(August 2022)

The following is a transcription of the documentary film Bäuerliche Leinenweberei 4: Herstellen von Leinwand, with my translation of the original German commentary presented alongside stills from the corresponding scenes in the film.

The film is the fourth in a series recording the re-enactment of traditional linen weaving in the town of Dickenshied in 1978/9, produced by Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

All images courtesy of Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

(Watch the original film here. For more information about the films read this.)

Bäuerliche Leinenweberei: 4: Herstellen von Leinwand

Rural Linen Weaving in Germany: 4: Weaving the Cloth

Commentary

In the Hunsrück region, the cultivation of flax and the weaving of linen were widespread until the beginning of the twentieth century. Here in Dickenschied, near Simmern, linen was woven for domestic use during the winter from Martinmas to Candlemas.

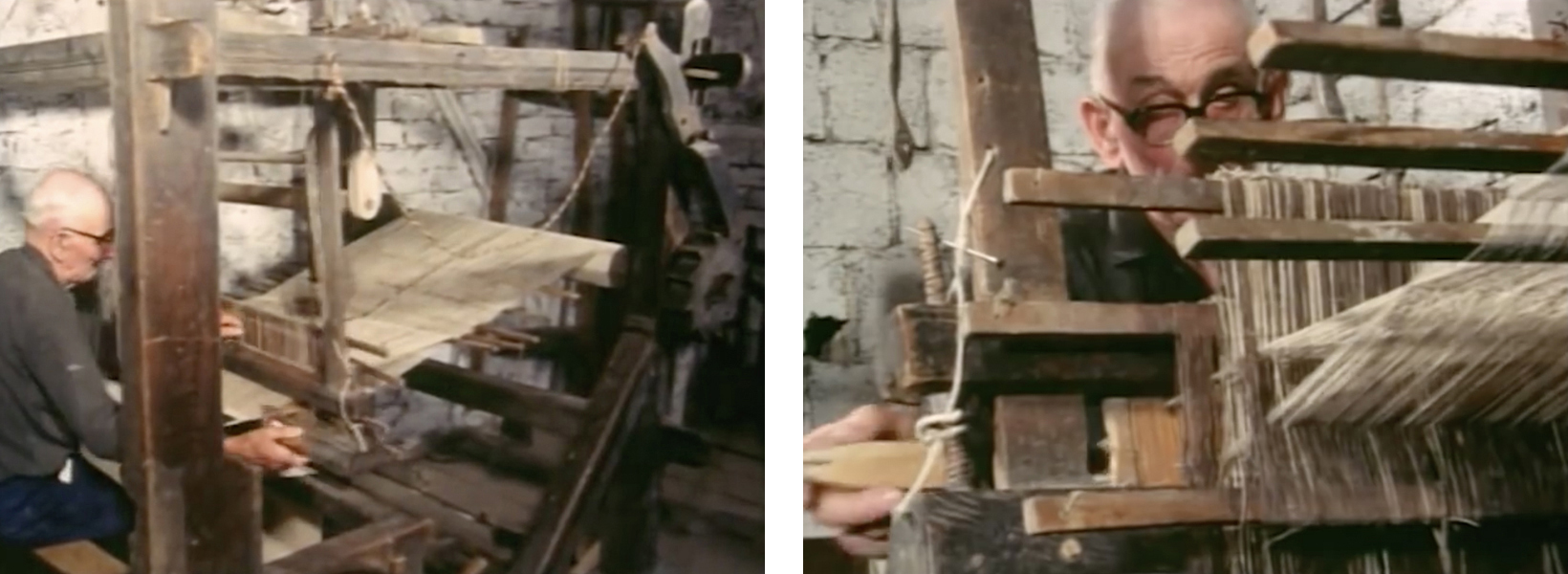

For this documentary film, the manufacture of cloth is being re-enacted in the courtyard of 27 Kirchbergstraße. The nearly forgotten skills of the handloom will be demonstrated by Wilhelm Mosel, accompanied later in the film by Albert Gebert, both of whom used to weave at home.

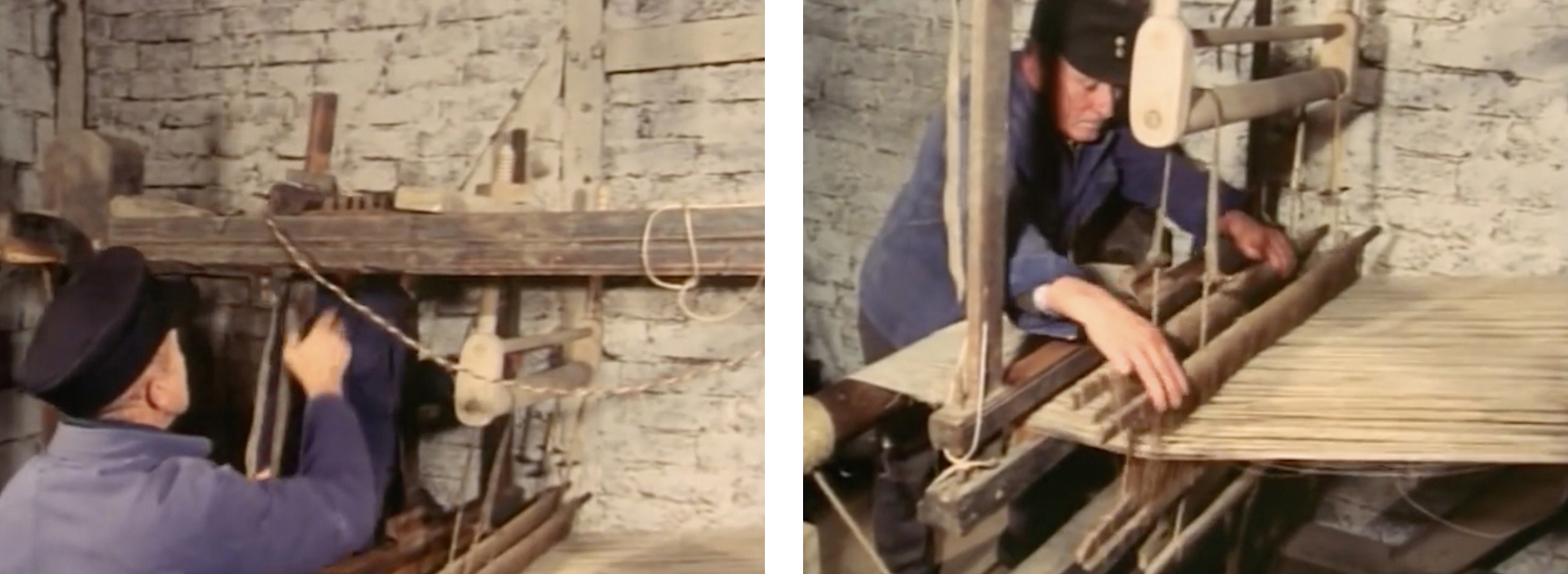

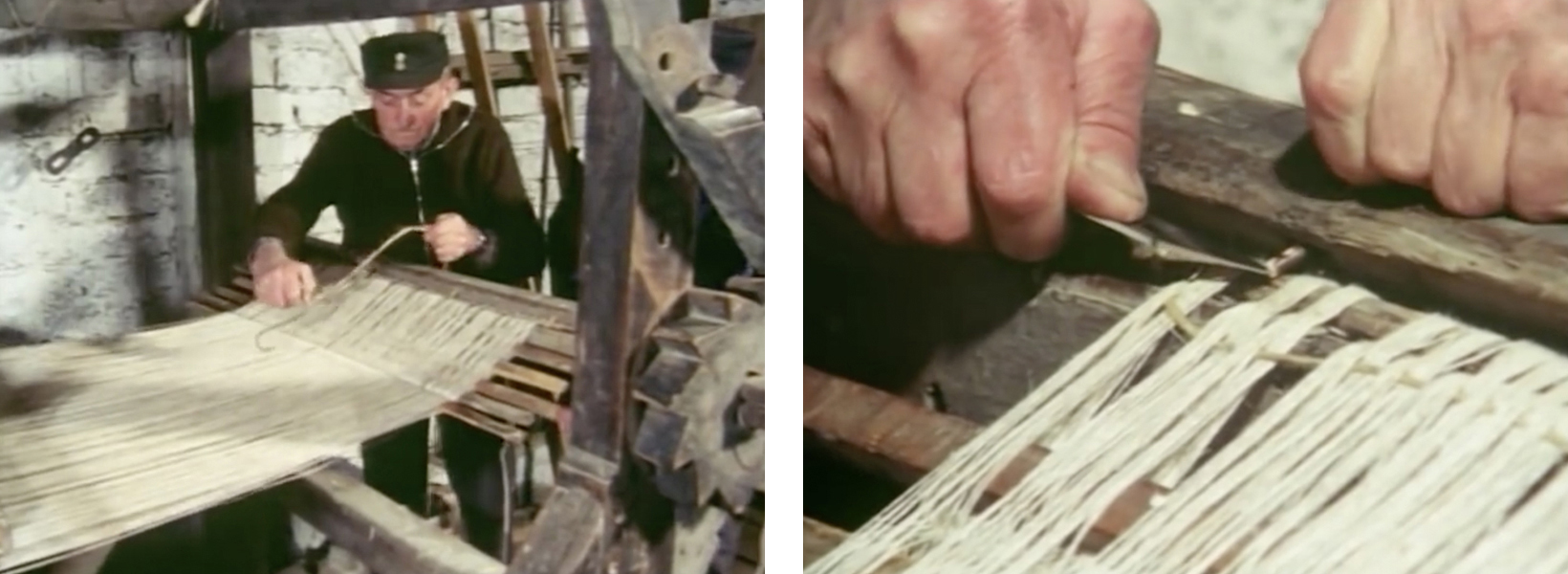

After Wilhelm Mosel and his assistant Otto Klos have wound and stretched the warp, they check the functioning of the loom. To do this, they hang the lay and the harness in their final positions.

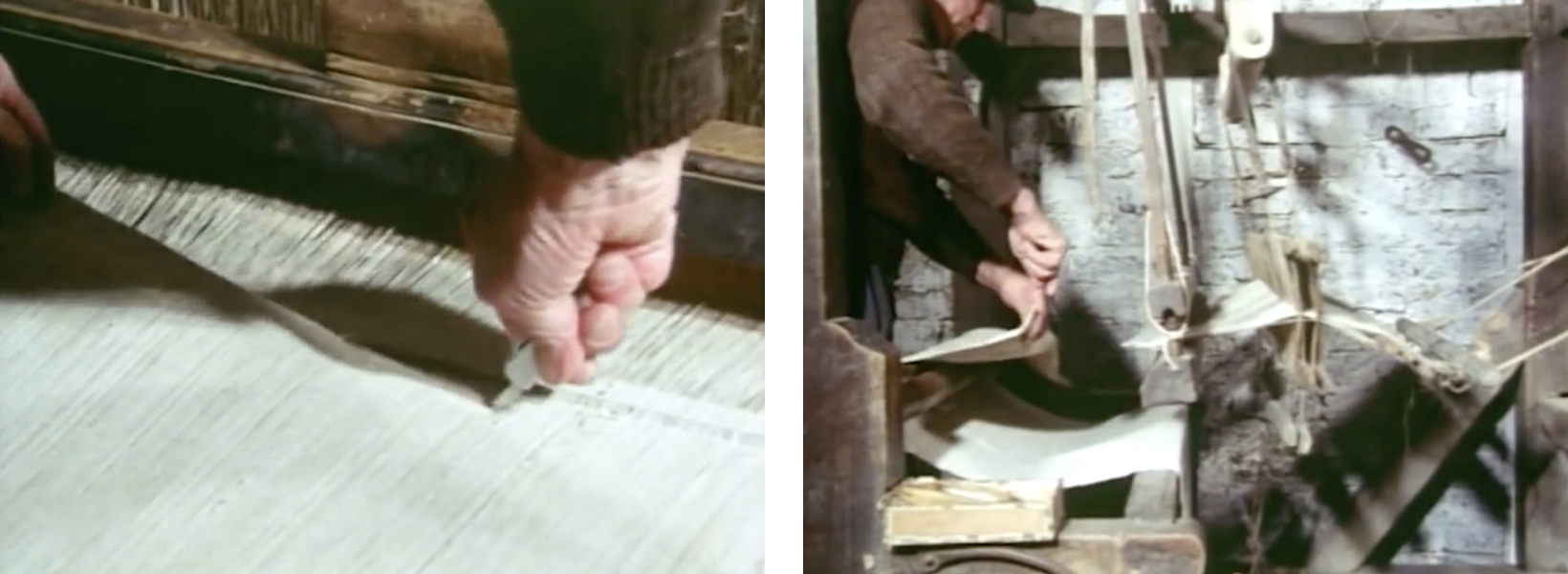

The reed must slide easily over the threads.

When Wilhelm Mosel pulls half of the warp threads up and the other half down, the individual threads must not get caught. It is important that the ‘sheds’ formed in this way open easily so the weft thread can be passed through.

Otto Klos hangs the ‘donkey’ (den Esel), an octagonal wooden weight, on the cross sticks in the middle of the warp. This is also weighted with a horseshoe. This pulls the cross sticks backwards towards the warp beam during weaving.

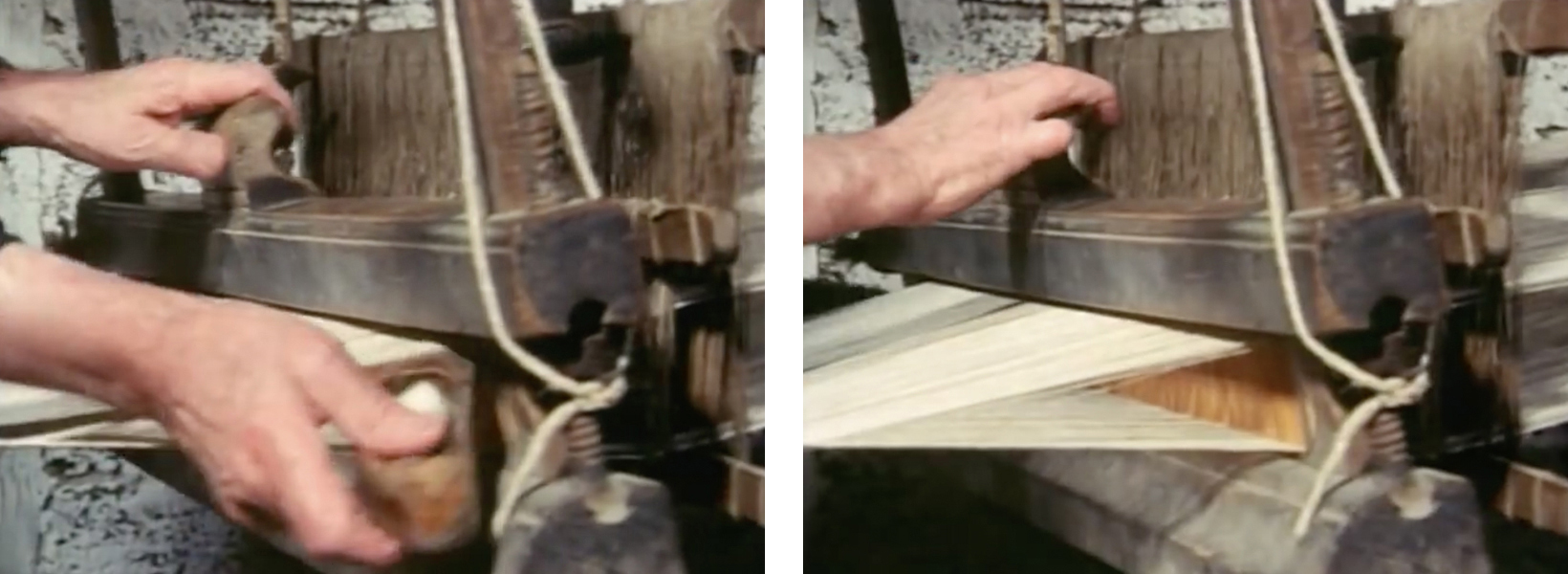

Before Wilhelm Mosel starts weaving, his assistant turns the cloth beam to tighten the warp.

A shuttle and a bobbin with weft yarn are needed for weaving. Wilhelm Mosel now fits the bobbin, made from an elder branch, onto the wicker stick of the little boat-shuttle. The weft yarn is guided through the side opening of the shuttle and unwinds easily as the shuttle slides through the shed.

Now the weaving can start. The weaver throws the shuttle through the shed formed by the shafts and thereby inserts the weft at right angles to the warp. With the lay he beats the weft into the fabric. In this way he checks whether all the parts of the loom are in working order.

A broken thread interrupts the weaving process.

Later, the edge of the fabric will be smoothed out with a flat piece of slotted wood, known in the trade as a ‘Salwend‘. After a few trial throws it is evident that the preparatory work of warping and setting up has been done well.

They are making a typical plain-weave cloth.

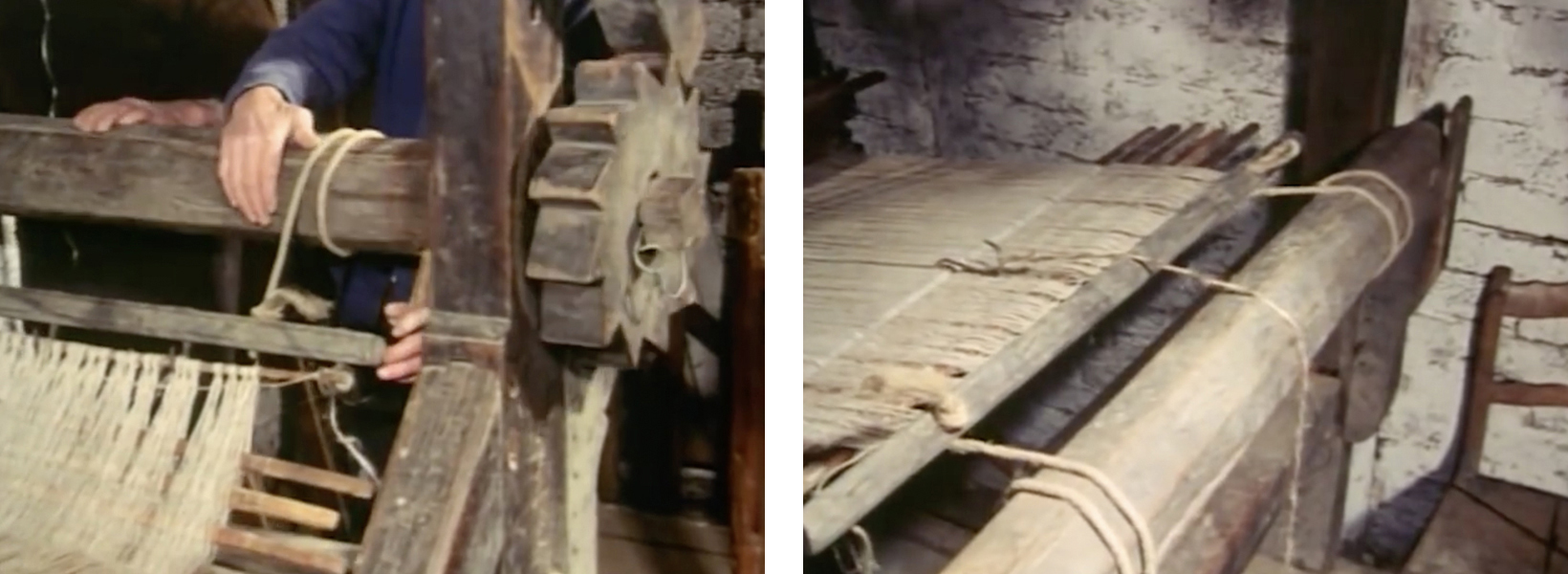

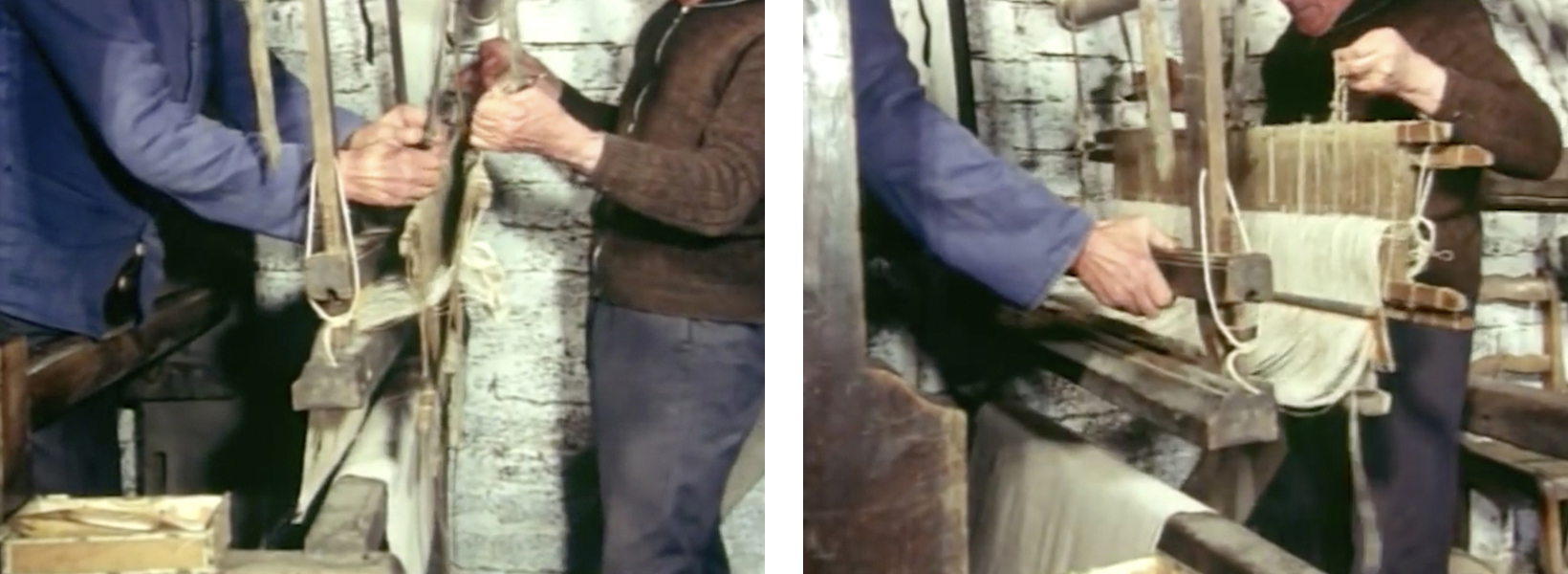

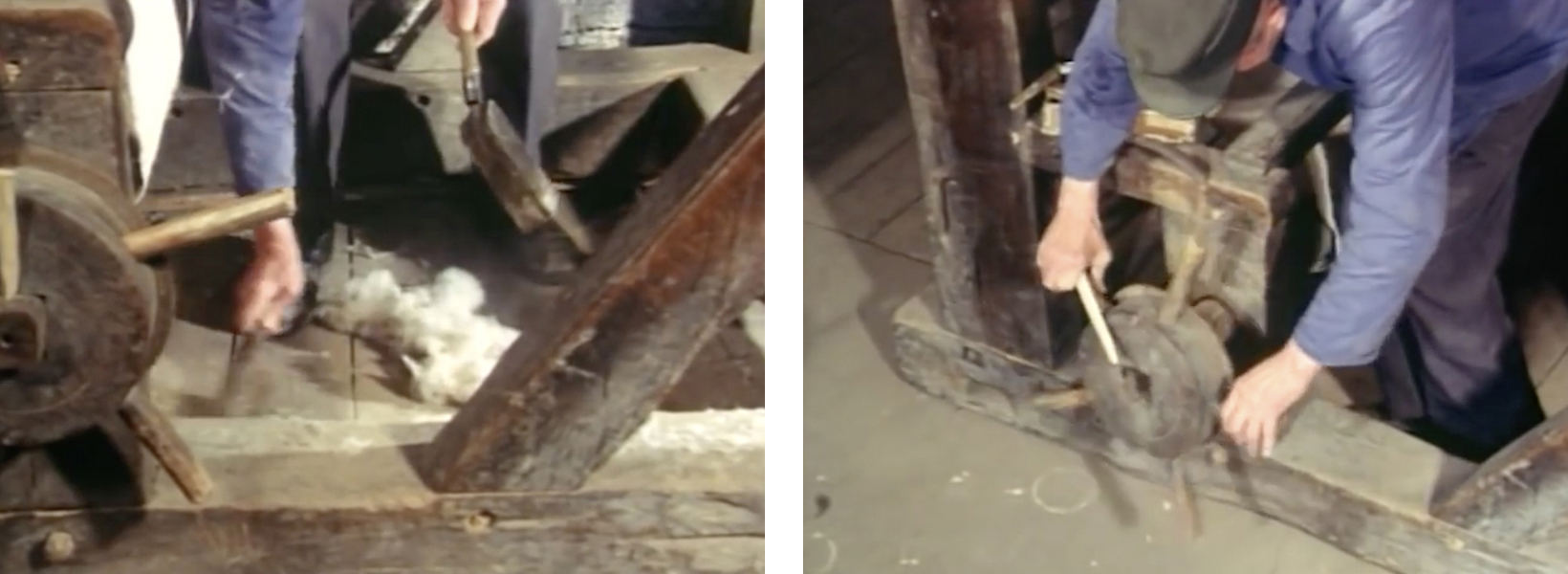

Otto Klos now replaces the small, serpentine brake pawl with a large, heavy one. This must be able to withstand the pressure of the tensioned warp during weaving.

Later, the weavers can use a cord to release the lock on the warp beam, by one tooth of the wheel at a time, so that the warp can be advanced.

Once Wilhelm Mosel has woven about 10 cm of fabric he can insert the temple. This consists of two slightly curved, flat pieces of interlocking wood. They have metal teeth at the ends, which the weaver hooks into the edges of the fabric. The temple keeps the working area of the cloth taut during weaving.

The lay beats well and the shuttle can be thrown easily through the shed. The loom is working.

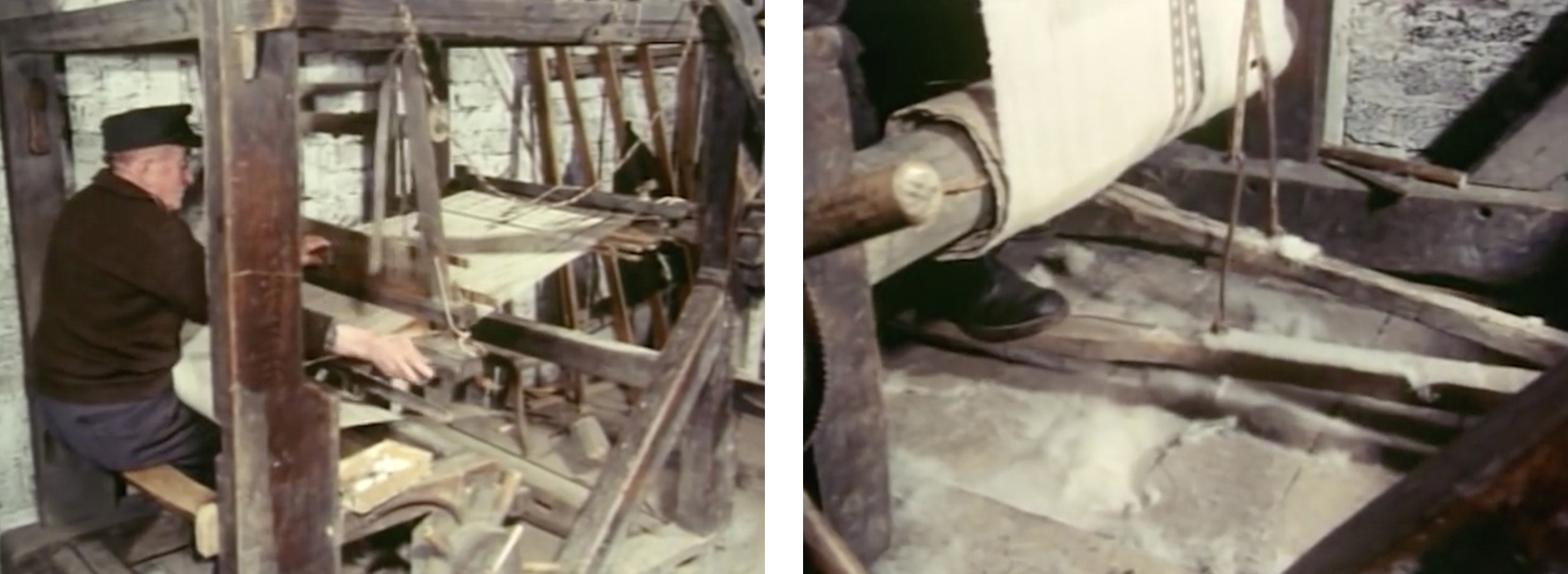

The following day Wilhelm Mosel continues the work. He has already woven about a meter and a half of fabric wound on the breast beam.

A faster linen weaver could weave up to 10 cubits, or about 5m of cloth in one day.

One can clearly see how the shafts form the shed into which the shuttle carrying the weft is thrown.

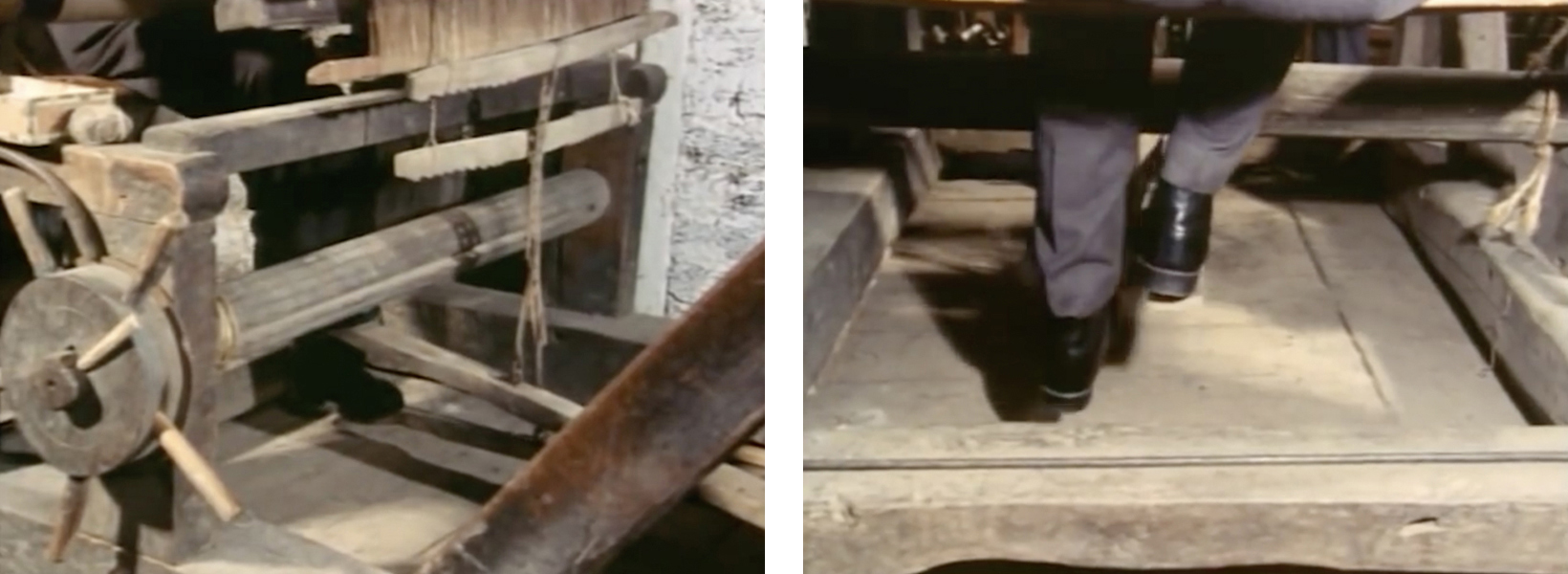

With this simple plain-woven linen every second thread in the warp is lifted when a treadle is depressed. After throwing the shuttle and beating with the lay, the weaver steps on the other treadle so that the warp threads that were previously on top are now pulled down and those on the bottom are lifted. This is how the typical weaving rhythm is created.

After Wilhelm Mosel has woven enough fabric he can stretch the finished section of the cloth on the cloth beam. To do this, the cord from the breast beam is first undone. The men unwind the beginning of the woven fabric.

Otto Klos places the willow stick with the beginning of the warp in the slot on the cloth beam and then rolls up the cloth with the help of the locking wheel.

The fabric and the warp are tightened by turning the cloth beam which retains its tension with the locking device.

Once the men have done this, the preliminary stage is complete.

Albert Gebert has replaced Wilhelm Mosel as weaver.

On a farm, depending on the workload, several people would sometimes take turns weaving linen for their own use. If linen was being produced for sale, however, only one weaver would work on it. In this case great importance was attached to a uniformly woven cloth. Since every weaver has a slightly different beat, a change of weaver is immediately noticeable through a denser or looser weave.

The weft bobbin is empty. So Albert Gebert puts a new bobbin in the shuttle.

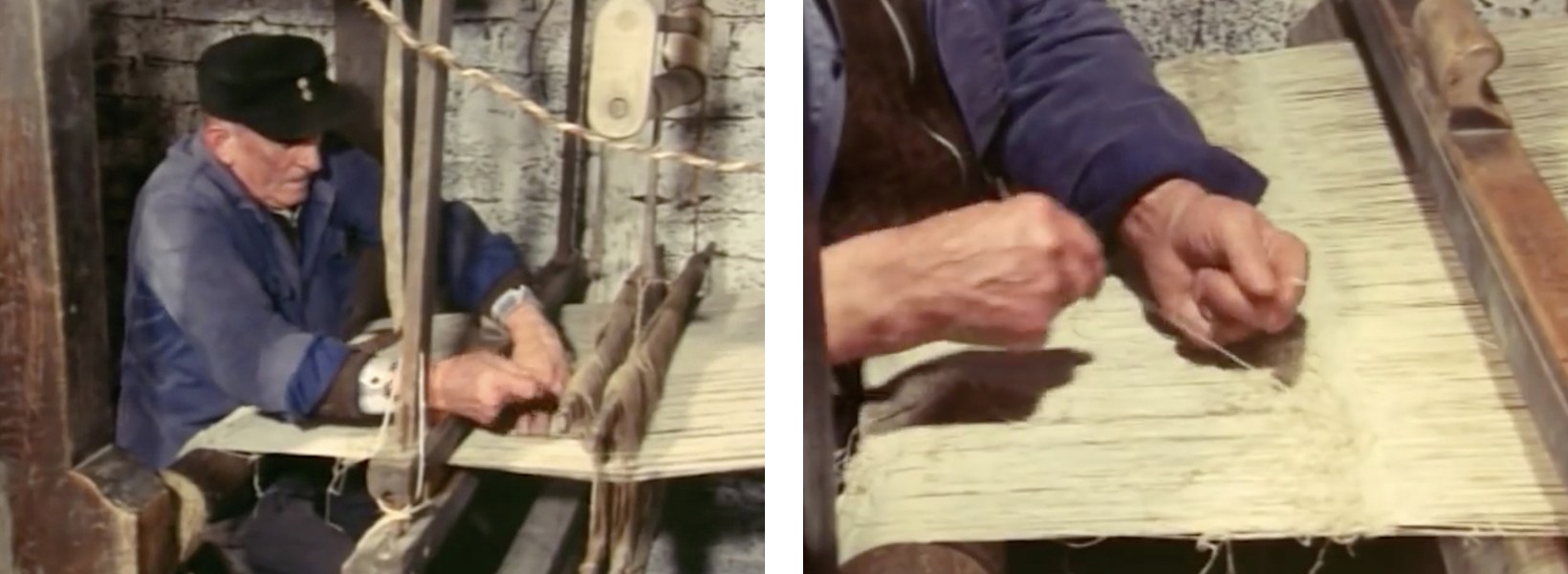

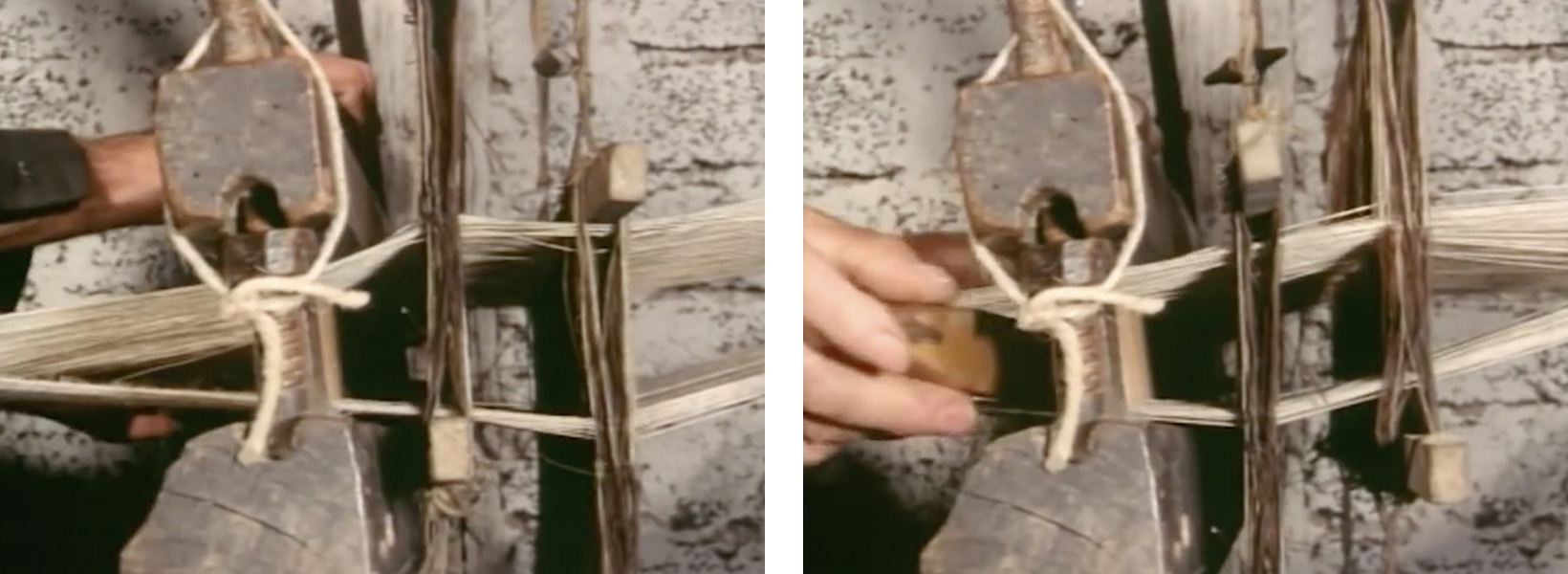

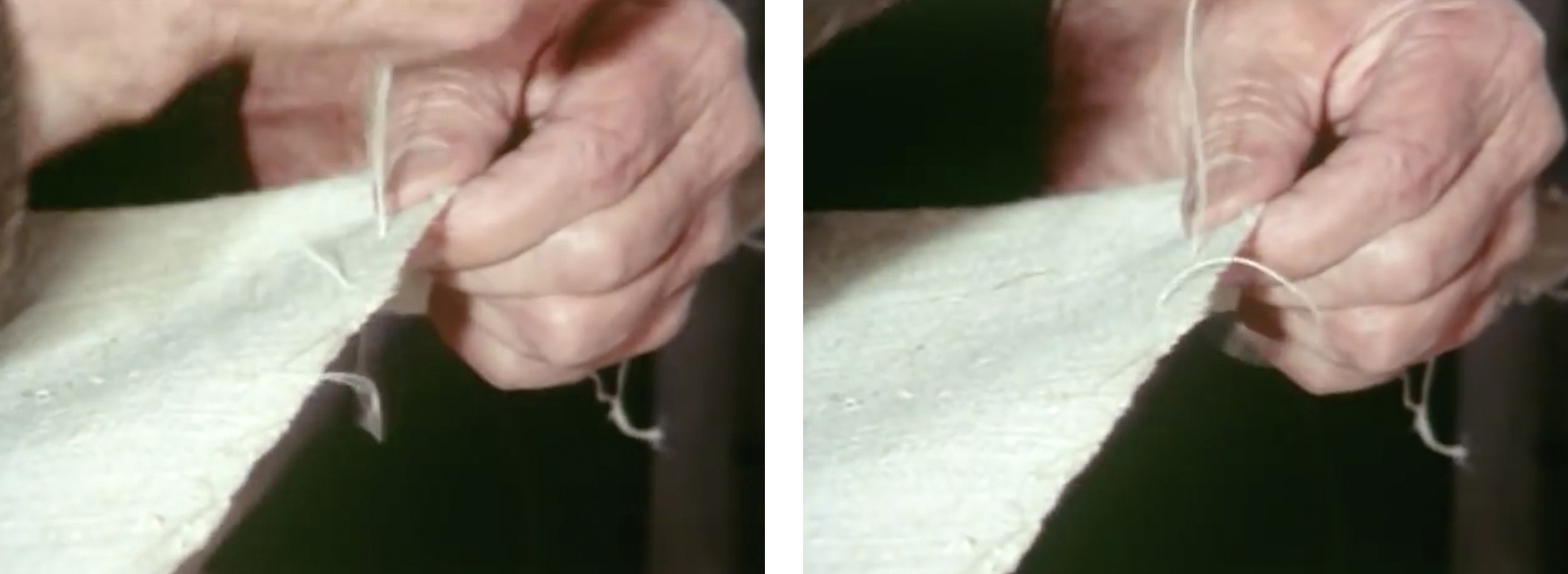

Old and new threads are tied together with the weaver’s knot.

So that there is always enough weft to hand, it must be wound onto the hollow elder sticks as the weaving proceeds. This is done by Otto Klos, using the bobbin winder. The hollow stick is first placed on the spindle of the winder. The thread from a large spool of linen yarn left over from the warp is now wound onto the small bobbin.

While Otto Klos turns the wheel with his right hand, he guides the thread evenly onto the elder stick with his left hand.

Winding the weft was primarily the work of women and children. From 1850 onwards, professional weavers faced increasing competition from fabrics that were produced more quickly and cheaply on an industrial scale. If they wanted to maintain their orders and earnings, they had to use all the labour available in the family. In commercial home-weaving, children as young as five were therefore used for weft winding.

They often had to sit for hours at the bobbin winder, which had a serious impact on their mental and physical development. In the school records of the time one often reads complaints about this work obligation and the associated school absence.

Again and again during weaving Albert Gebert moves the temple further back to keep the cloth taut in the working area.

He smooths the selvedges with the ‘salwend‘. This prevents the edge from becoming uneven or fraying.

Unlike warp warping and threading, plain linen weaving requires no special skills. Intricate pictorial patterns and weaves were typically crafted on special looms. These had up to 25 shafts and treadles, the operation of which required a high level of concentration and, most importantly, long manual training. For rural weaving like this, however, only simple looms with a maximum of 2 to 4 shafts were used. This rural linen weaving was therefore drab, monotonous work.

In the Hunsrück, rural linen weaving had existed for several centuries but only became very important in the 19th century. This is documented by Prussian trade statistics. For example, in 1817 only 90 linen looms were registered in the district of Simmern, but by 1861 that number had already increased to 1167, the peak number in what was then the Rhine province.

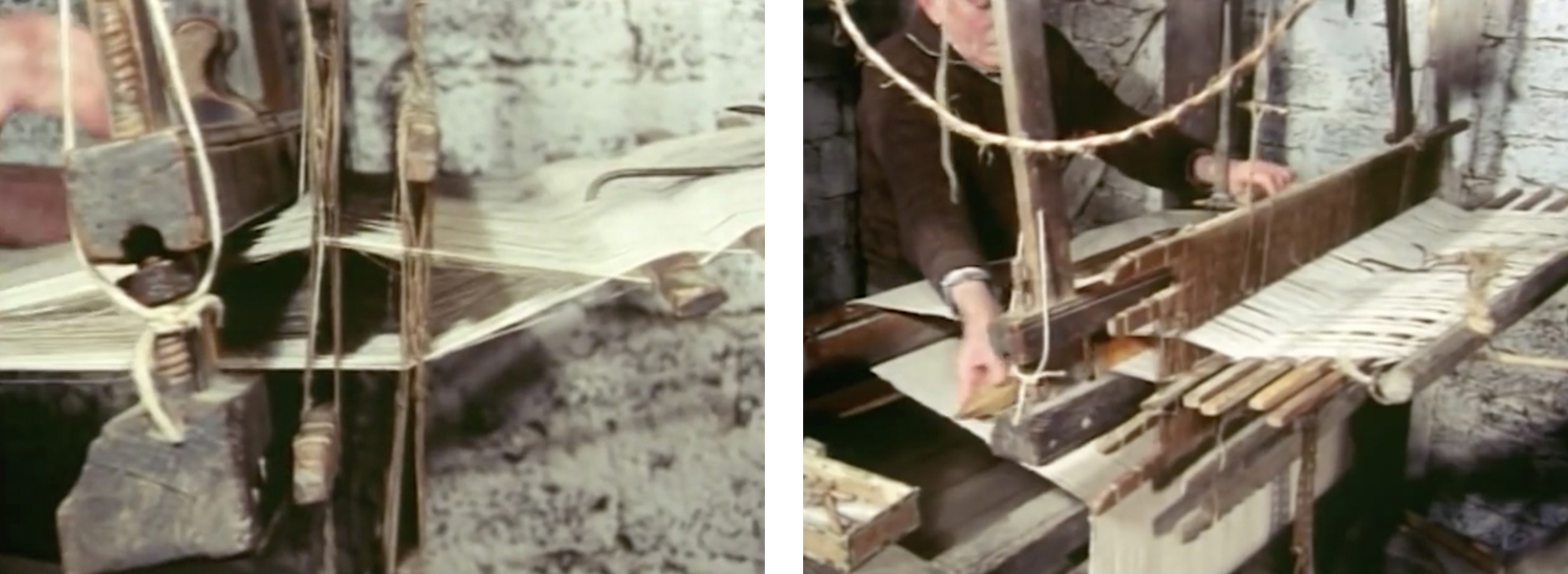

You can clearly see the shed. Here the weaver throws the shuttle through the shed by hand. The flying shuttle did not become widely used in this region until the beginning of the 20th century. Invented in England as early as 1733, this device allows the shuttle to be thrown back and forth by a short pull on a cord attached to a driving mechanism, considerably speeding up the weaving process.

Again and again, the weaver releases the locking mechanism in order to advance the warp and wind up the finished fabric.

Occasionally it happens that individual warp threads break. They must be knotted immediately so that there are no faults in the fabric.

Albert Gebert guides the thread through the reed and attaches it to the temple so that he can continue weaving. The end of the thread will later be sewn into the finished fabric and cut off.

The weaver often has to dress the warp threads, that is, coat them with the flour paste. This makes them smoother and more hard-wearing.

To do this, he pushes the cross sticks apart and pulls the warp threads taut.

Albert Gebert applies the rye flour paste thinly, from above and below, with two brushes.

After about three days of weaving, the warp is completely unwound from the warp beam. It must be lengthened so that the last section can also be woven.

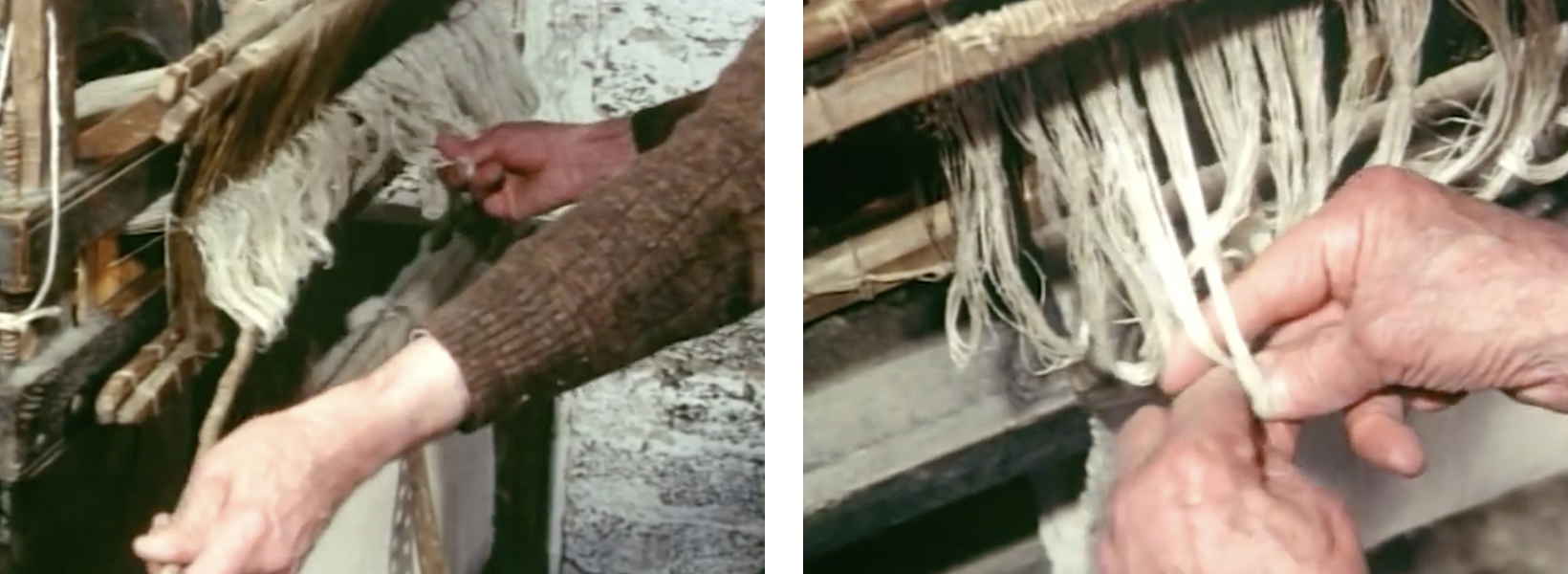

Wilhelm Mosel first detaches the willow stick that goes through the end of the warp – the so-called ‘thrum’ – from the warp beam.

Next, the men attach a batten with iron hooks on to the stick. This extension, like the wooden weight, is also called a ‘donkey’ in the language of the weavers.

They attach the cords from the donkey to the warp beam.

Now the weight can be hooked in again and the warp tightened.

Otto Klos smooths the end of the warp with the rest of the flour paste.

Weavers who did this work as their main occupation often developed rheumatic and cardiovascular diseases from sitting bent over the loom for 10 to 14 hours in a workshop with only moderate heating.

The burden on the internal organs, such as the stomach, was considerable. There were also eye infections because the workshops were insufficiently lit. The weaving of linen, like wool and cotton, was a dusty affair. Professional weavers therefore often contracted tuberculosis.

These typical weavers’ diseases were rare in rural weaving becasue the farmers combined weaving with agricultural work.

The cross sticks in the slowly advancing warp have almost reached the shafts. This make it difficult to raise and lower the shafts to form the shed. Therefore, the first sticks are taken out of the cross.

The weaver works a willow stick into the end of the linen cloth. The stick, along with the remant of cloth and the end of the warp, will soon be cut away from the main piece of woven cloth.

This prevents the remaining warp from slipping out of the reed and heddles.

When weaving a new linen fabric, this stick will be inserted into the slot in the breast beam.

Wilhelm Mosel now uses a knife to cut off the cloth in front of the willow stick that was woven into it.

The weaver sews the raw edge of the cloth with a linen thread to prevent it from unravelling

To remove the cloth from the loom, Otto Klos first unhooked the weight. Wilhelm Mosel carefully pulls out the cross sticks that are still in the end of the warp.

The two men remove the cord attaching the donkey to the warp beam. The weaver then detaches the donkey from the willow stick at the end of the warp.

The remnant of cloth with the woven stick and the end of the warp have remained in the harness. This will be needed later to set a new warp on the loom. This saves the very time-consuming process of passing individual threads through the eyes of the heddles and through the reed.

Wilhelm Mosel inserts the willow rod into the breast beam, pulling the harness forward and a little and securing it.

This allows the weaver to easily pull the rod out of the loops at the end of the warp.

The gangs of the warp form separate loops hanging down behind the shafts. Wilhel Mosel pulls these through each other in such a way that they are not damaged while the gear is moved and stored.

Now the men can detach the harness from the treadles and the pulleys. The reed with the warp remnant is also taken out of the lay.

To remove the cloth from the loom, the helper takes down the lay.

To make room in the loom Otto Klos undoes the brackets for the treadles and puts these aside too.

So that the fabric does not get dirty when it is taken off and rolled up on the floor, Otto Klos sweeps away the fiber dust produced during the weaving process.

He then releases the locking wheel from the cloth beam

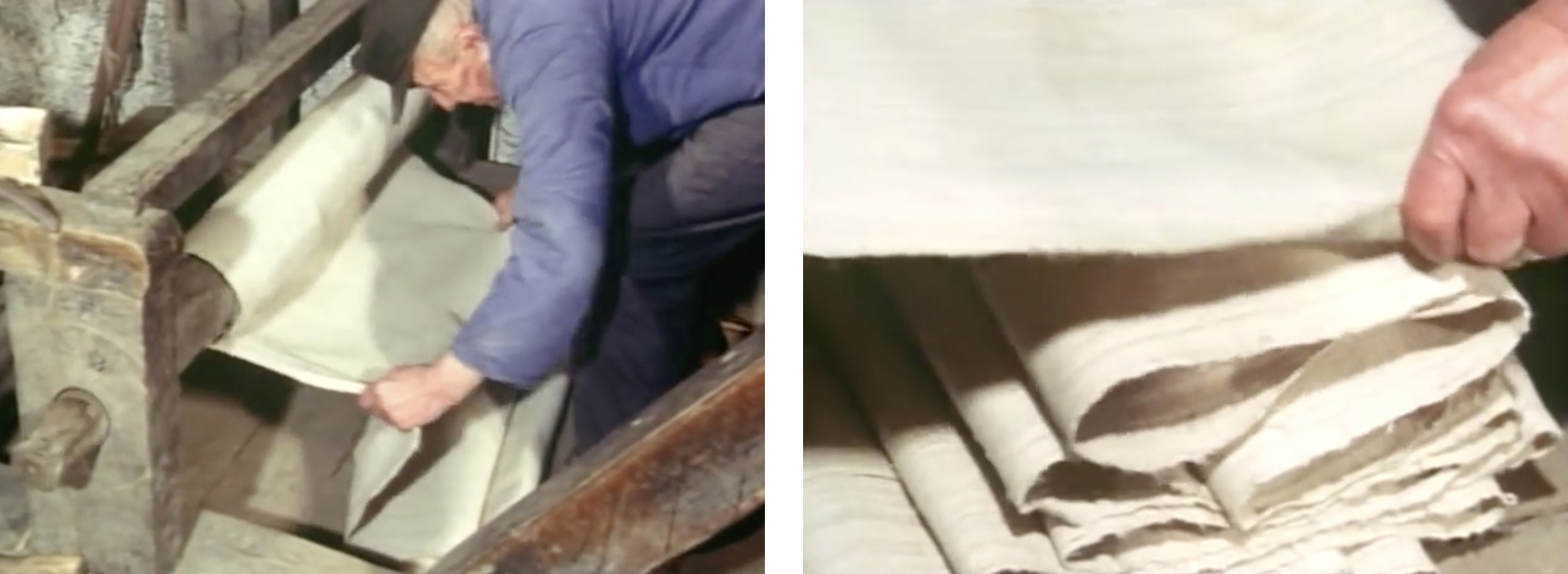

The cloth – more than 10 m long – can now be unrolled from the cloth beam and folded on the floor. The willow stick will be removed from the cloth later.

Up until the 19th century there was a great need for linen fabrics in the home. Textiles such as tablecloths, towels, bed linen, but also underwear and summer outerwear consisted mainly of linen. However, before the fabric could be processed or sold, the weaving faults had to be repaired, protruding threads sewn up and the fabric washed and bleached in the meadow. After this, the cloth sometimes underwent further finishing, such as the so-called Blue-printing (Blaudruckverfahren) resist dying process.

The fabric was rolled up and stored in a chest or cupboard until it was bleached after the hay had been harvest in summer or early autumn.