(March 2022)

The following is a transcription of the film Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 3: Aufbäumen, Anknüpfen und Schlichten der Kette, with my translation of the original German commentary presented alongside stills from the corresponding scenes in the film.

The film is the third in a series recording the re-enactment of traditional linen weaving in the town of Dickenshied in 1978/9, produced by Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

All images courtesy of Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

Watch the original film here. For more information about the films read this.

Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 3: Aufbäumen, Anknüpfen und Schlichten der Kette

Rural Linen Weaving in Germany: 3: Beaming, Tying and Dressing the Warp

Commentary

It is winter in the Hunsrück region. On the farm, this is the time when linen weaving can begin. Meanwhile in Dickenschied the old hand loom has been assembled.

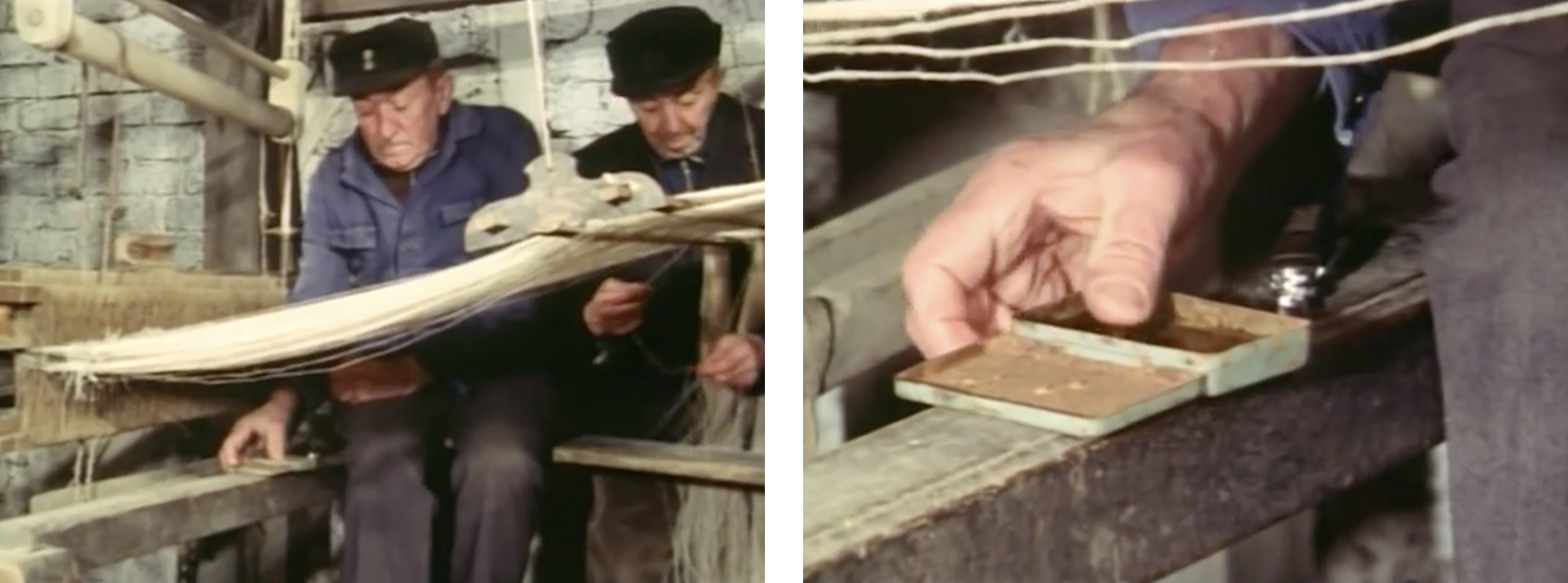

For Wilhelm Mosel and Otto Klos, who are re-enacting the preparatory stages of linen weaving for the film, the most complex phase of linen production now begins. The warp must be mounted – stretched out, in other words – on the loom. This requires some helpers. Sometimes several families would help each other.

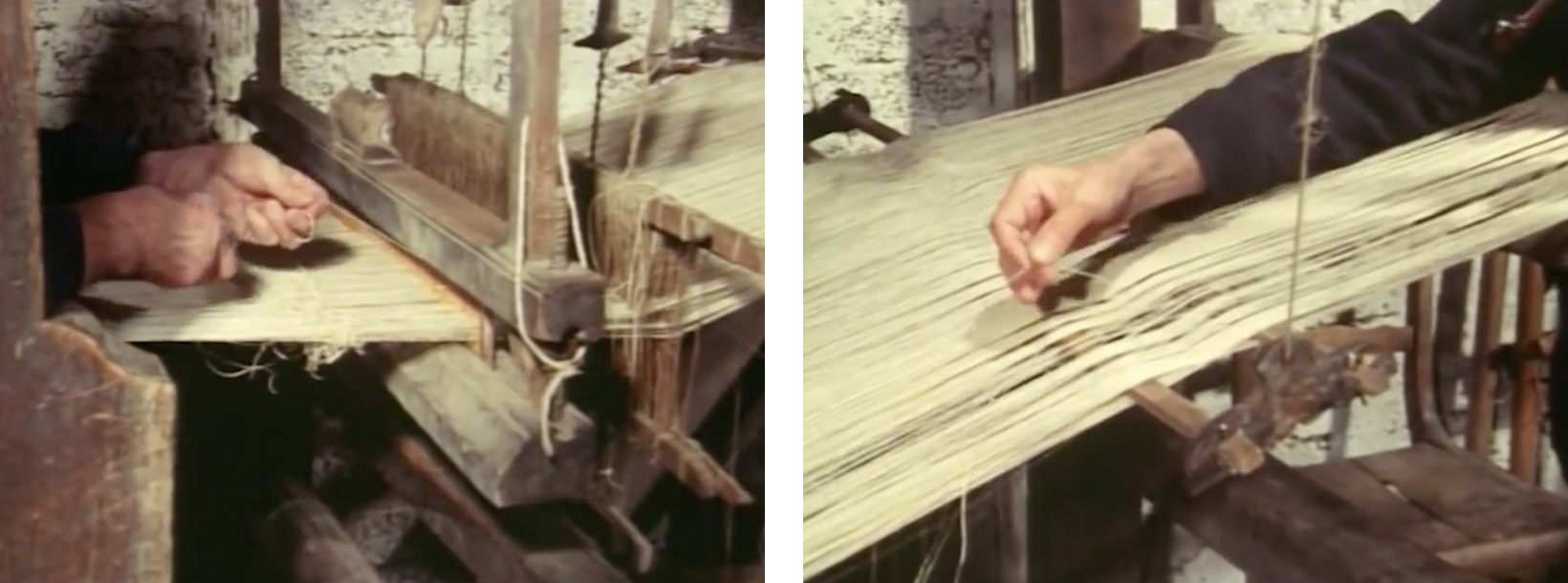

A willow stick is pushed into the end of the warp. The men attach the stick to the warp beam.

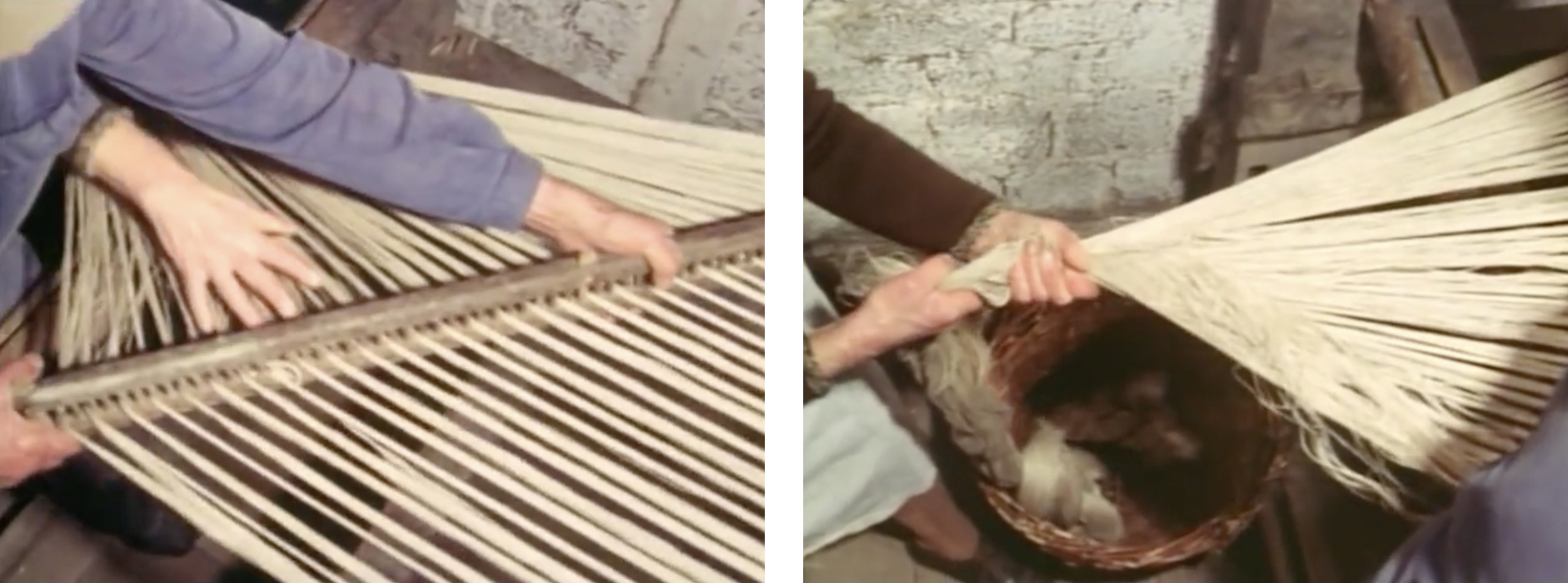

Now the individual gangs (1)– the groups of 40 threads made during warping – are evenly spread out.

Frau Klos, who is helping with the set up, stands at the front of the loom and makes sure to pull the warp evenly taut. Wilhelm Mosel uses the raddle (den Scheid). This serves to keep the warp regularly spaced when winding it on.

Each gang is inserted in the space between the wooden teeth of the raddle. The men must make sure that the gangs do not cross but lie evenly next to each other. Crossing just a few threads could lead to weaving errors, so great care is needed.

Once the last gang is placed, the men put the cap on the raddle to stop the yarn from slipping out. Wilhelm Mosel also fastens the cap to the raddle with wooden dowels.

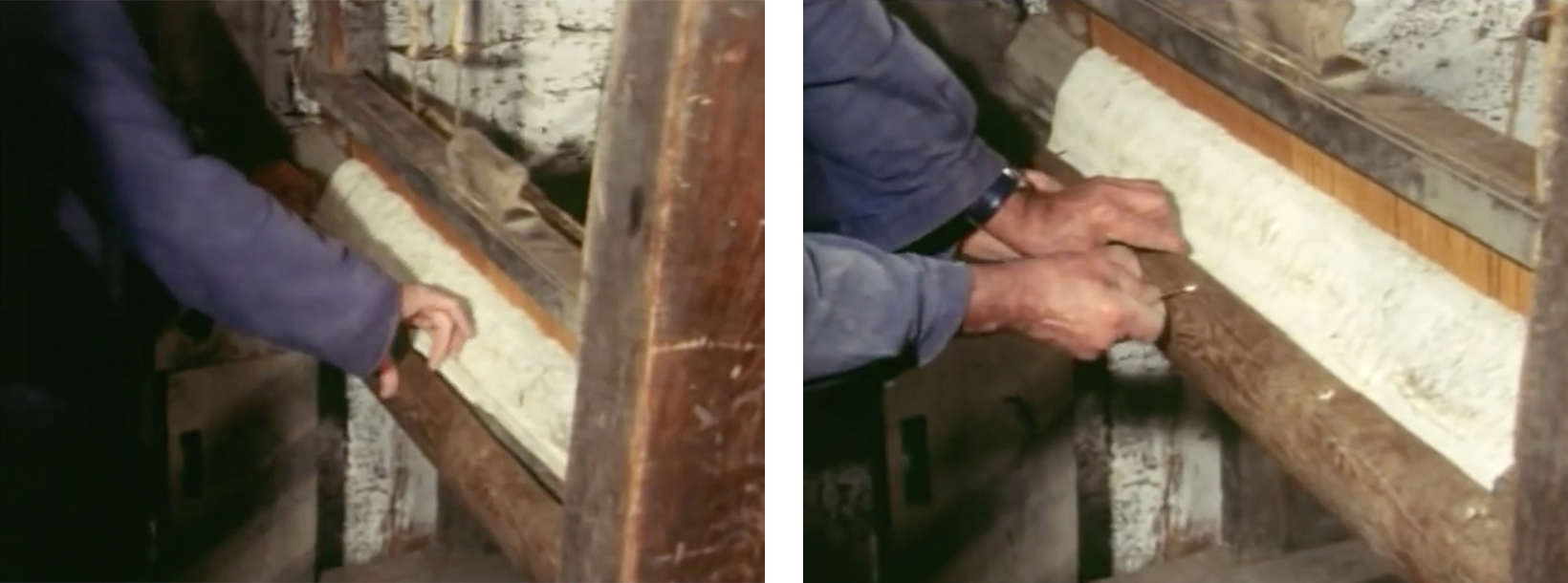

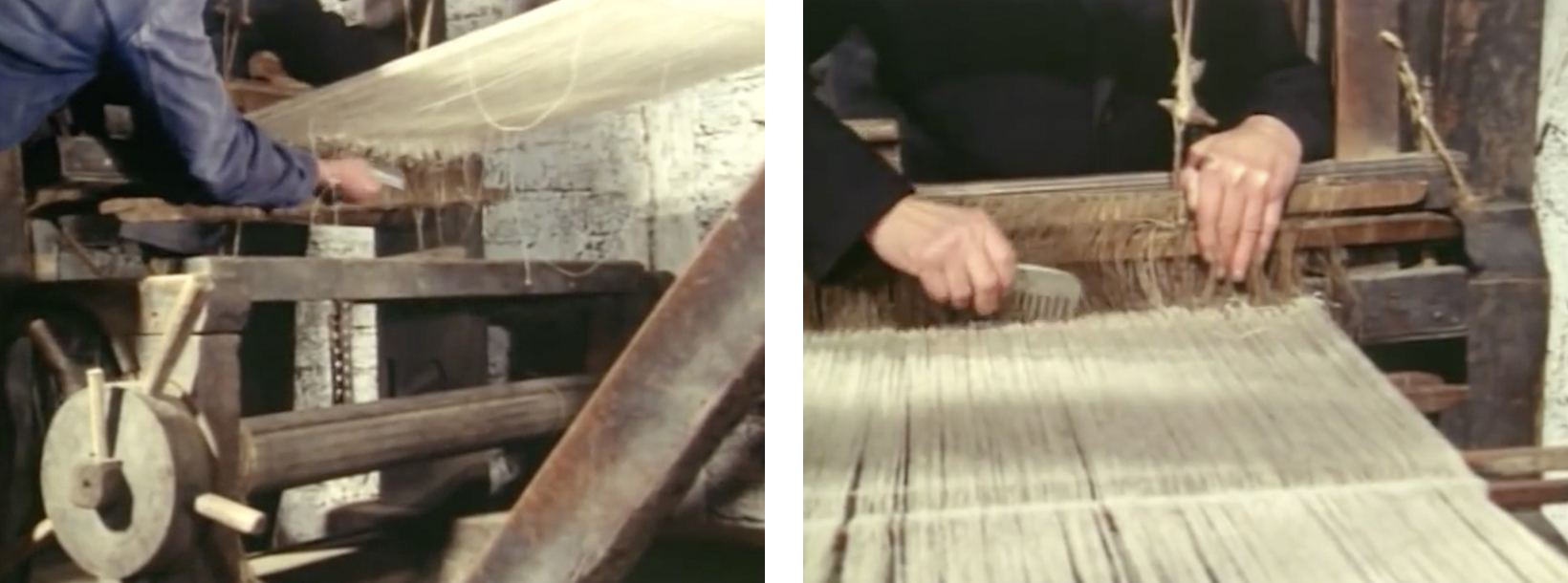

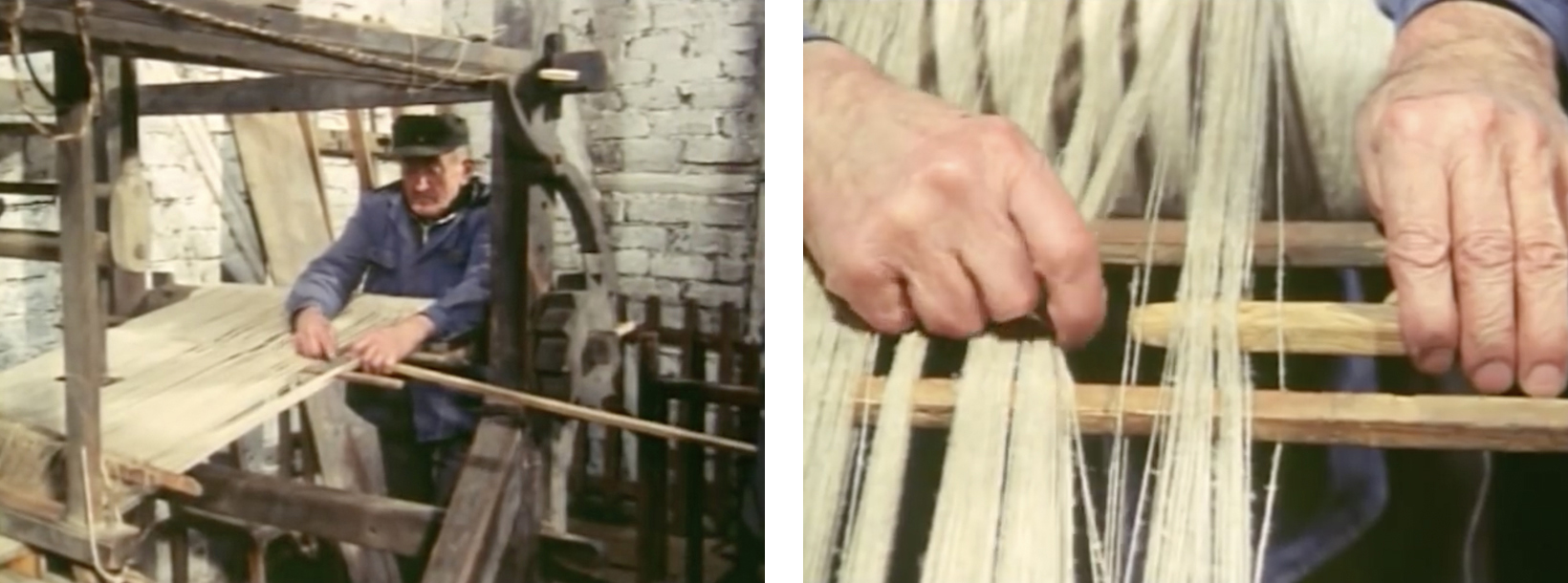

Now they can start winding the warp onto the warp beam.

The two helpers slowly turn the beam with two levers inserted through it. At the same time, the weaver holds the raddle with the gangs running through it. The tension in the yarn means they have to work hard to turn the warp beam.

Wilhelm Mosel holds the raddle straight in the warp so that the layers of yarn are evenly distributed on the beam as it is wound on. Frau Klos ensures that the threads are pulled tight. She repeatedly reaches into the yarn with her hand to organize it. In order to ensure an even tension of the thread and a firm winding, she must pull on the warp with all her strength. In this way, the chained warp gradually loosens.

Frau Klos inserts a cord into the loop at the beginning of the warp. This way she can keep pulling until the yarn is almost completely wound onto the beam. Wilhelm Mosel ties the cord from the end of the warp to the breast beam.

The weaver first puts one and then a second stick through the cross that was created when the warp was made. In this way, the yarn is divided into two equal halves, alternating between threads on the bottom and threads on the top. The cross sticks are attached to brackets hung from the loom. They will remain in the warp while it is mounted on the loom, and also later during the weaving.

They must make sure the workshop is kept at a constant temperature and humidity, since the threads can stretch or shorten if this varies.

The men take out the raddle, which is no longer needed.

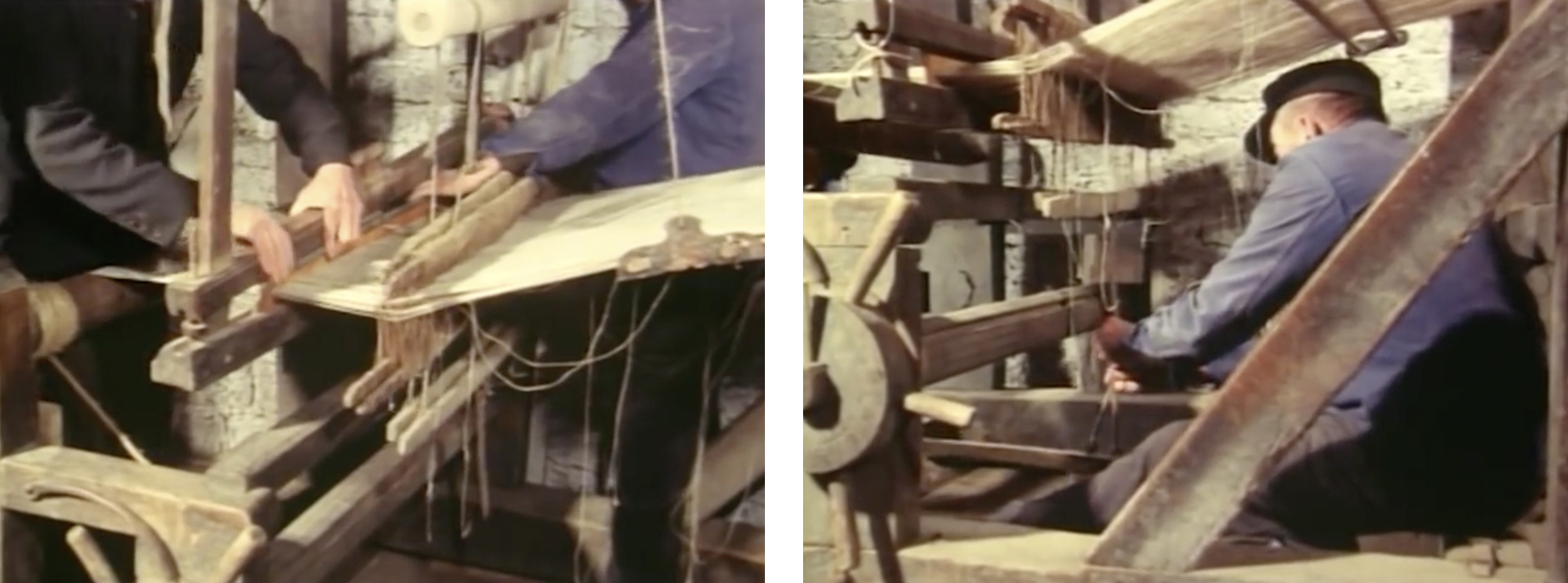

Now the men can start tying the threads. To do this, Wilhelm Mosel and his helper first have to re-hang the lay (2), along with the reed and heddles.

The remnant of the old warp, cut away from the last cloth to have been woven, remains in the heddles. This makes it easier to mount the new warp.

The men insert the reed into the lay.

Wilhelm Mosel hangs the harness pulley mechanism on the loom frame, as he did with the lay.

The weaver and his helper now attach the shafts to leather loops.

In order to make room in the loom for tying-on, the men have to temporarily push the lay and harness forward.

When the last piece of cloth was woven, a willow stick was sewn into the end of it. The stick, with the remnant of the old warp, known as the thrum (3) (German Thumm), is now inserted into the slot in the breast beam and fastened with wooden pins.

Now the weaver checks that the loom is level and square. A skewed or leaning loom frame can lead to distortions in the woven cloth. A slight difference in the posts or an unevenness in the floor can cause this.

The loom is now level.

Wilhelm Mosel hangs the lamms from the shafts. These will later be connected to the treadles to allow the shafts to be pulled down vertically.

The gangs of the old warp remnant are looped together on the back of the heddles. The weaver now undoes them. As with the new warp, each gang contains 40 threads – a total of 1440 threads that need to be tied to the new warp.

After Wilhelm Mosel has untied the cord from the end of the new warp, he cuts open the loops of yarn. He must be careful not to tangle or cross the threads too much.

The weaver also pulls out the cord that was threaded in the cross when the warp was made. The cord has now been replaced by the two cross sticks and is no longer needed.

Otto Klos unwinds some yarn from the warp beam to lengthen the warp in the work area.

Now the individual gangs of the new warp must be sorted on the cross sticks. This is necessary to avoid crossing threads when tying-on. The men pay very close attention to the correct order of the yarn.

The yarn is now straight and organised on the cross sticks.

Now the men measure the length of the warp threads on the left and right edges. The length should be the same. Threads that are too long will be cut when tying-on. Otto Klos locks the warp beam so that the warp does not unwind when tying-on.

The tie-on that follows is a tedious, time-consuming job.

First, Wilhel Mosel shortens the new warp threads to the right length.

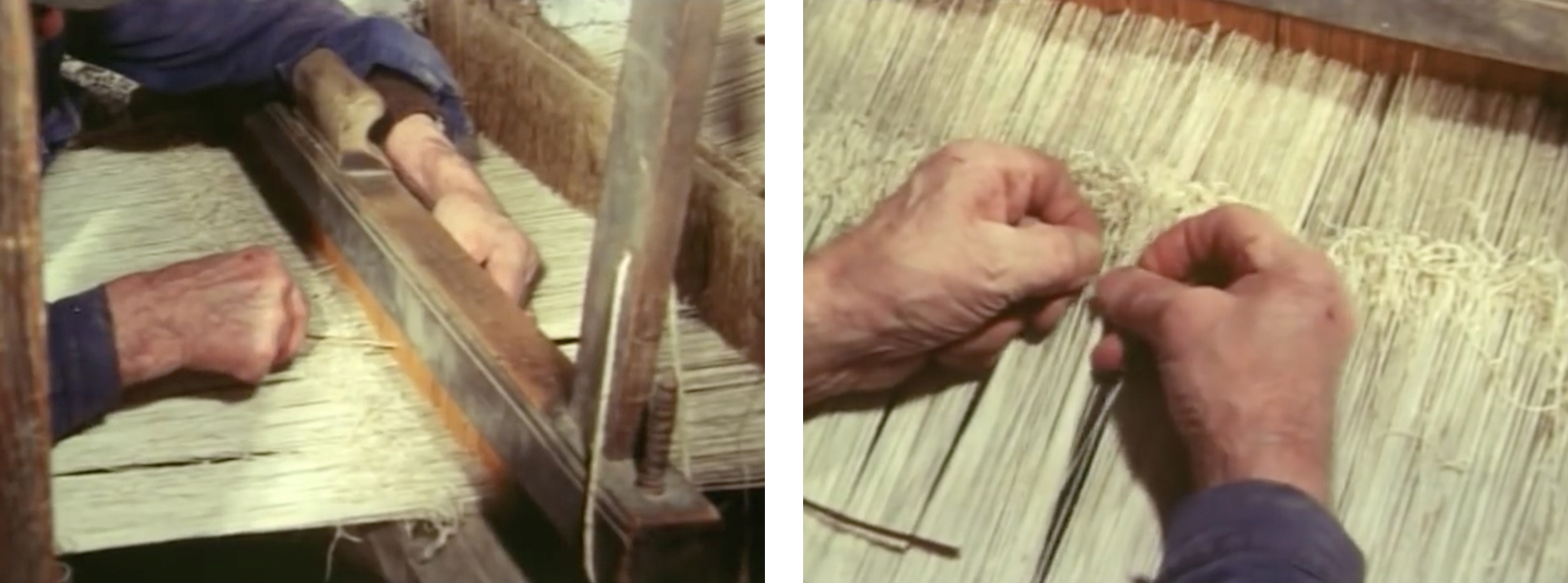

He cuts open the loops of the old warp ends.

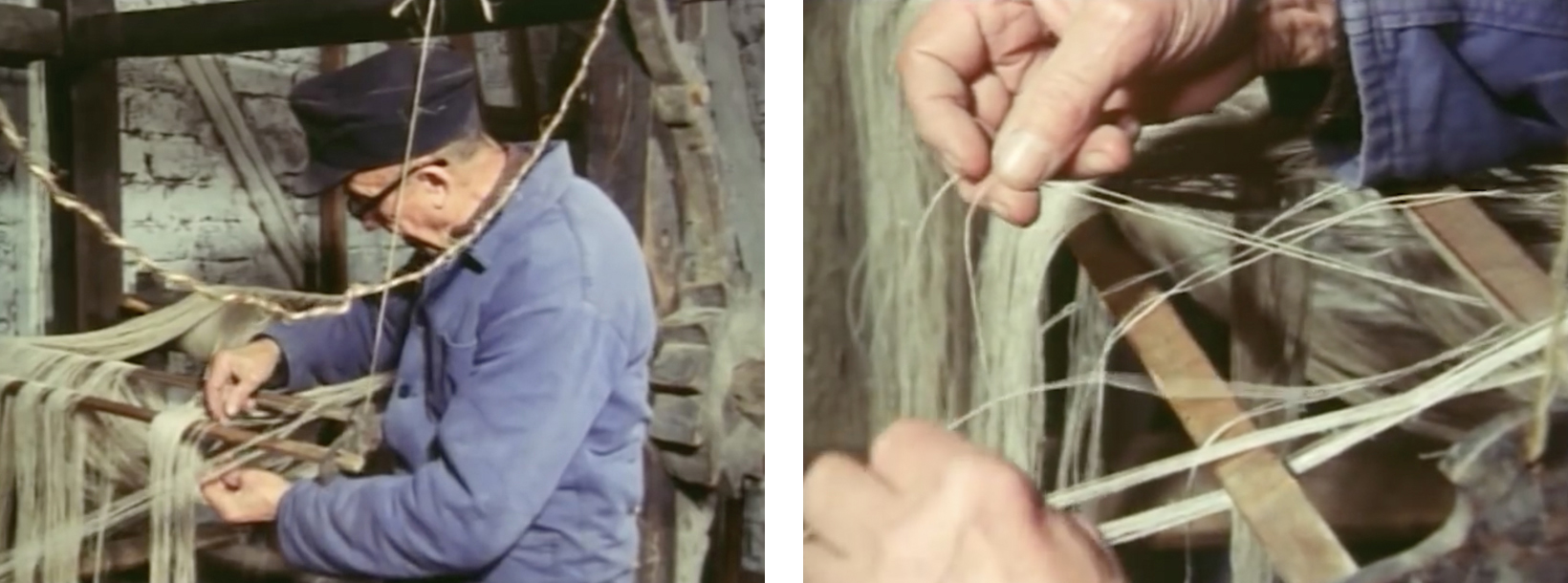

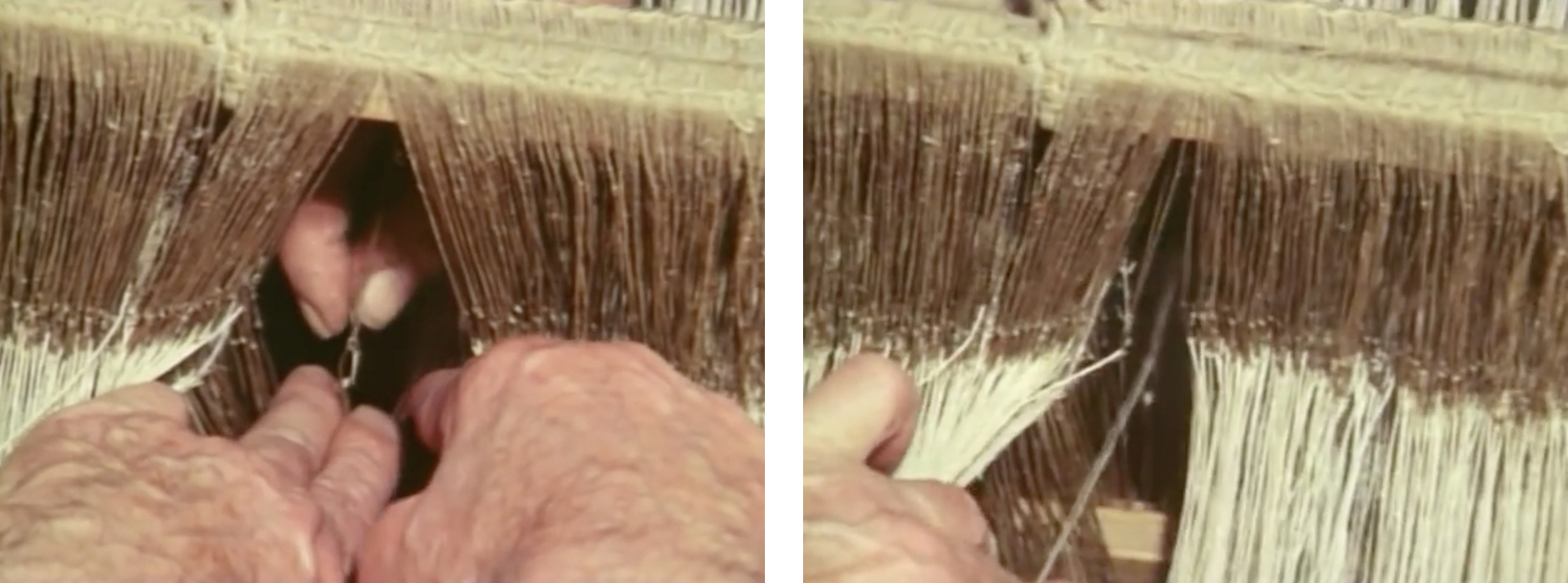

Now each thread of the old warp must be tied to a thread of the new warp in the correct order. This requires good dexterity and a high level of concentration.

In commercial weaving it was sometimes the case that the weaver would not to do this himself, a task which sometimes took several days, but have it done by skilled young women for a fee. The farmers who wove for their own use usually tied the warp themselves.

The assistant sorts the threads into pairs before tying them on, as this makes it easier to spot mistakes.

A pair of two threads are called Kameraden (comrades), a single thread Kamerad. In the harness, the threads run alternately through one shaft and then the other. In weaving this creates the typical tabby weave, with alternately intersecting yarns.

Wilhelm Mosel twists the individual ends. To tie them, he forms a loop and then tightens it.

Leaving the remnant of the old warp in the harness makes the weaver’s work considerably easier. Without this, the threads of the new warp would have to be laboriously pulled through the eyes of the heddles and then through the reed. That takes a lot more time than tying-on.

After a few hours, the men have already tied-on half the threads. The space in the loom is getting tighter and tighter.

The knots that Wilhelm Mosel makes must be as small as possible so that they can be pulled easily through the heddles. There is a risk of thread breakage if they get stuck.

The linen yarn used for the warp was mostly spun on spinning wheels by women on long winter evenings.

In order to make a nice fabric, the yarn must be spun with as uniform a thickness as possible. Unevenness in the warp yarn can lead to thread breakage during weaving.

The knotting of the warp was particularly difficult for older weavers. Their eyes would tire quickly and sitting in a hunched posture for long periods would be painful.

The weaver frequently moistens his fingers with fat in order to twist the threads better.

Sometimes the corresponding Kameraden have to be found because the threads within a gang are not always in the right order.

Wilhelm Mosel cuts open another loop of the old warp with a knife.

It should not get too cold in the weaving room, because knotting is much slower with cold and stiff fingers. Nevertheless, the stove must not be too hot, otherwise changes to the humidity could affect the yarn.

The next day: Wilhelm Mosel and Otto Klos have almost finished tying-on the warp. It will soon become clear if any threads have been missed and if the ends have been joined in the correct order. This laborious work, which can last several days depending on the number of warp threads, is almost complete.

The knots and thread ends are clearly visible. They are still in front of the harness and have yet to be pulled through the heddles and the reed.

When the tying is finished, it turns out that there are two threads left on the old warp. The men add a thread to the new warp by attaching a spool.

The spool will remain behind the loom during weaving and gradually unwind.

Now the knots have to be pulled through the heddles.

First, Wilhelm Mosel connects the breast beam to the cloth beam with a cord. Turning the wheel on the cloth beam also moves the breast beam, and thus enables the weaver to tension the loose warp.

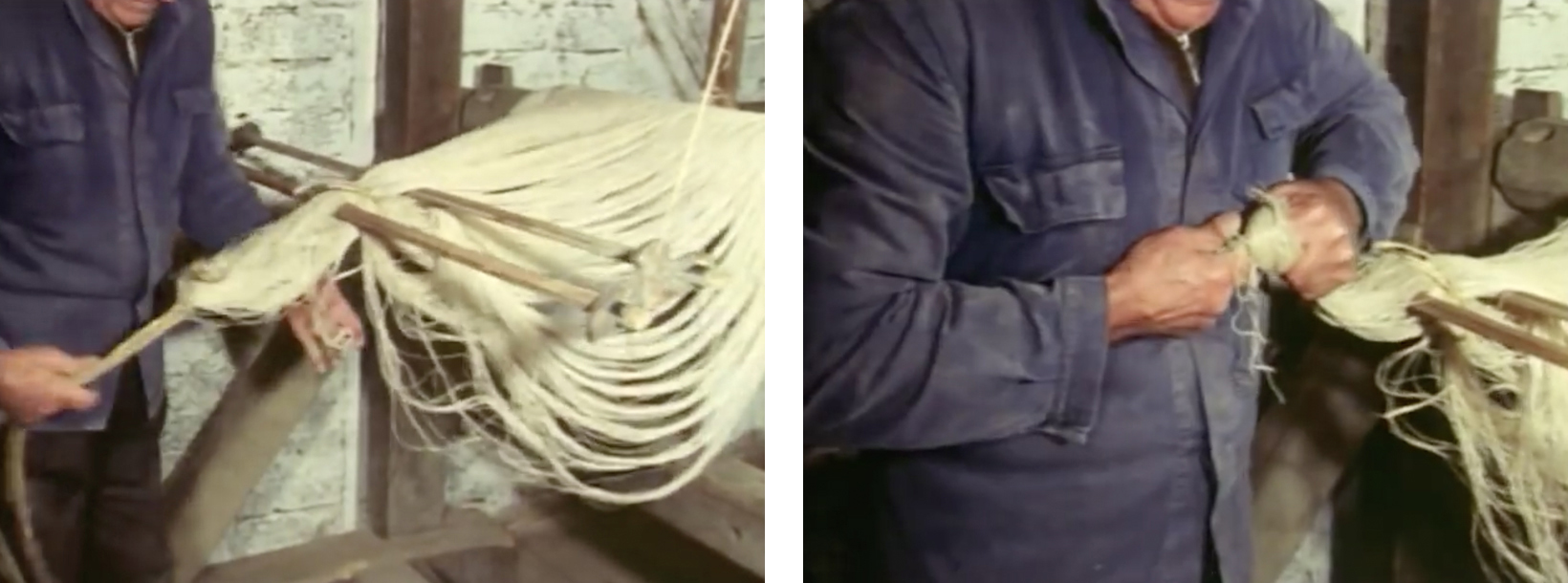

Wilhelm Mosel and Otto Klos use horse combs to smooth out the loose ends so that they can be pulled more easily through the eyes of the heddles.

The men now begin the draw-through (Durchschaffen). First one shaft and then the other must be very carefully pulled backwards over the row of knots. This drawing-through requires skill to minimise thread breakage.

The eye of each heddle in the harness slides over a knot. This will test how well the warp has been knotted. There is also a risk of damaging the heddles when doing this.

Up until the beginning of the 20th century it was common in many places in the hills, such as here in the Hunsrück, for people to make their own household linen. But by no means every household had its own loom. Many families spun yarn themselves but had it processed by a weaver, most of whom worked on a part-time basis.

With the advent of machine looms, cheaper cotton fabrics increasingly replaced unprofitable linen. It was mostly older weavers who continued with traditional linen making and tried to earn a living from it, being either unwilling or unable to change jobs.

The harness can now be placed back in the middle of the loom.

The men take the reed out of the lay to get the knots through the it more easily.

They move the reed up and down as they pull it along. This makes it easier for the knots to slide through.

The lay is moved back and the reed is reinserted.

Wilhelm Mosel now climbs into the loom to connect the treadles to the shafts.

Despite all the care taken when drawing-through, some warp threads have broken. They now need to be re-tied.

Unlike the previous tying, the yarn must now be threaded through the metal eyes of the heddles and then also through the reed.

Wilhelm Mosel re-ties it in front of the lay to the corresponding thread of the old warp remnant.

Because the warp yarn is arranged evenly on the lease rods, the assistant can more easily find the corresponding Kameraden.

The weaver pulls the threads through the heddles and reed with a threading hook, which is slightly bent at the end like a crochet hook.

The actual weaving of simple linen fabrics did not require a great deal of knowledge, unlike the warping and tying-on, so many farmers had this preparatory work done partly or wholly by specialists.

While the men in the workshop are busy tying the threads, Frau Klos is preparing the dressing (4) in the kitchen. This is a flour paste for coating the warp. This makes the yarn smoother and more durable and prevents it being damaged through contact with the heddles.

In the hill country, such as here on the Hunsrück, inexpensive rye flour was used for the dressing. It is mixed with water to a paste that is not too thick. Wheat or buckwheat flour was more commonly used on the Lower Rhine. Sometimes dressing was made from potato or chestnut flour.

After Frau Klos has mixed the flour with cold water, she adds hot water and stirs the dressing until the lumps have dissolved.

Linen and cotton warps were dressed in this way. Wool yarns had to be sized with glue. Oil or lard was also used in the dressing of cotton. In the case of linen, the addition of fat was usually dispensed with since it was difficult to remove from the finished fabric with the usual bleaching and washing processes.

While Frau Klos was stirring the dressing in the kitchen, the men in the workshop have begun preparing the yarn for dressing. To do this, they insert several additional cross sticks into the warp. Gathering the threads in this way makes the surface of the warp tighter and easier to work with. It also simplifies the sorting and retrieval of individual warp threads when a thread breaks during weaving.

Wilhelm Mosel connects the shafts with the treadles. Now they can test whether or not the shedding works – that is, the alternate raising of the shafts and thus the lifting of half of the warp threads.

The weaver no longer has to laboriously sort the warp to insert the remaining sticks, but can easily push them through the shed.

For dressing, it is necessary to move the harness forward again.

Wilhelm Mosel dips the brushes lightly in the dressing. He must not apply too much dressing, otherwise the linen yarn could stick together.

The leftover dressing will be needed later for weaving.

The damp warp must be left to dry before weaving can begin.

Notes:

- Several alternatives often present themselves when translating the technical terms of weaving. Where appropriate I have used the alternative closest to the German to draw out the shared etymologies. The german word here is Gang. Thus the english gang, rather than portee, to designate a group of threads warped together. Gang is the term used by John Duncan in Practical & Descriptive Essays on the Art of Weaving (1808). It is sill used by some weavers, although portée is perhaps more common.

- The german term used here to designate the pivoted frame holding the reed is Lad, to which lay is closer than batten. Lay is used by Duncan (see note 1 above).

- The term thrumm refers to the individual or collective threads in the warp remnant. In England they used to be sold for making mops etc.

- The German term used here is die Schlichte. I translate this as dressing (made with starch) to make a distinction with size (made with glue).