This post is about the handloom from North Lopham, Norfolk, now in the collection of Bankfield Museum in Halifax. This old loom has been in storage since it was acquired in 1925 following the closure of T.W. & J. Buckenham, manufacturer of the finest linen in England. I am grateful to the curators for facilitating my visit to take photographs and measurements in May 2023.

The village of North Lopham in Norflok was the last place in England where linen was manufactured on handlooms. The knowledge and skills needed to bring out the inherent beauty of this notoriously difficult material had evolved over centuries, handed down from generation to generation. (See this post for more about Lopham Linen.) When production ceased, and the old weavers died, much of this knowledge was lost. The tools they used, however, can provide some insights into their methods.

When T.W. & J. Buckenham, the last of the Lopham linen manufacturers, closed in 1925, some of the looms were acquired by museums. The only one I have been able to trace went to Bankfield Museum (part of Calderdale Museums) in Halifax. In May 2023 I visited the storage facility where it has lived for most of the last century. It is the biggest loom I have ever seen, with some unique and fascinating characteristics.

The loom, which I refer to as the Bankfield loom, appears never to have been catalogued or displayed to the public. The museum curators once descibed it as “basically in 18th century type of loom with twenty sets of heddles selected and lifted by ‘witch’ engine, worked by a single treadle.”1 It was described by Percy Beales as “the most interesting of all” the Lopham looms (see this post for more about Percy Beales).

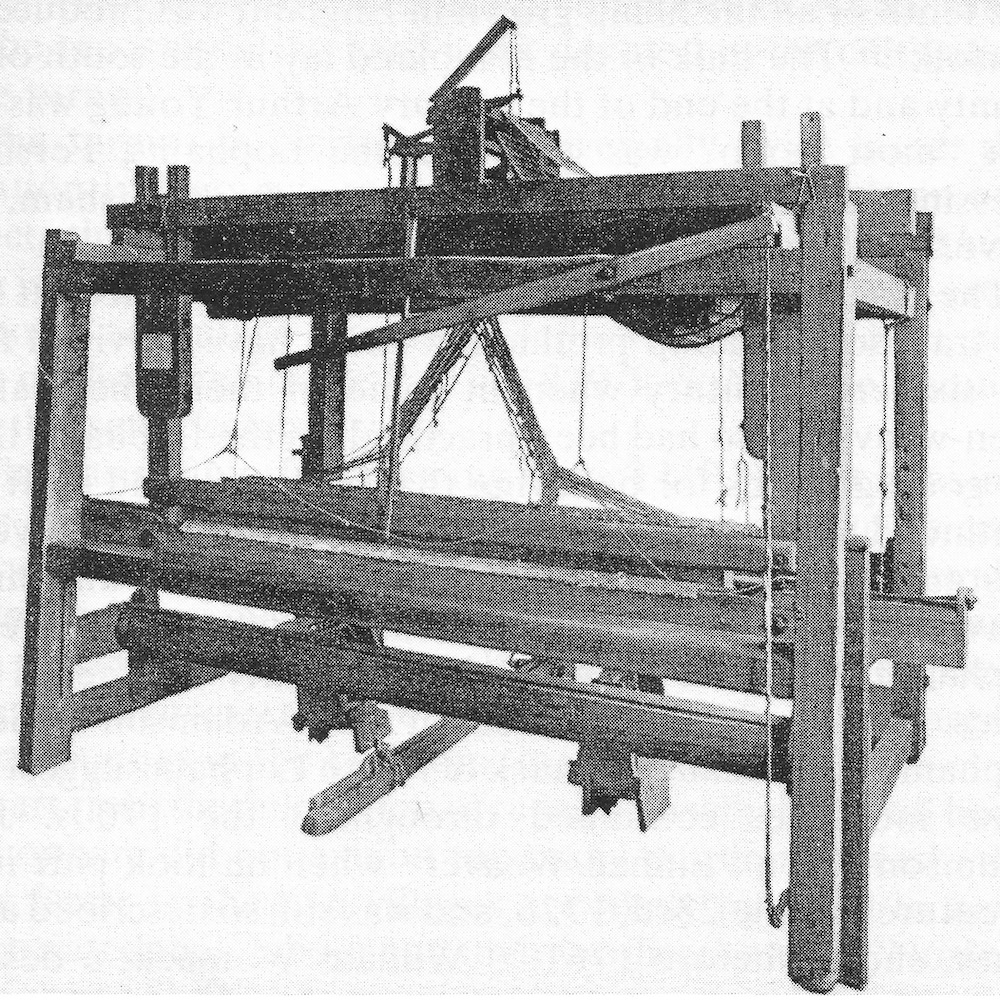

The photograph above is included in Michael Serpell’s book A History of the Lophams with the caption: “18th century hand-loom from North Lopham Limes. Now at Bankfield Museum, Halifax. By courtesy of the Calderdale Museums Service”.2 In the photograph the loom appears to be in full working order, suggesting it was photographed in North Lopham or re-assembled and set up in Halifax before being put into storage.

Any further information must be gleaned from a study of the loom itself. I have arranged my photographs to focus on the following:

- The construction of the loom’s timber frame, with overall dimensions.

- The batten or lathe assembly, including the fly-shuttle arrangement,

- the cloth beam and warp beam, with brake mechanisms.

- the ‘witch engine’ shedding device, harness and heddles.

Loom Frame and overall dimensions

The loom frame has a straight-forward ‘four-post’ configuration, with a full-height post at each corner. This type of loom was often referred to as the ‘Old English Loom’, although there is nothing peculiarly English about it and looms of this type were found all over Europe.3 These looms are very sturdy, able to withstand the high tension and heavy beating needed for linen weaving. They tend to be deep from front to back, with a large distance between the warp beam and the heddles, and with open sides giving easy access to the warp for the application of a starch dressing.

The timber for the frame appears to be pine. The unusually wide frame is 272cm (8′ 11″ inches) wide and 172cm (5′ 8″) deep, measured from the outsides of the corner posts, which are about 181cm (5′ 11″) tall.

The corner posts are about 15cm (6″) deep and 10cm (4″) wide. The bases are irregular and appear to have decayed. Damp conditions are beneficial to linen weaving, and old linen looms were often set into earthen floors and therefore prone to rot.

The main joints are mortise and tenons, with a double tenon joining the breast beam to the corner posts. Some of these joints are strengthened with quare-headed iron bolts.

Batten and fly-shuttle assembly

The heavy batten (or lathe, or lay) assembly has been detached and no longer swings. It is unusual in having forked ‘swords’ each made from three pieces of timber. In the old museum photograph it can be seen hanging from supplementary beams whose ends sit on the cross rail running across the loom above the weaver’s head. It is curious that the swords do not straddle the top of the loom’s side frame as I would expect, suggesting that perhaps it had once belonged to a slightly narrower loom.

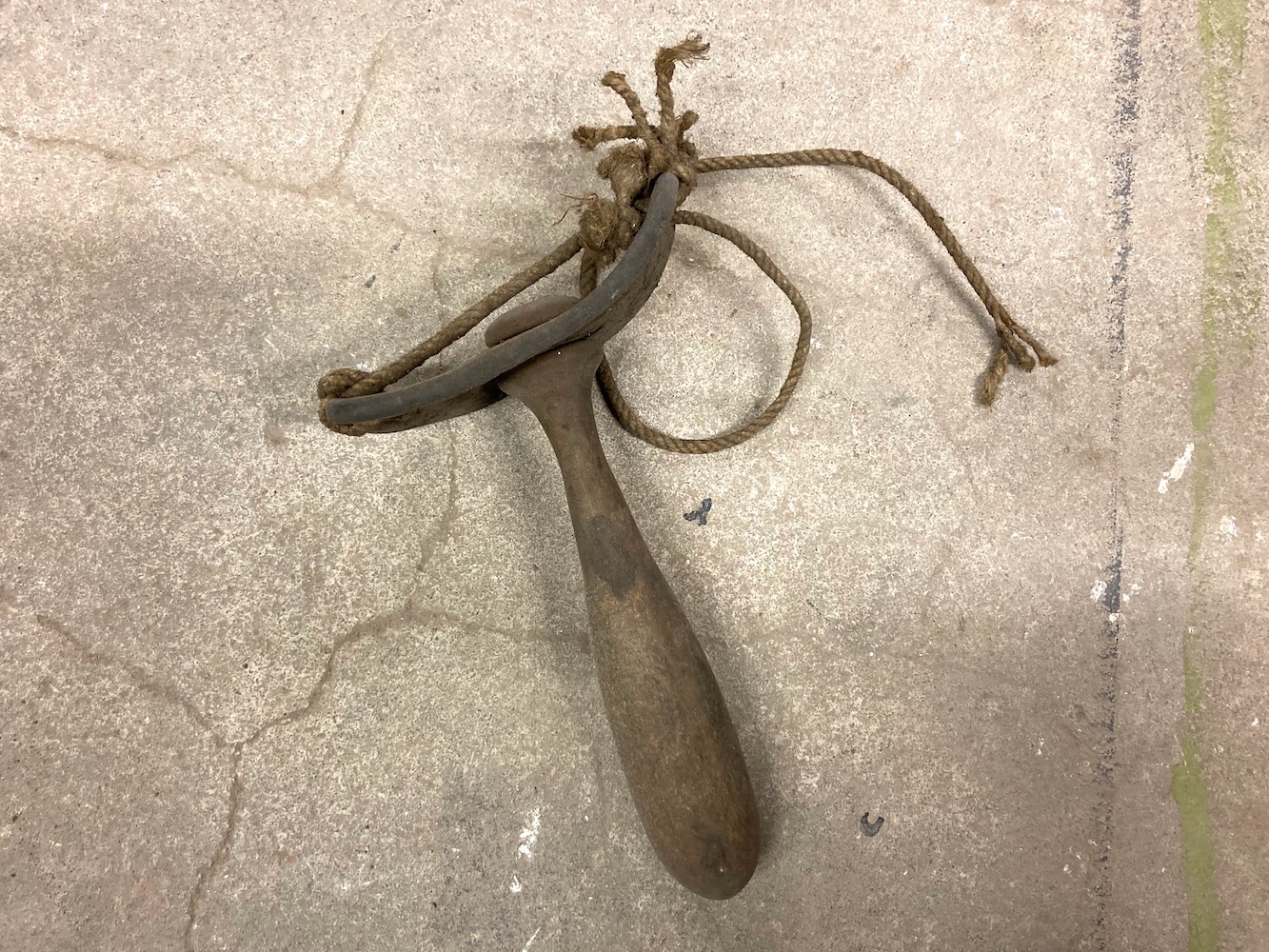

The loom is fitted with a fly-shuttle assembly. The pickers for propelling the shuttle along the race are made from three pieces of thick leather sliding along an iron rod (very similar to the pickers on one of the damask looms in the Irish Linen Centre in Lisburn). The cords tying the pickers to the batten and the picking stick have perished, and the picking stick, once held in the weaver’s hand, is detached and lies among other odds and ends in a box on the floor.

Cloth beam & warp beam

The cloth beam is about 17cm (7″) in diameter, fitted with an iron ratchet brake at the right-hand end. The ratchet wheel is about 29cm (12″) in diameter and has roughly 100 teeth. The beam has an iron axle whch rests in mortises in the loom frame.

The warp beam is of similar dimensions to the cloth beam, and also has an iron axle. There is a slot running the length of the beam to accept a thrum stick at the end of the warp. The axle at one end of the beam turns in a wooden bearer which can be raised or lowered to adjust the height of the beam. The axle at the other end rests in an iron bearer which can also be adjusted vertically. At this end the beam is fitted with a ratchet brake 36cm in diameter with 44 teeth. A label attached to the ratchet wheel indicates it was made by Garside & Derring, Brassfounders of Halifax, suggesting it was fitted after removal from Lopham, perhaps as a replacement for a broken one. The ratchet wheel was braked with a pawl lever on the under-side. A broken cord is tied to the end of the pawl, alothough it is not clear how this was operated.

It is not immediately obvious how the warp was advanced. The museum photograph shows a long wooden lever pivoted on the upper front cross rail. The lever’s handle is above the weavers head to the left, and its other end is attached to a cord running down to a metal lever near the foot of the right front-post. It is likely that this was part of a ratchet mechanism which turned the cloth beam when the handle over the weavers head was pulled down. A similar ratchet system exists on the linen looms in Lisburn and the Ulster Folk Museum, though without the long wooden lever. The Bankfield loom is much wider, making it difficult for a weaver to lean down to reach the lower lever, hence the need for the second overhead lever.

Witch engine and harness

Sitting on top of the loom in the centre is a ‘witch engine’ operating 20 heddle shafts. A witch engine is similar to a dobby mechanism (according to some authorites a witch is a just a different name for a dobby). Both are mechanisms for selecting and lifting a number of shafts, using a single treadle. According to John Tovey’s (1965) The Technique of Weaving: “The difference between the dobby and the witch lies in the selection mechanism. The dobby has large square pegs set in large holes, and the pegs push the hooks off the lifting knife, the witch has fine straight pegs like match sticks and the hooks are pushed onto the lifting knife.” 4

The frame of the witch engine appears to be hardwood of a finer construction than the rest of the loom, and is almost certainly a later addition. Some components, including the ‘lags’ holding the pegs, are missing.

The hooks of the witch engine are still tied to 20 ‘coupers’ immediately below it. The coupers are pivoted at the left-hand end. The cords which would have connected the coupers to the heddle shafts have been cut, but the museum photograph shows how each shaft was tied at four points along the length.

The intricately tied heddle shafts now lie in a heap between the batten and the cloth beam.

Uses?

I am unsure what kind of linen was woven on this loom. Norfolk Museums hold a collection of Lopham linen (see my post), consisting mainly of fine damask tablecloths and huckaback towelling. Damask required a Jacquard loom, while even the most complicated of the huckaback could be made on a loom with only five shafts. The Bankfield loom, with twenty shafts, is capable of making very wide cloth of a complexity somewhere between the huckaback and the damask. The Thomas Jackson manuscript, written in Yorkshire in the eighteenth century, contains drafts for fancy linen twills needing 16 shafts, while the Ralph Watson manuscript c.1800 includes drafts for ‘damask diaper’ needing 15, 20, 25 or 30 shafts. According to White’s Directory for Norfolk of 1854, “the two villages (North & South Lopham) have long been celebrated for the manufacture of linen, and though little yarn is now spun here by hand-wheels, there are upwards of 100 looms employed weaving sheeting, diaper and huckback, etc., which are mostly sold unbleached by the manufacturers.”5 Perhaps the Bankfield loom was chiefly used for making some kind of ‘diaper’, perhaps a fancy twill like those in the Thomas Jackson manuscript, or a damask diaper as woven by Ralph Watson, although I am not aware of any cloth quite like this from Lopham in the collection of Norfolk Museums to help substantiate this.

Notes

- Michael Friend Serpell (1980): A History of the Lophams. p.198

- Ibid., 112.

- see for example Luther Hooper (1910) Handloom Weaving Plain & Ornamental. p. 88.

- John Tovey (1965) The Techniques of Weaving. p.15-16.

- The quote from White’s Directory is taken from a newspaper cutting c1930s, preserved in the Rita & Percy Beales archive in the Crafts Study Centre: RPB 2/1/4.