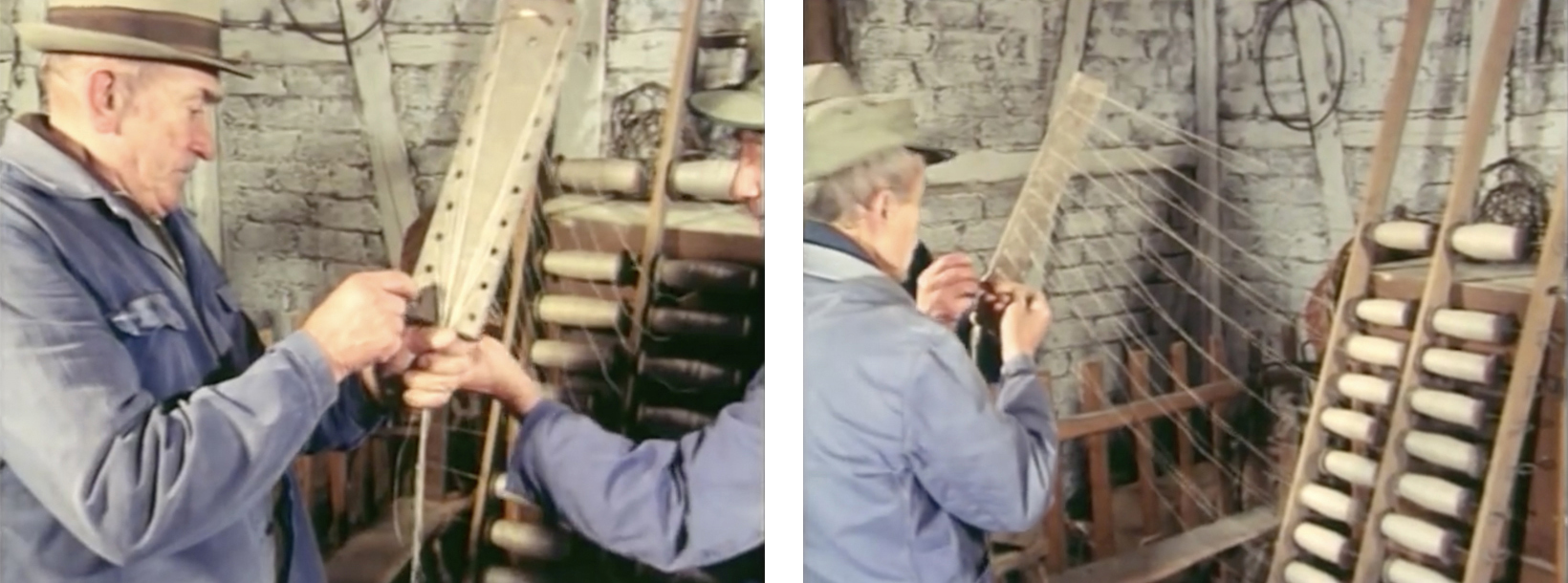

A warping board or paddle (Inreffbrett) is used to guide the individual threads in parallel. Linen yarn from each spool is pulled separately through a hole in the paddle. This helps avoid tangling the yarn.

Once all the threads have been pulled through, Wilhelm Mosel ties the bundle of threads together. He places the knot on the warping mill (Schärkrone, also called Zettelkrone or Zierlkrone). This is a large rotating wooden frame.

Now the cross (das Fadenkreuz) (1) must be formed. The weaver divides the group of threads into two halves with his index finger and thumb. The cross is placed over two wooden pegs.

Otto Klos now turns the warping mill in a clockwise direction. The bundle of threads is slowly wound on. Wilhelm Mosel guides the yarn downwards.

The number of revolutions depends on the desired length of cloth. In this case, the circumference of the mill is five cubits, approximately 3.35m (2). Four turns are needed for a 13.5 m long cloth.

When they get to the lower end of the mill the bundle of threads is looped around a wooden peg.

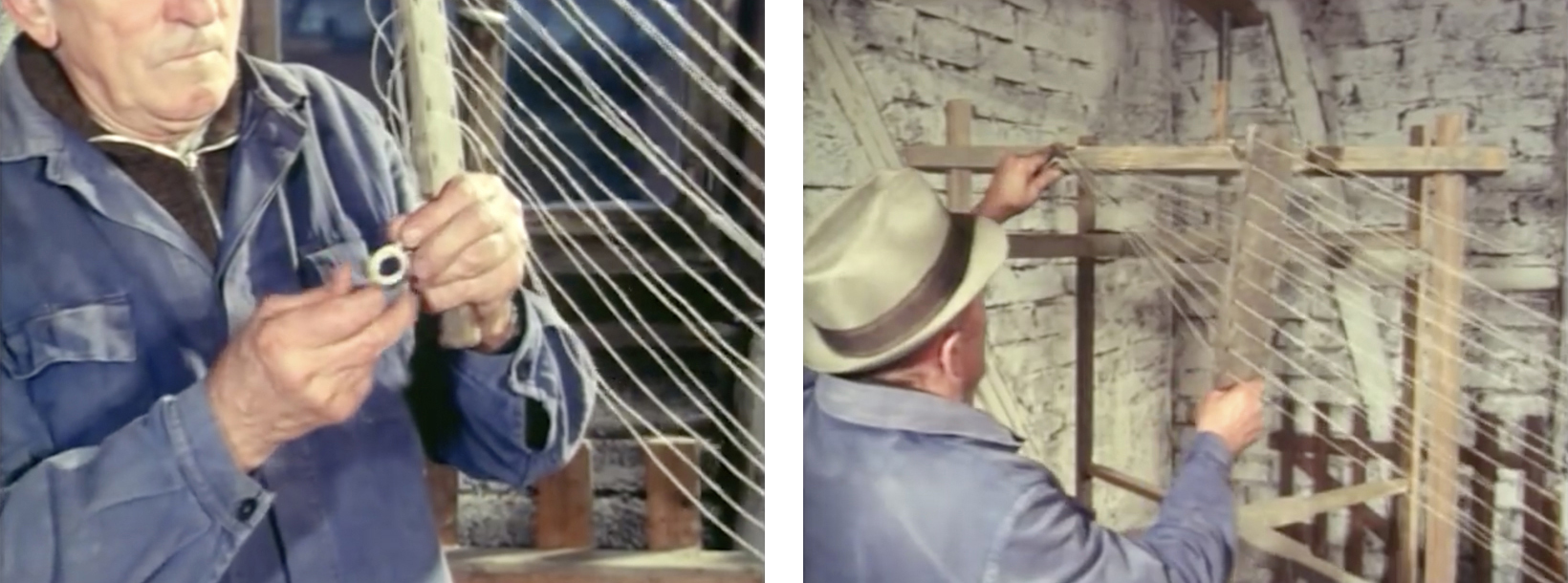

Otto Klos now turns the mill anticlockwise and the weaver slowly guides the yarn back up. The 40 threads lying next to each other after being wound up and down once are referred to as a gang (ein Gang) (3). They all have the length of the future cloth. The process is now repeated several times.

At the corners of the mill each group of threads is always placed alternately higher or lower than the previous group. If they were wound on top of one another, the outer threads, wound last, would be longer than the inner ones.

Each time, the weaver forms the cross at the top with his fingers. Care must be taken when winding to ensure that the threads are evenly tensioned.

The term Schären is derived from Fadenschar (the bundle of threads wound onto the mill). It has nothing to do with the large metal shears (scheren) that were used to remove the fine protruding hairs on the surface of finished woollen cloth.

Otto Klos marks the finished gang with chalk.

In the case of very wide or fine fabrics with several thousand warp threads, the warp had to be made in two or three sections because the yarn would not fit onto the warping mill all at once. For simple linen fabrics for home use, like this one, one section is usually enough.

The number of gangs depends on the loom harness and the width of the fabric. Here they are making a warp with 36 gangs, i.e. 36 courses of 40 threads each. So the warp will have 1440 threads.

When winding, care is taken to ensure that the threads remain evenly taut and do not become tangled.

Any broken threads must be repaired immediately. This is done with the weaver’s knot.

A cord is inserted at the end of the warp after every 5 loops. This makes it easier to keep count while winding the warp.

As soon as a spool is empty, the men must wind new yarn with the winding wheel. Otto Klos turns the drive wheel with his right hand and guides the thread evenly onto the bobbin with his left.

In the 19th century, when commercial weaving developed as a separate trade, warping was done in the factory. The hired weaver picked up the warp and later brought the finished cloth to the employer. In rural linen production the weaver usually made the warp himself.

The weaver checks the number of courses. The 36 that are needed have now been wound.

After forming the cross, Wilhelm Mosel cuts the threads and ties the upper and lower halves together.

He inserts a cord into the loops of the cross. This preserves the division of the yarn into upper and lower halves when the warp is removed from the warping mill. This is important because exactly half of the yarn will later be pulled through the first shaft of the loom and the other half through the second shaft. In this way, simple plain weave can be made, with the threads running alternately up and down.

A cord is also inserted at the end of the warp.

The men must remove the upper crossbar to be able to unwind the tight warp from the mill.

All the equipment needed for warping, such as the bobbin creel, paddle and warping mill, used to be made by village carpenters. Because the equipment was simply made the weaver could usually carry out repairs himself.

The weaver slowly unwinds the yarn, looping it into a braid-like chain. He must be careful not to tangle or knot the threads. This way of chaining the warp makes it more compact.

The warp, which is more than 10 metres long, is shortened to a third of its length. The bulky warping mill must be put away after use to make room for setting up the loom.

Otto Klos pulls the excess yarn out of the paddle and winds it back onto the spools. It will either remain on the spools until the next warping operation, or it will be wound with the winding wheel onto smaller weft bobbins for weaving. Otto Klos also puts the creel aside until the next time it is needed.

This completes the first stage of the weavers’ process.

Notes:

- Several alternatives often present themselves when translating the technical terms of weaving. Where appropriate I have used the alternative closest to the German to draw out the shared etymologies. Thus cross for Fadenkreuz, rather than lease. A warp has two crosses, the porrey cross, dividing indidual threads as here at the top of the warping mill, and the portée cross, dividing the warp into gangs, or portées, at the bottom of the mill.

- A cubit is 18 inches or 457mm, so 5 cubits are actually about 2.3m, not 3.5m.

- The german word used here is Gang. The english word gang, designating a group of threads warped together, is used by John Duncan in Practical & Descriptive Essays on the Art of Weaving (1808). It is sill used by some weavers, altough the term portée is perhaps more common. (see note 1 above).