(February 2022)

The following is a transcription of the film Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 2: Aufschlagen des Webstuhls, with my translation of the original German commentary presented alongside stills from the corresponding scenes in the film.

The film is the second in a series recording the re-enactment of traditional linen weaving in the town of Dickenshied in 1978/9, produced by Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

All images courtesy of Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

Watch the original film here. For more information about the films read this.

Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 2: Aufschlagen des Webstuhls

Rural Linen Weaving in Germany: 2: Building the Loom

Commentary

In late autumn, when the farm work in the Hunsruck area was finished, preparations for linen weaving could begin. In the 19th century several families here in Dickenschied owned there own looms, weaving linen mainly as a sideline. The loom was assembled between Old Halloween (1) and Christmas.

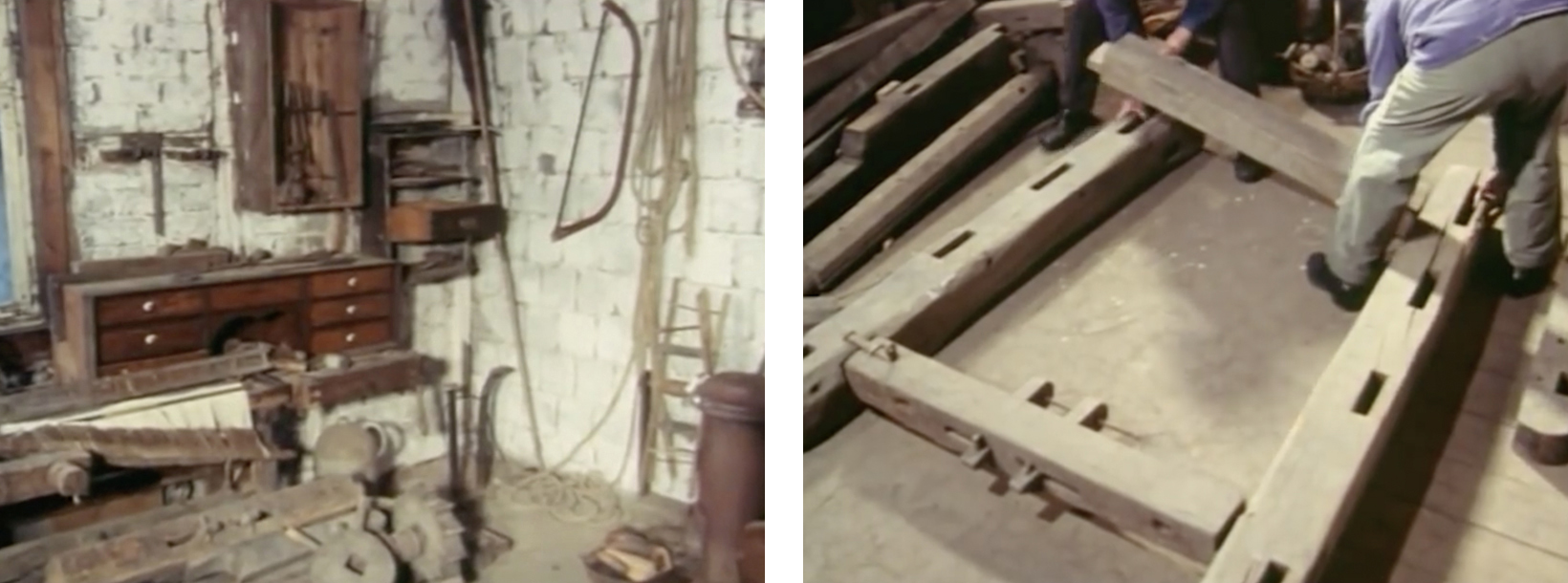

This was usually done in one of the rooms of the house, such as the living room, or in a workshop – the Bosselkammer. Few families had a separate weaving room.

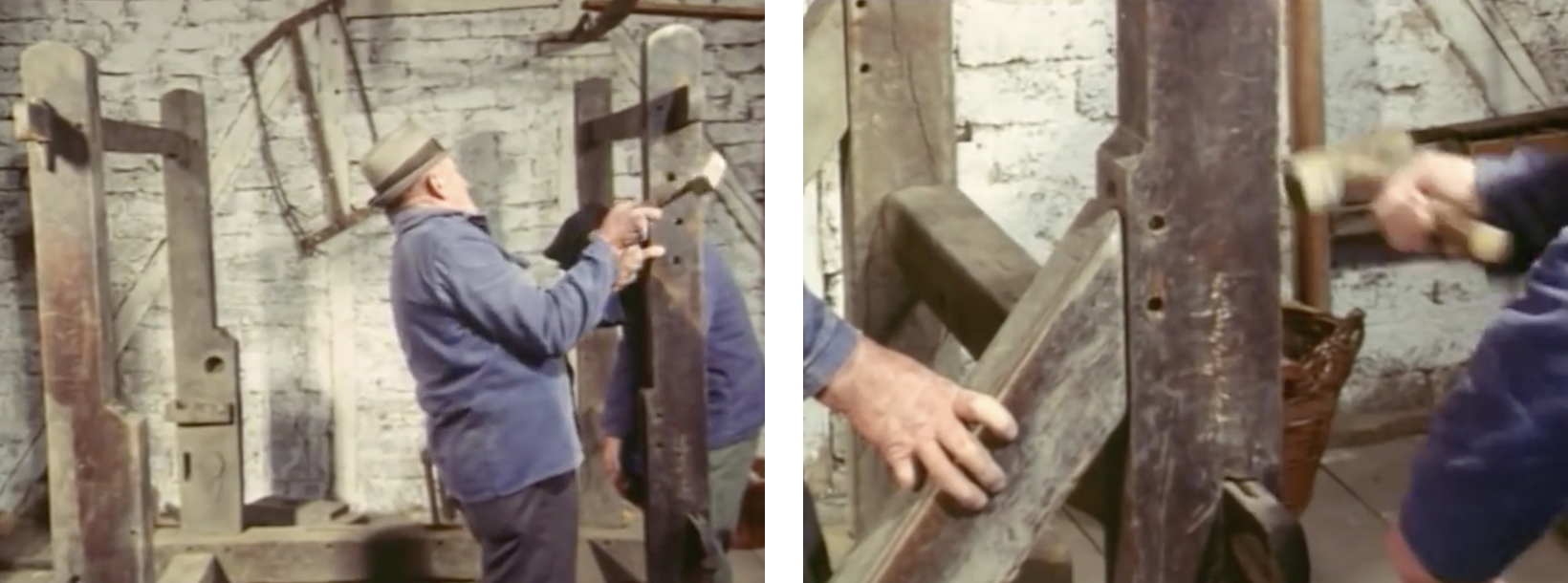

Wilhelm Mosel and Otto Klos, who are demonstrating setting up the loom here, first assemble the base of the frame, or Zarich. As with a half-timbered house frame, they connect the individual parts and knock them together with a hammer.

As soon as the base structure is in place, the corner posts are inserted.

The two men are experienced linen weavers. For the film they are setting up this hundred-year-old loom one more time. They brace the posts at the top with crosspieces.

Handlooms were usually made of oak. In the old days, simple wooden items like this were usually tailor-made by village carpenters. The carpenter took the weaver’s height and his domestic space into consideration, so every old hand loom is unique.

The men use only wooden nails and pegs to secure the wooden parts of the frame.

In the Moselle and Hunsrück areas some looms were richly decorated with carvings. They were probably made by specialized craftsmen.

The rear posts are set up in the same way as the front.

The loom frames suffered little wear and tear and were passed from generation to generation. Many families owned their own loom, which they used to weave linen for their own use or partly for sale. When domestic linen weaving was finally abandoned after the Second World War, the looms and other equipment such as winding gear and spinning wheels were thrown away, burned or at best stored in a corner of the attic. As a result, knowledge of the old techniques of linen weaving was largely lost.

You can clearly see the peg holes into which the wooden pegs will be hammered.

Now the men pick up the cloth beam on which the finished fabric will be wound during weaving. Years of experience and dexterity are needed to find the right parts in the pile of wood and put them together quickly. All the pieces must fit snugly together to prevent the cloth from twisting out of shape later on in the weaving.

For weavers who made a living from linen weaving, the loom had a permanent place rather than being re-assembled every winter. Sometimes, these looms were anchored to the floor or the ceiling beams to stop them vibrating or slipping when the loom was beaten hard.

The loom being constructed here is a so-called full loom (Vollwebstuhl), with corner posts connected at the top with crosspieces. This type was common in the Eifel and Hunsrück regions.

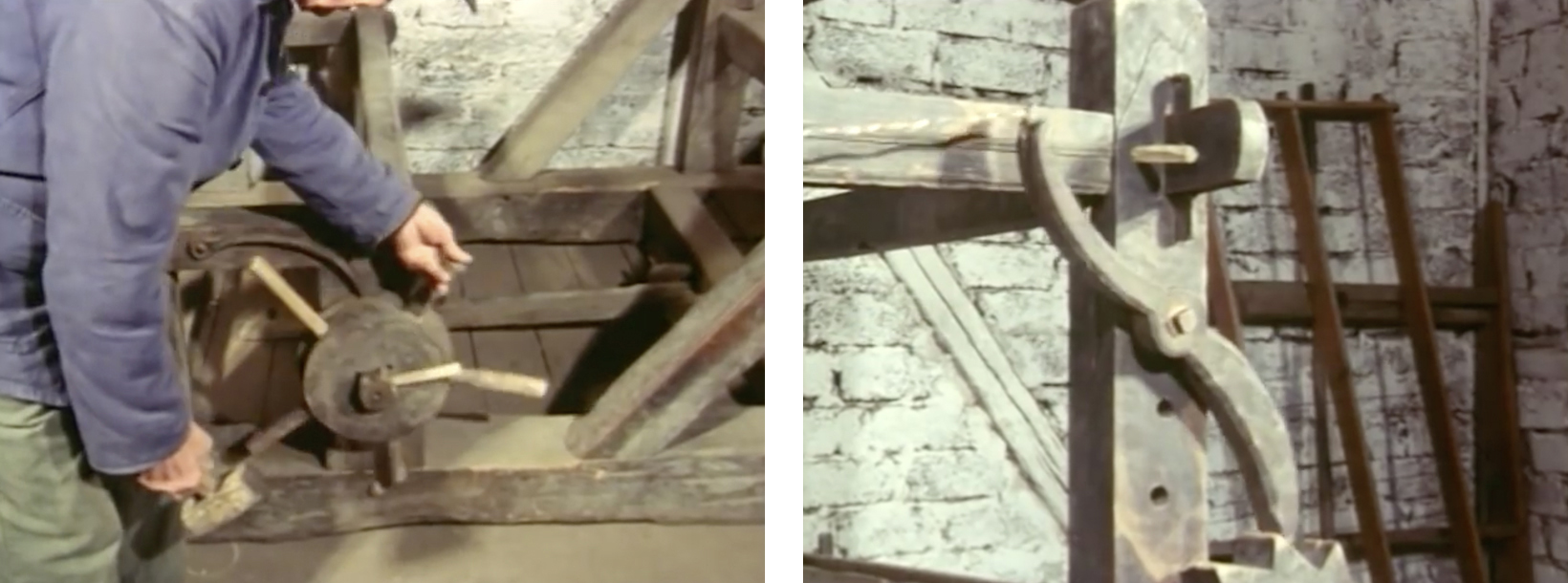

Wilhem Mosel knocks off the protruding wooden pegs to avoid damage or injury while working.

The men push the loom to its final location. The frame is now 1.92m long, 1.39m wide and 1.89m high. It can weave a cloth up to 1.10m wide. Wilhelm Mosel attaches the brackets for the cross sticks.

The round cloth beam is inserted, then the crossbar called the knee beam. Wilhelm Mosel fastens the two treadles to the loom frame with an iron bar. These will later be used to pull down the two leaves, one after the other.

Now they must fit the brackets for the warp beam. The sturdy, rotating warp beam has a slot along its length. This is where the stick at the end of the warp will be inserted later. The men fasten a wooden ratchet wheel (das Garerad), to the warp beam. With the help of a locking mechanism this allows the weaver to unwind the warp gradually.

The weaver can also wind the cloth beam, using a wheel with wooden handles. The cloth beam is also fitted with an iron ratchet wheel, fixed with a pawl, so that the warp can be tightened later on. The large wooden pawl (Der Fäller) prevents the rotation of the ratchet wheel. The weaver can later release the lock with a cord without having to get up from work.

Now Wilhel Mosel inserts the seat board. Meanwhile, Otto Klos whittles some small sticks. They will later be used to attach the end of the warp to the warp beam.

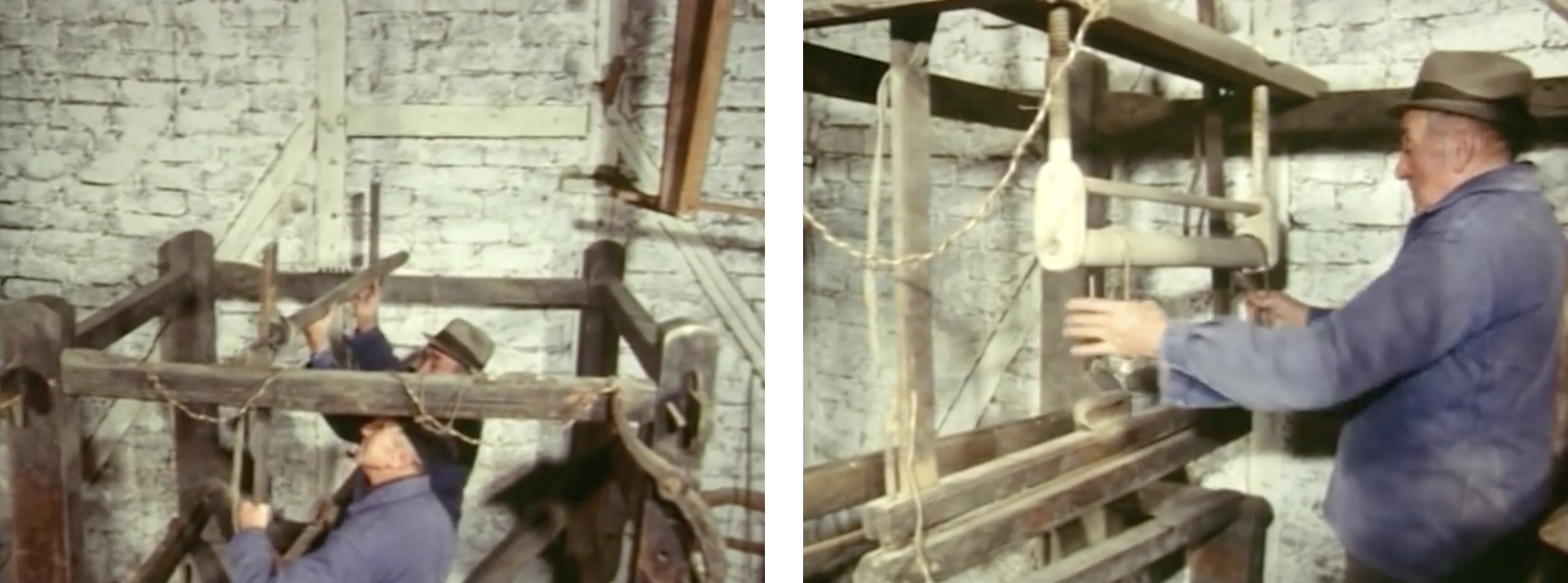

The men can now hang the batten or lay (2). This is hung from the wooden loom frame so that it moves like a swing. In a similar way they also hang the pulley mechanism for the shafts. This has two leather straps on which the shafts are hung so they can be pulled down one after the other during weaving.

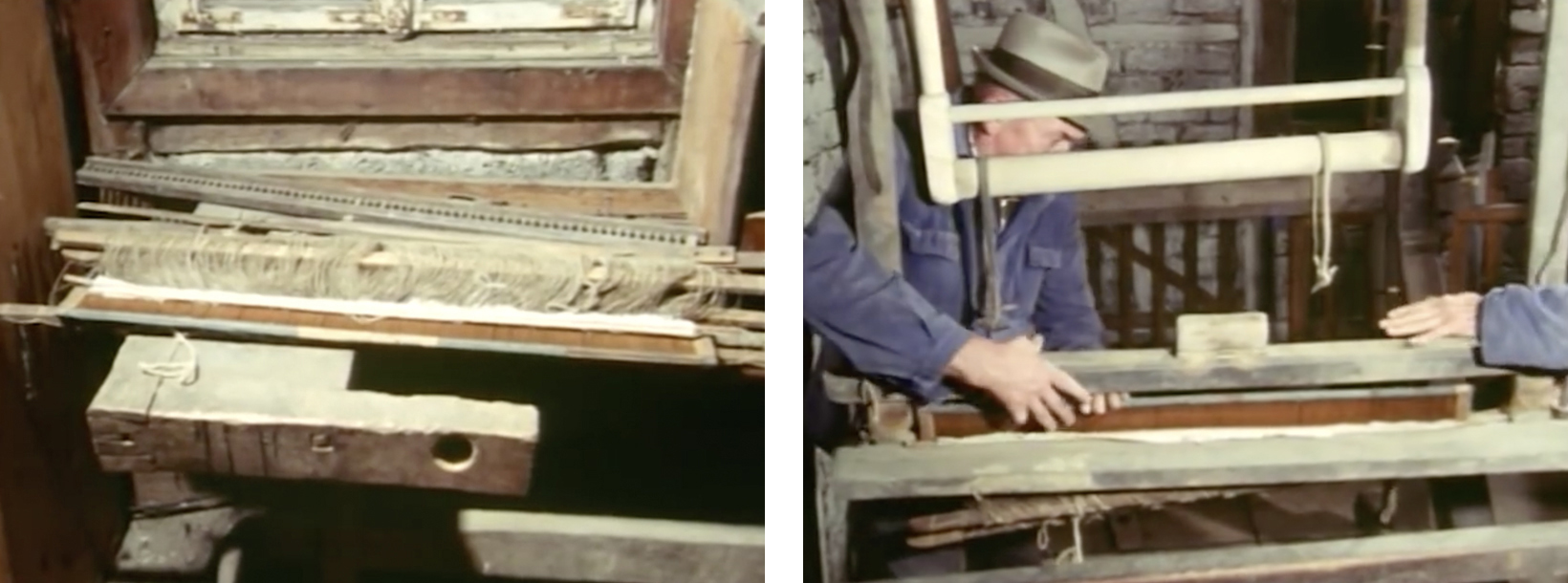

Now they can install the gear (das Geschirr)(3). This consists of the reed and the two shafts. The comb-like reed is inserted into the lay. The weaver uses it to beat each weft thread firmly onto the fabric. As the name suggests, reeds used to be made from the stems of the plant. In the 19th century, however, this was replaced by stronger metal wire. The heddles are made of string with small metal eyes in the middle through which the warp threads are drawn. The remnant of the last cloth woven on the loom is still hanging in the heddles. This makes it easier to attach the new warp later.

The gear was subjected to heavy use during weaving. Unlike the robust loom frame it had to be repaired or replaced more frequently. Professional reed makers were once common in the Lower Rhine area. Reeds were also sold at markets or by itinerant traders in the mountains.

The weaver now connects the two leaves with the treadles. The loom is now functional.

Notes:

- Martini in the original: St. Martin’s Day or Old Halloween, 11th November.

- The german text gives two alternative terms to designate the pivoted frame holding the reed: die weblade and die Lad. Luther Hooper and John Tovey use Batten, while Lay is used by John Duncan in Practical & Descriptive Essays on the Art of Weaving (1808).

- The German term das Gerchirr, which my dictionary translates as dishes, is used here to refer to the combination of reed, heddles and heddle bars. I have translated this with the word gear, sometimes used by weavers as an alternative to harness in referring to the entire shedding mechanism.