Late last year I finally made it to the North Yorkshire County Records Office to look at the manuscript known as The Weaver’s Guide: Linen Designs by Ralph Watson of Aiskew. In this post I share some photographs of the manuscript, along with some background about Ralph Watson and my speculations on the techniques he may have used. I have written before about how I first learnt about the manuscript, back in 2020, and about some cloth I made from one of Ralph Watson’s drafts in 2021 & 2022.

The manuscript

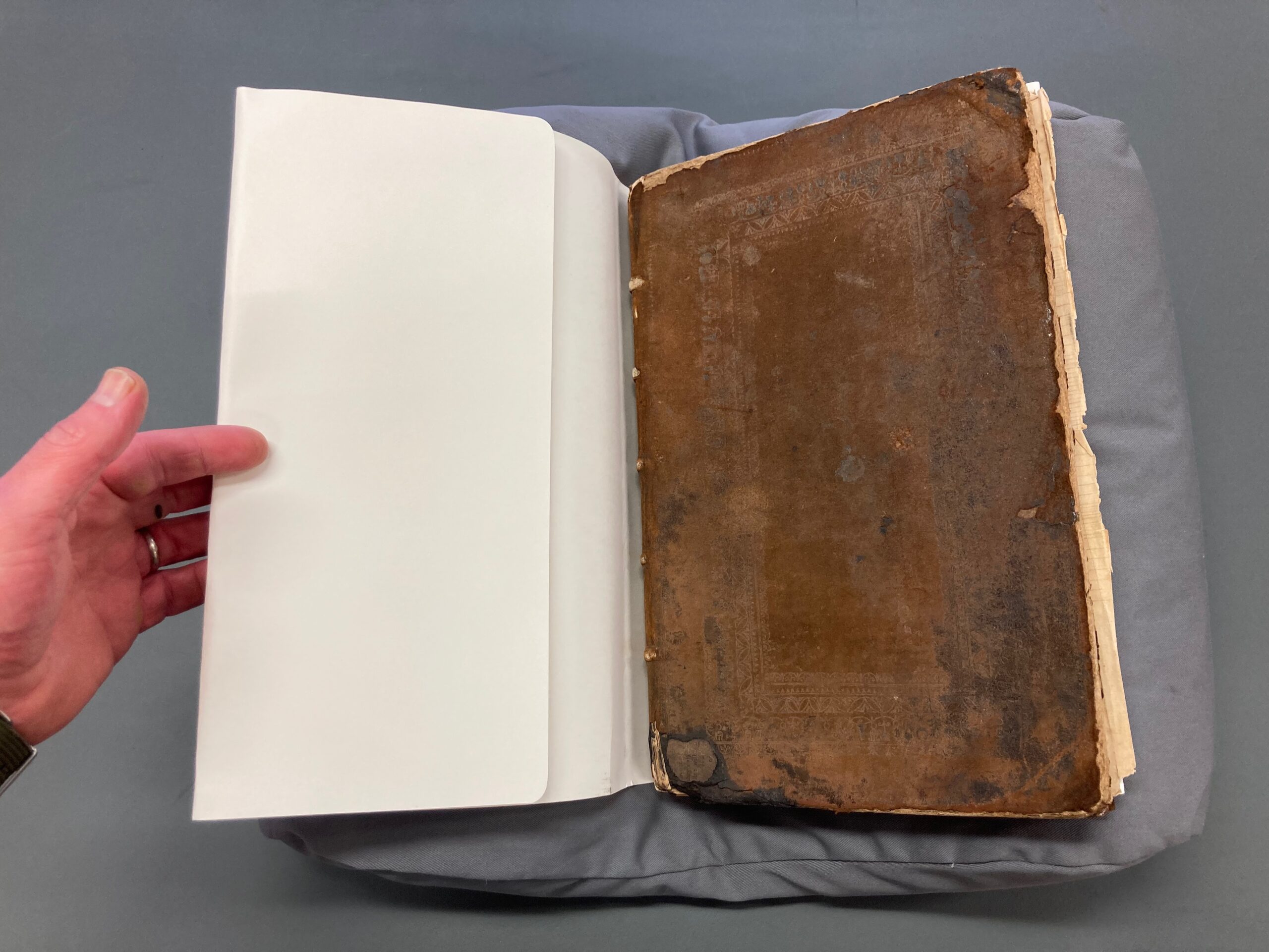

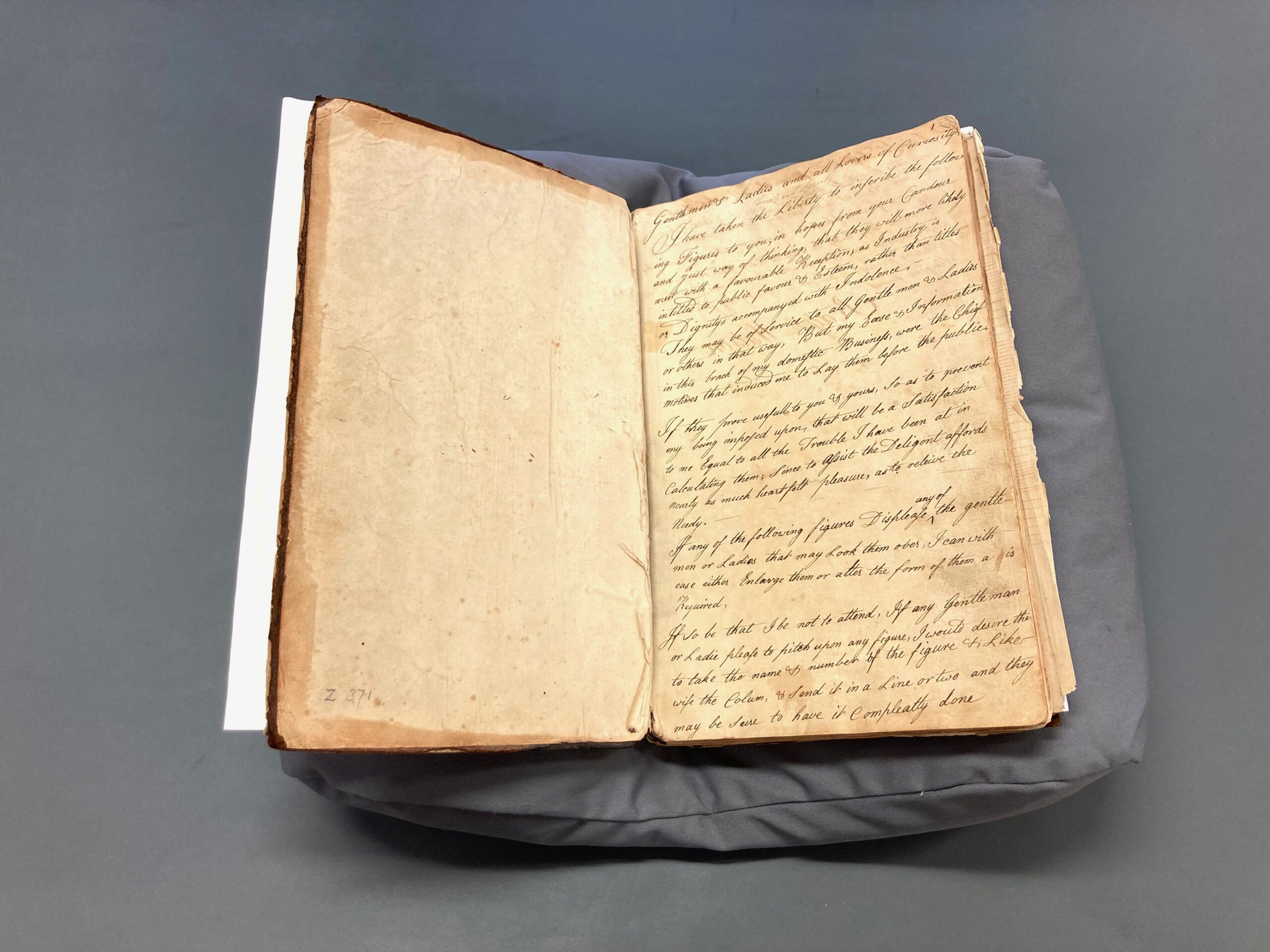

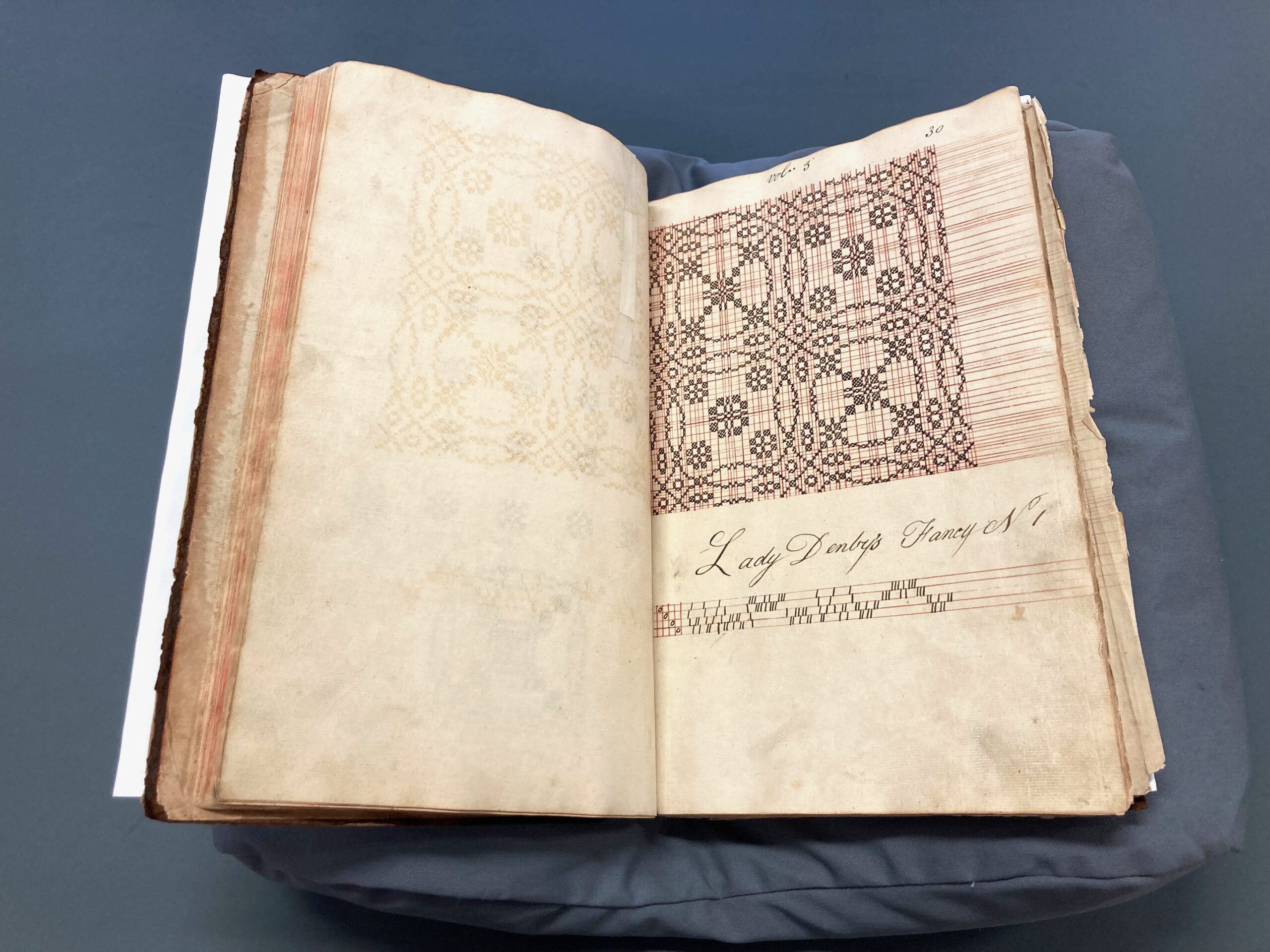

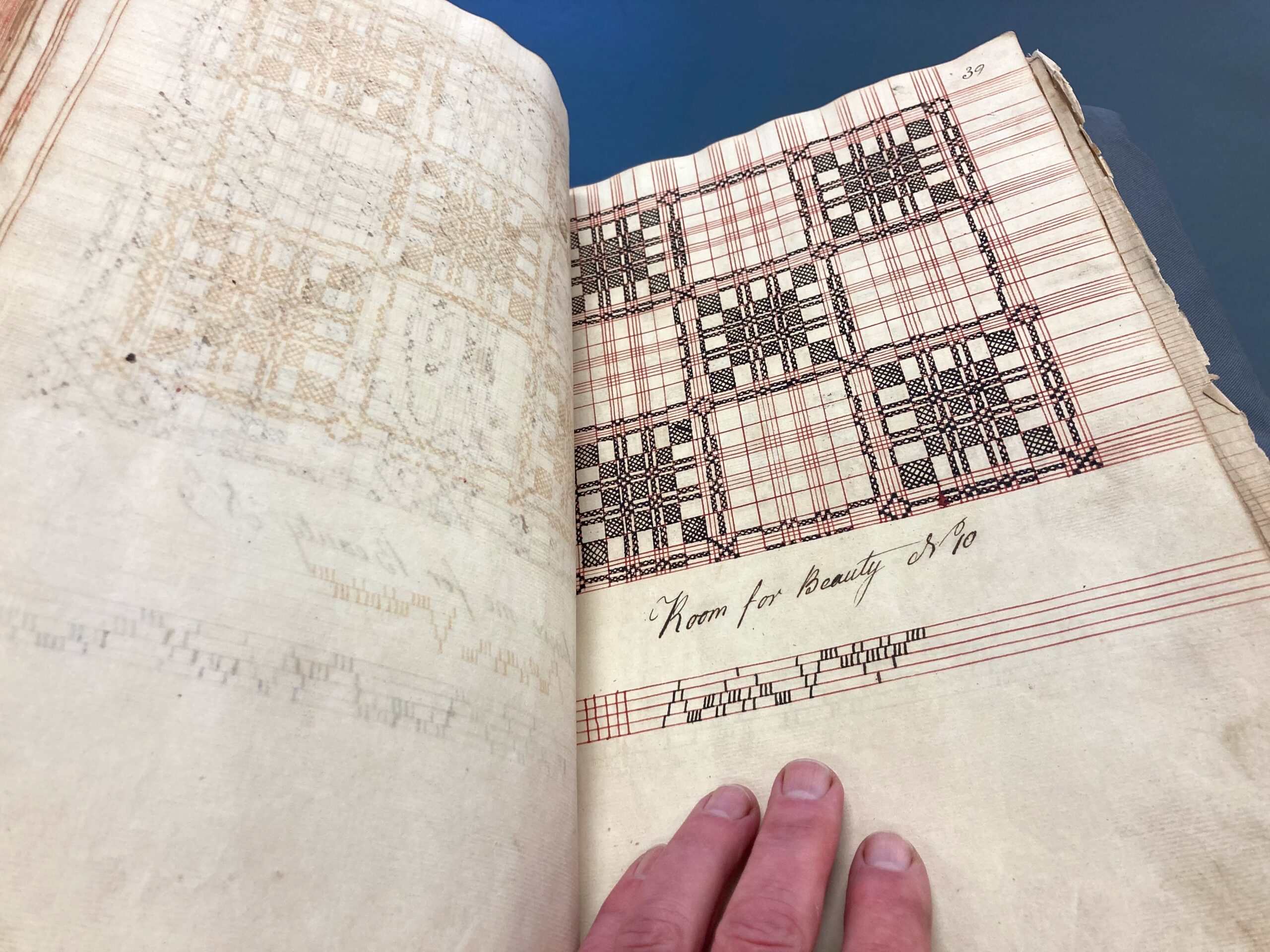

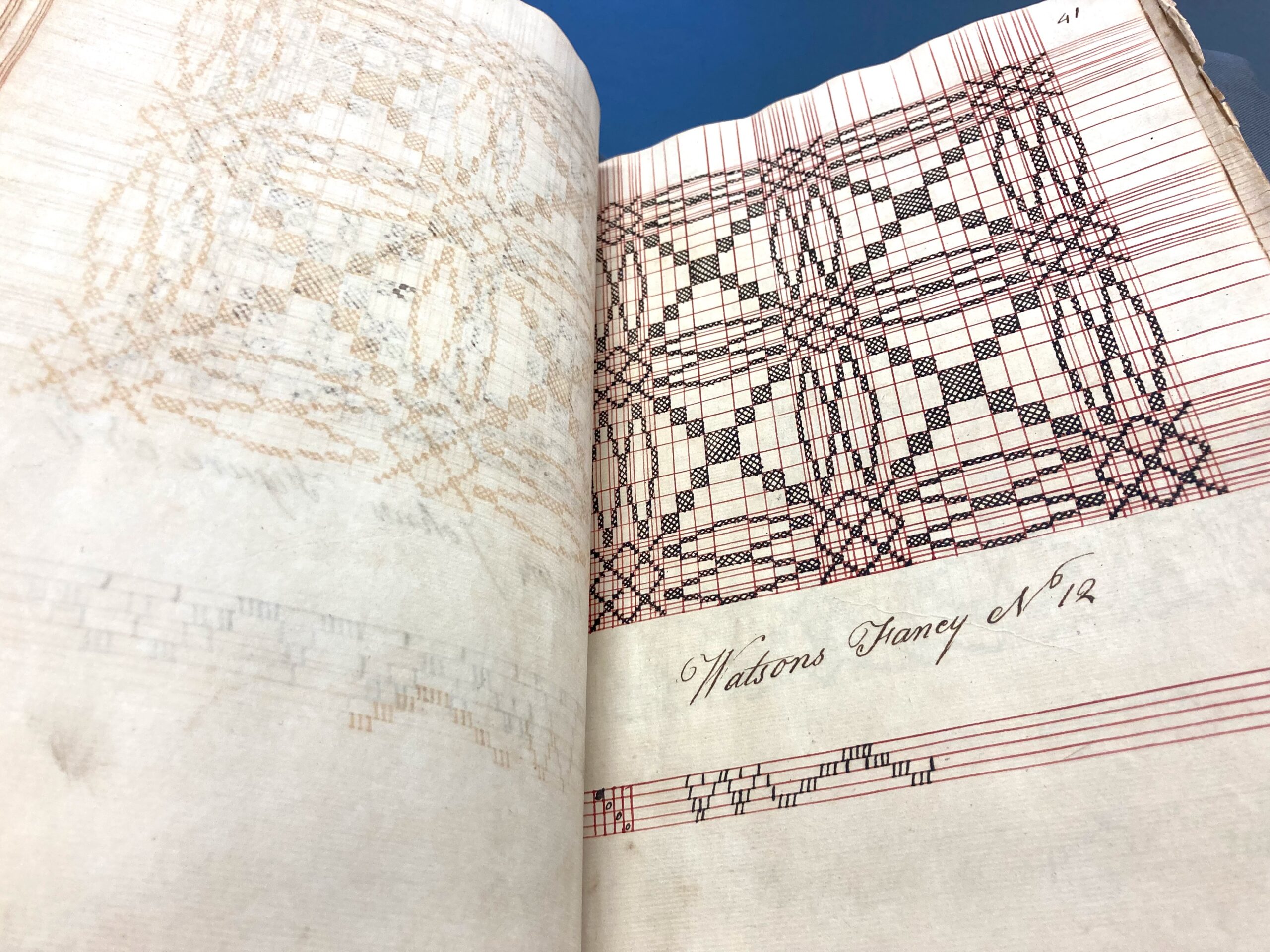

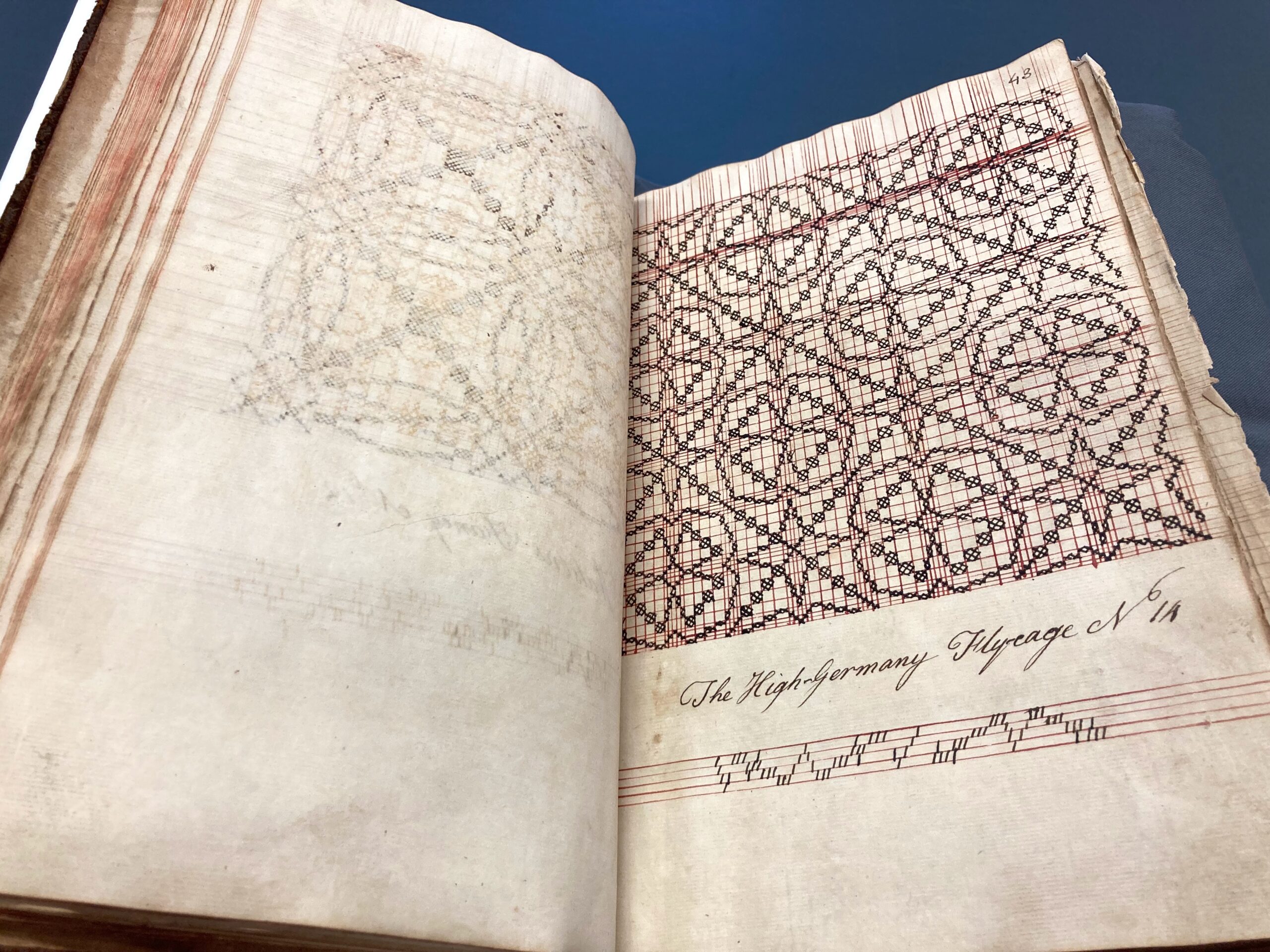

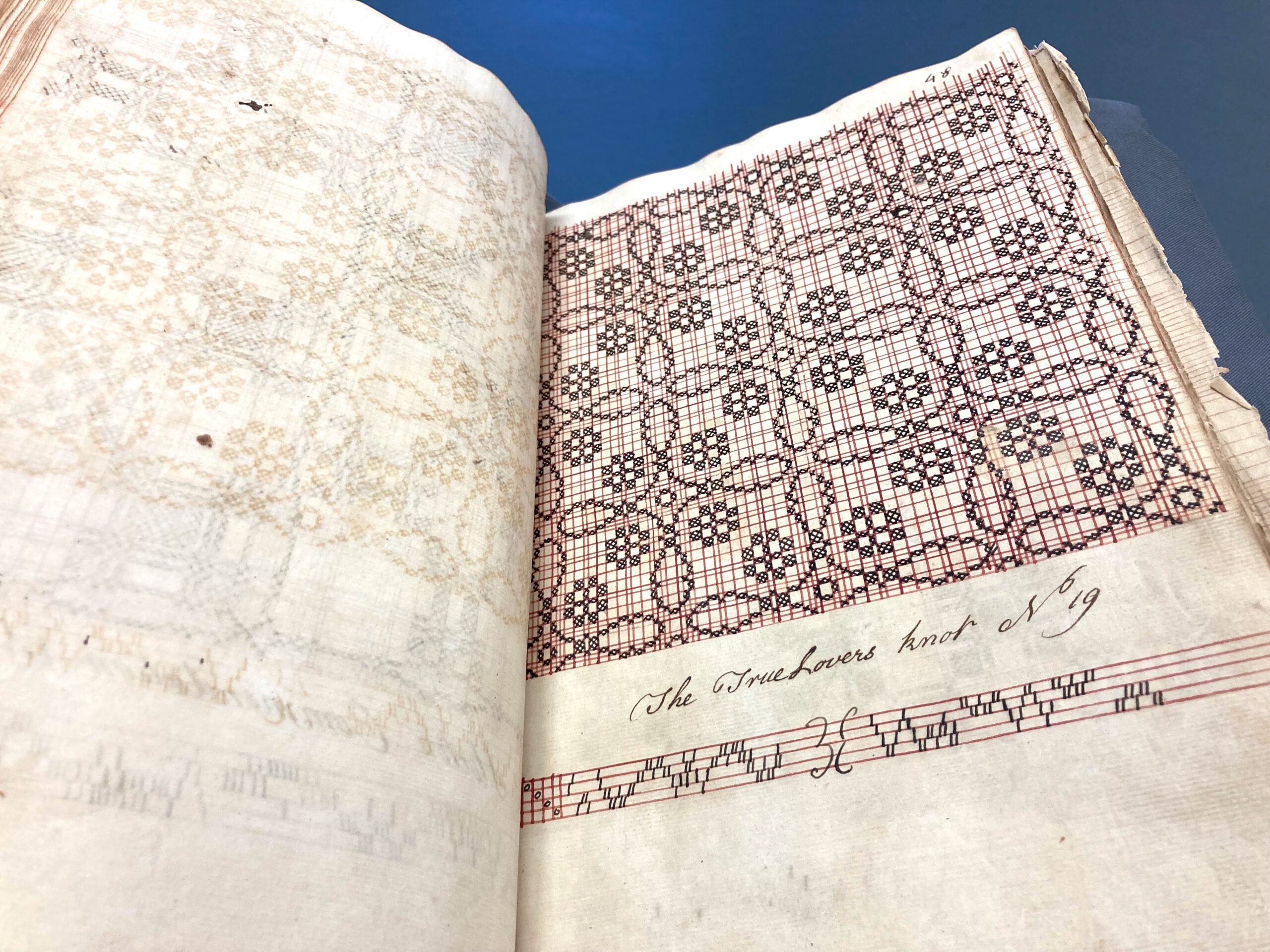

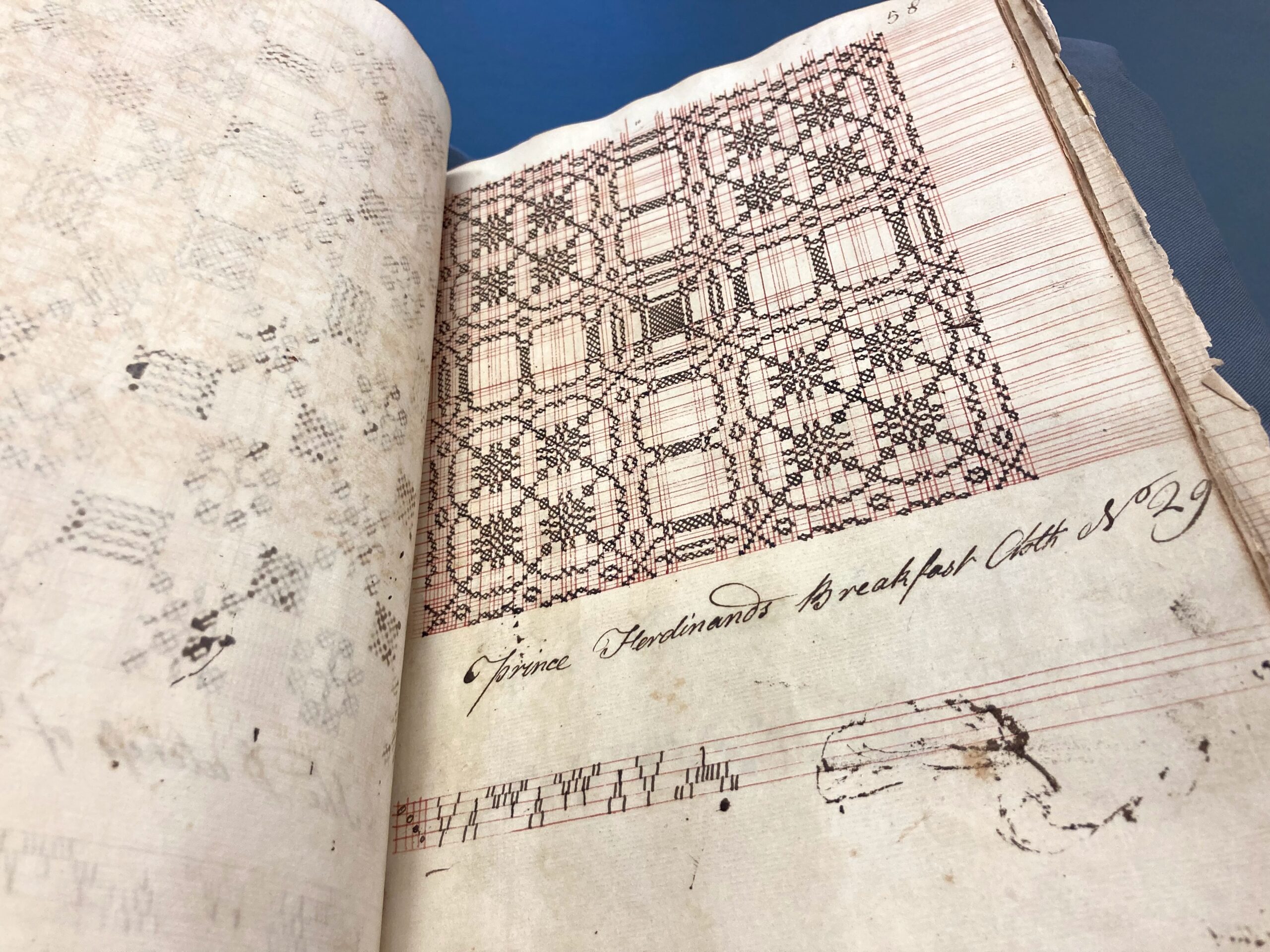

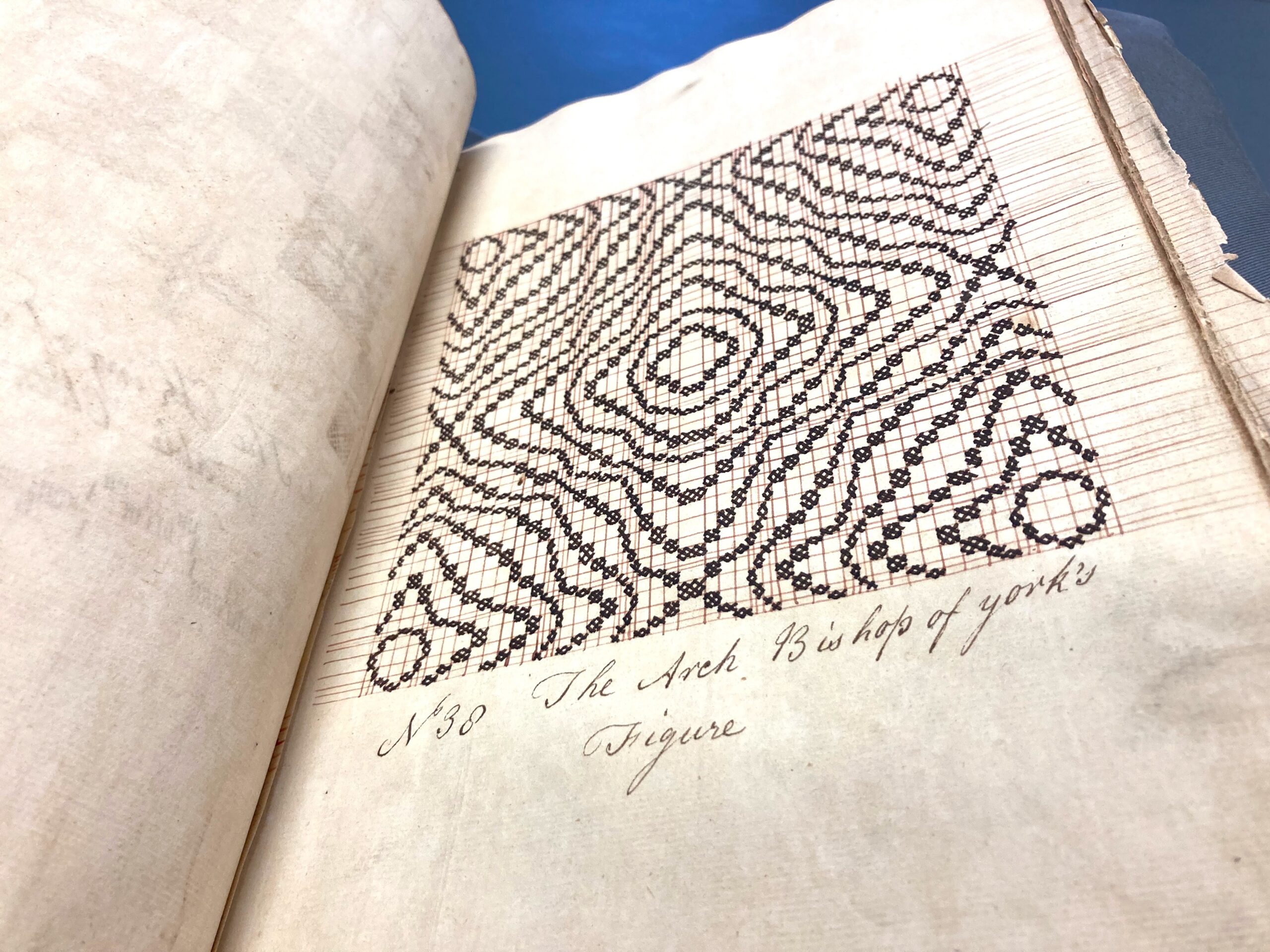

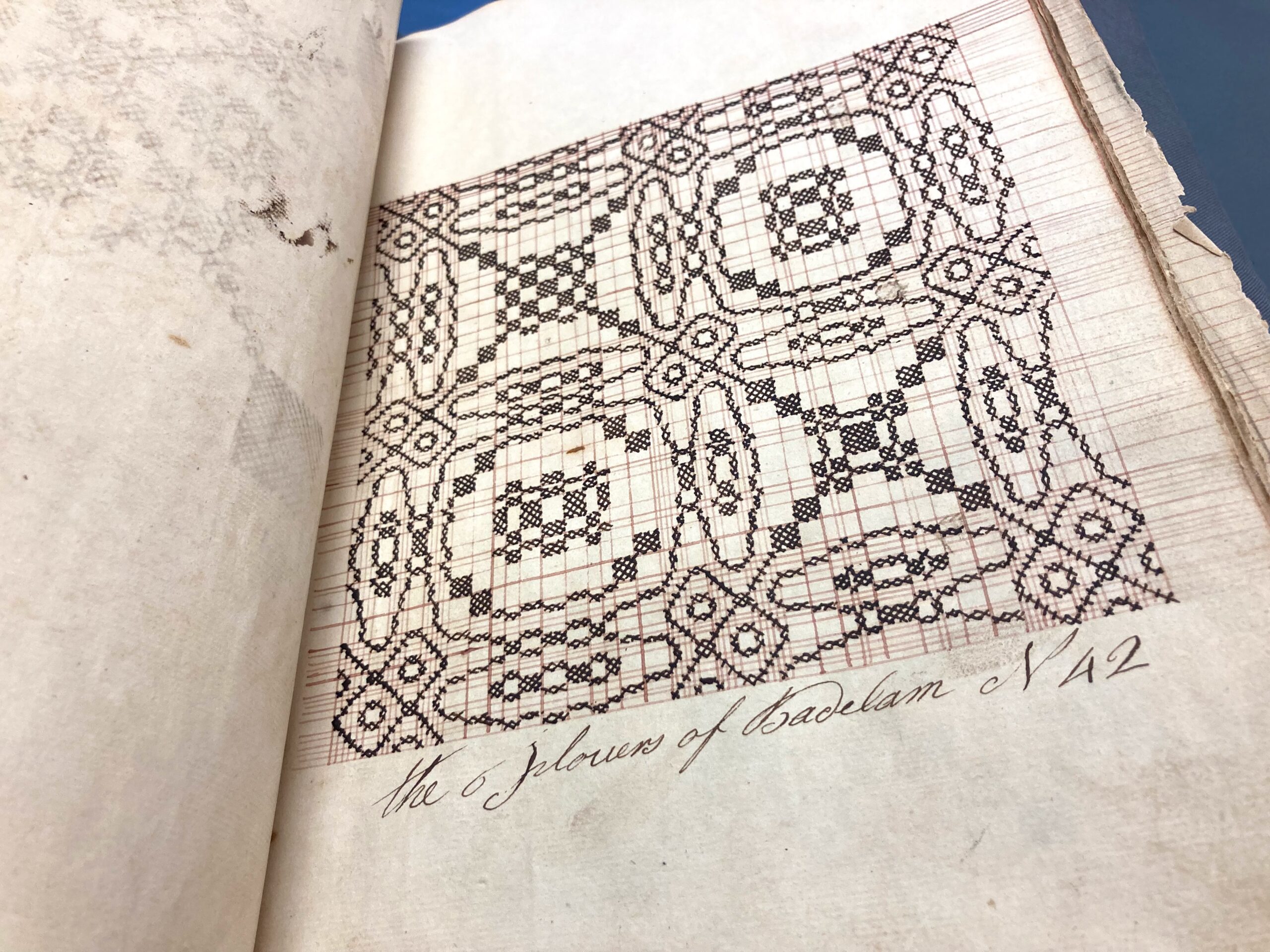

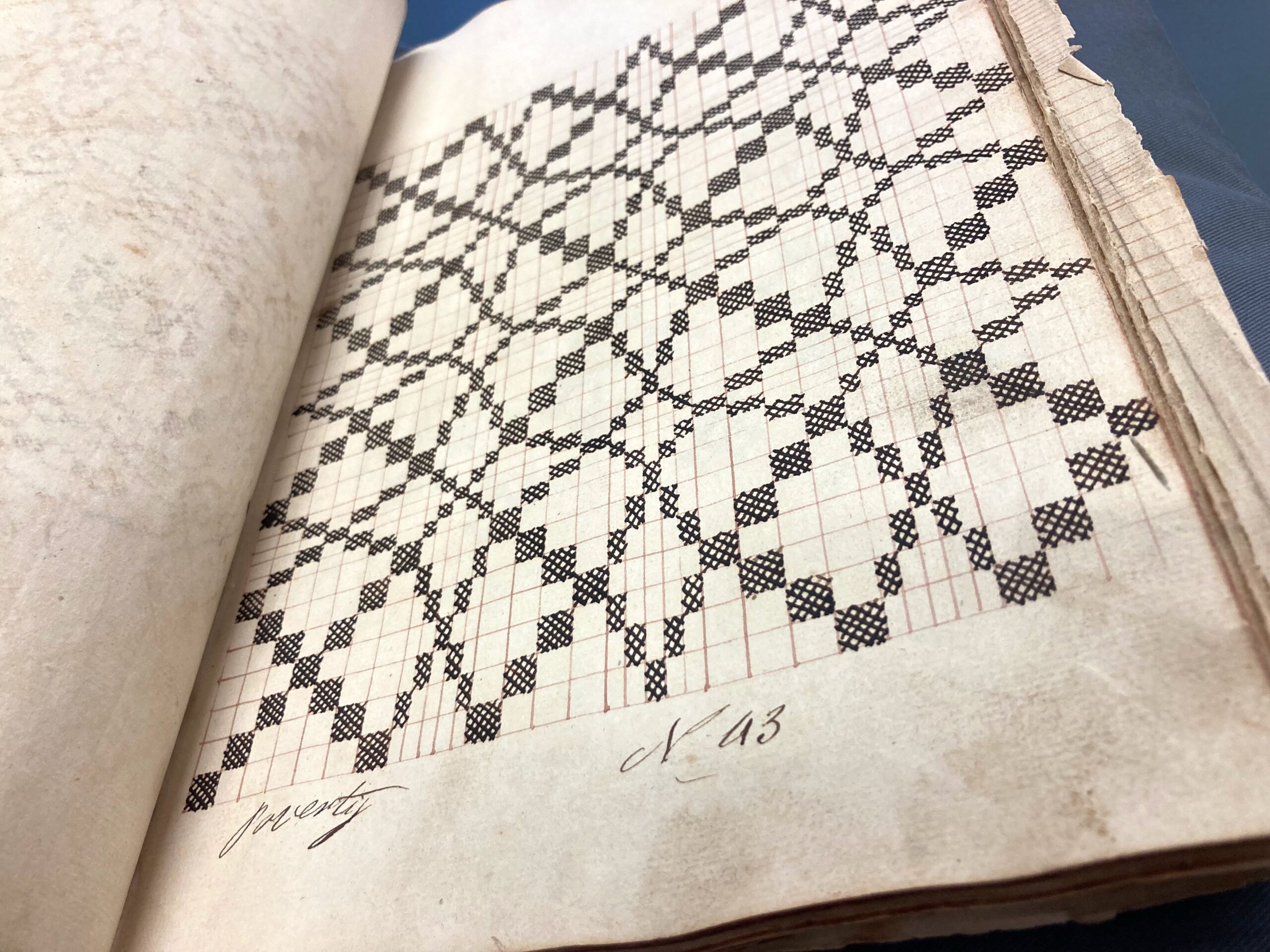

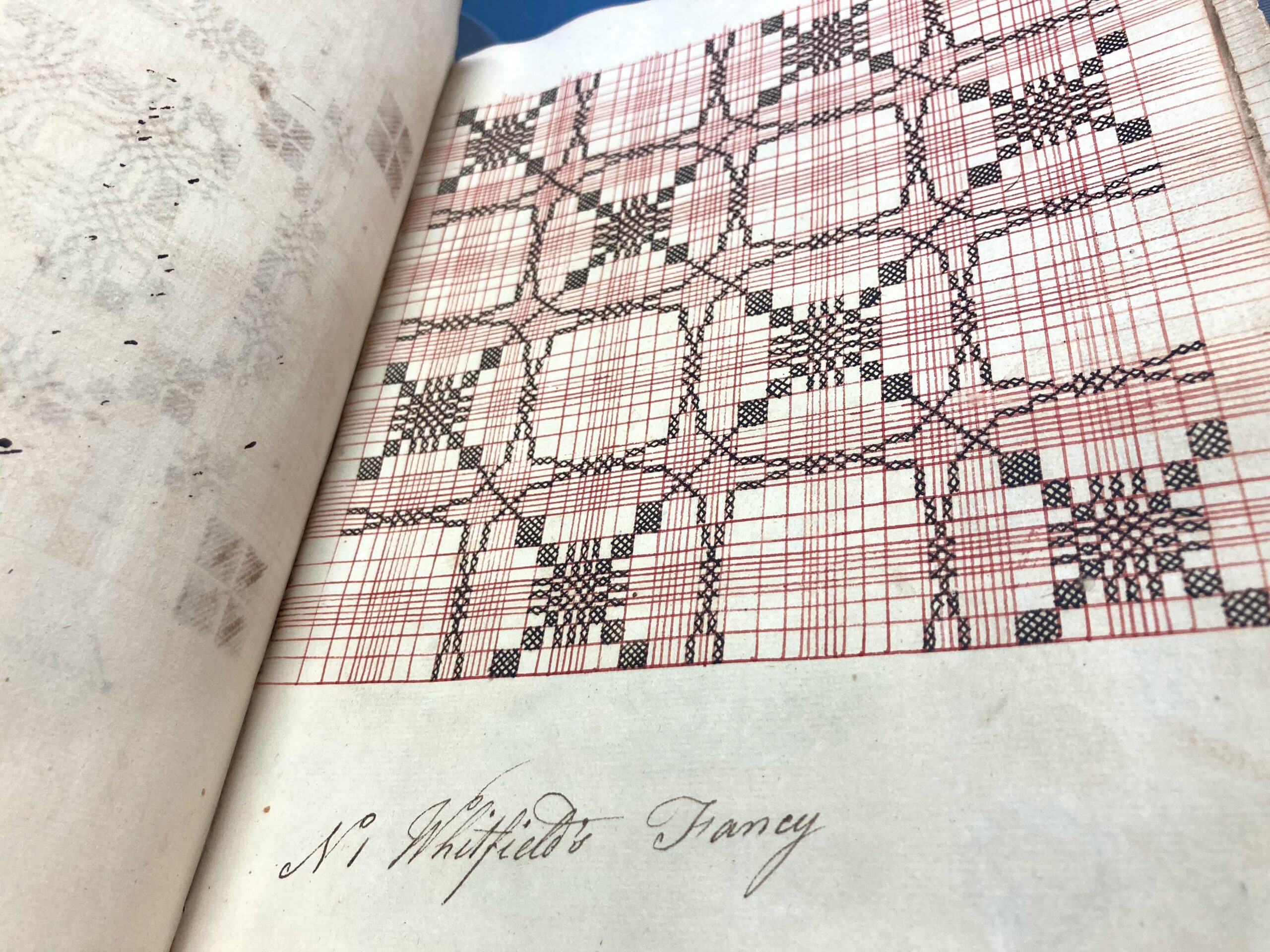

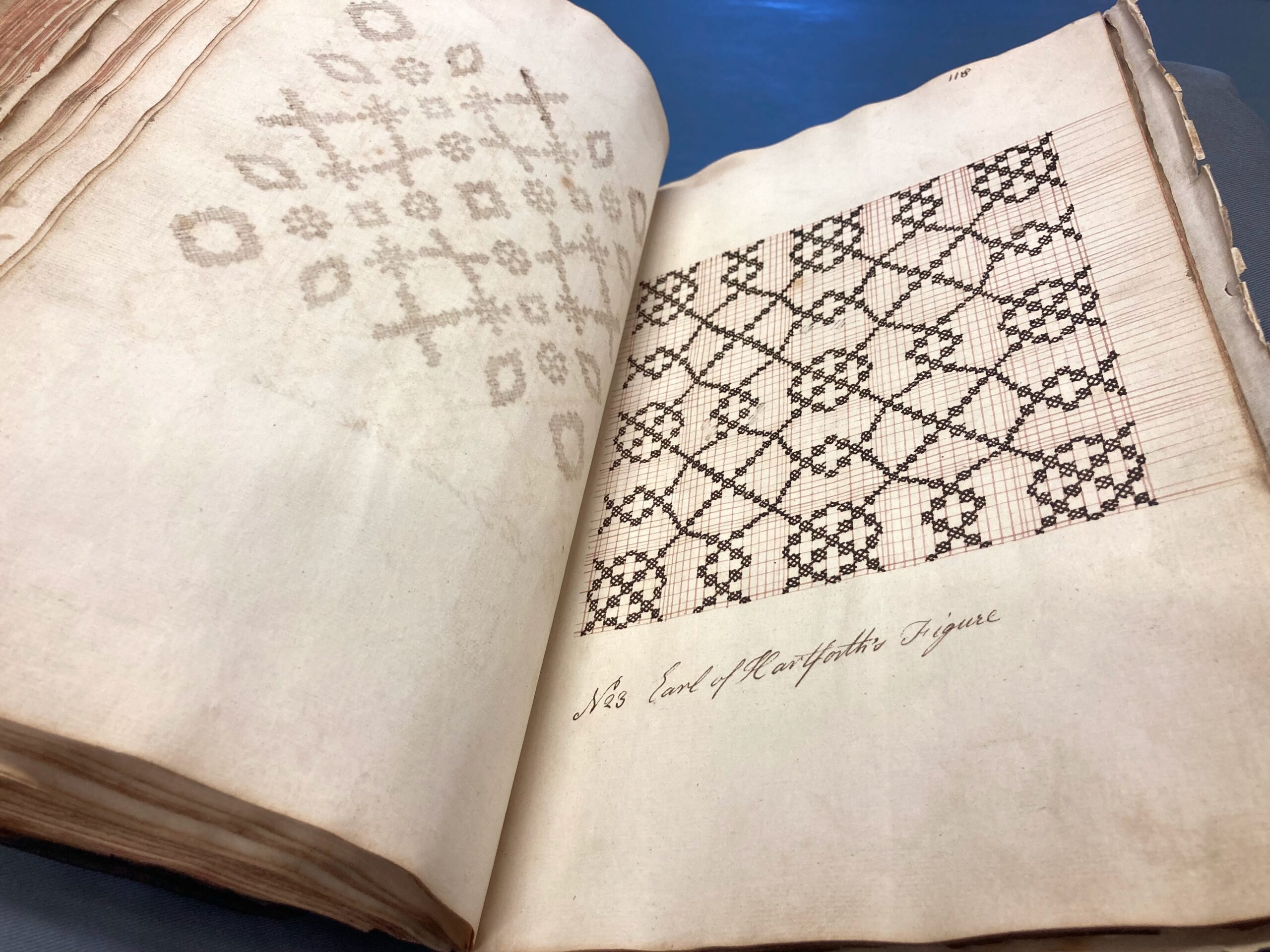

I arrived for my appointment at the County Records Office in North Allerton to find The Weaver’s Guide waiting on a cushion in the middle of a big grey table. The manuscript is about twelve inches high and eight inches wide, bound in brown embossed leather, with one hundred and fifty pages. On the first page is a short introduction inviting potential customers to select patterns to be woven on commission. Most of the other pages are taken up with hand-drawn geometric designs for a type of linen cloth known as damask diaper. The gridded designs are ruled in red ink with black cross-hatching, and each has a title inscribed underneath: The Milk Maid’s Glory, The True Lovers’ Knot, Lady Denbigh’s Fancy, Prince Ferdinand’s Breakfast Cloth, The Deep Wounds of Calder. The last few pages include profile drafts of the diaper patterns and some other weaver’s drafts, including the ‘happings’ that kept me busy for most of 2021.

.

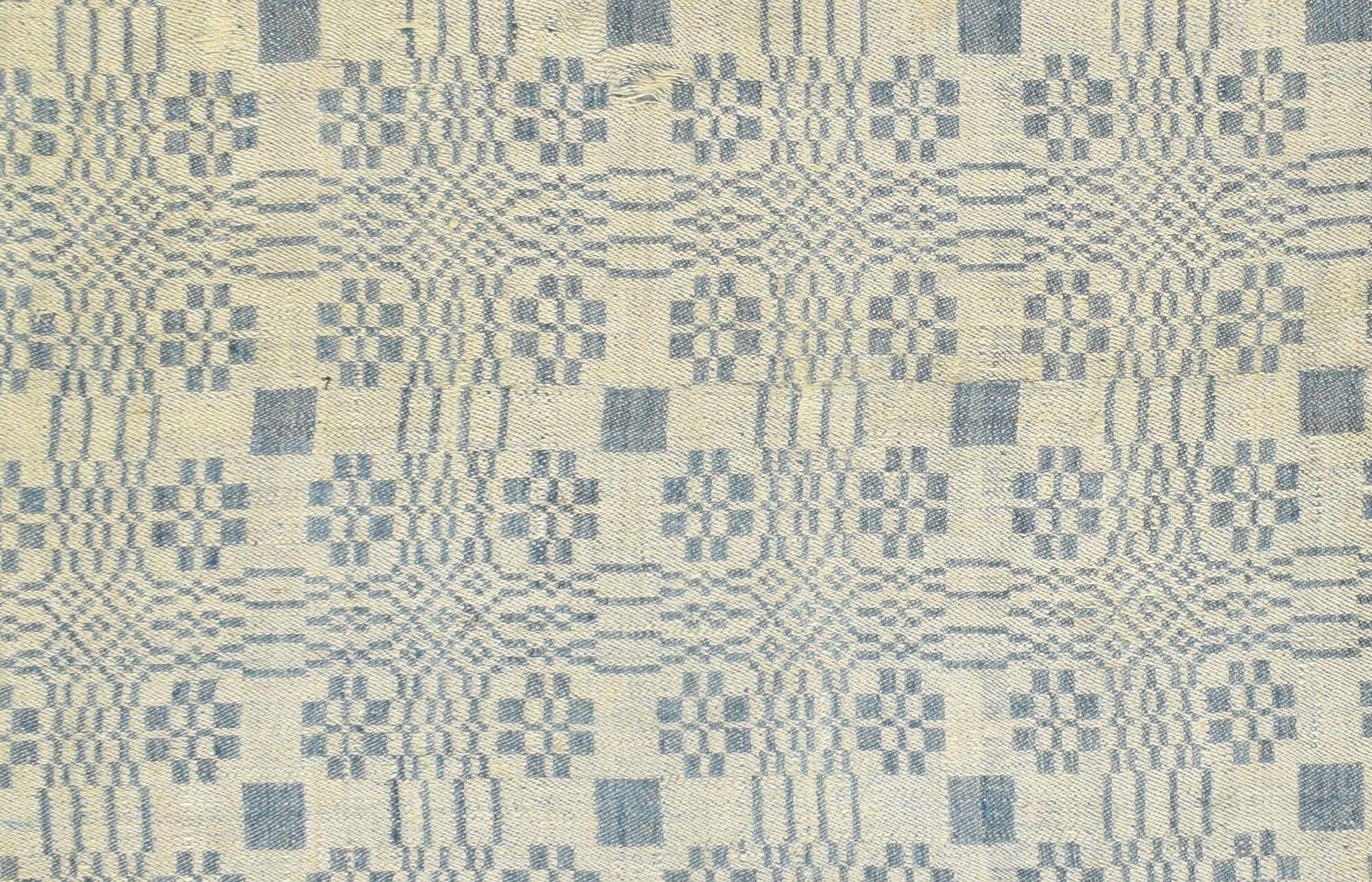

I had acquired black & white digital scans of the manuscript a couple of years ago. I knew it well and wasn’t sure what I would learn from seeing the real thing. It was finer than I had expected, and more alive. The patterns seemed to change as I shifted my viewpoint, just as they would as woven tablecloths. It also occurred to me that the patterns are drawn at roughly one-to-one scale, the same size as the patterns in the woven cloths which they represent. For example, the smallest unit in the pattern called The True Lovers Knot is about 1.7mm square. In the woven cloth this would correspond to five ends and picks, equivalent to a sett of about 75 ends per inch – a suitable sett for linen yarn of about 30/1.

Background

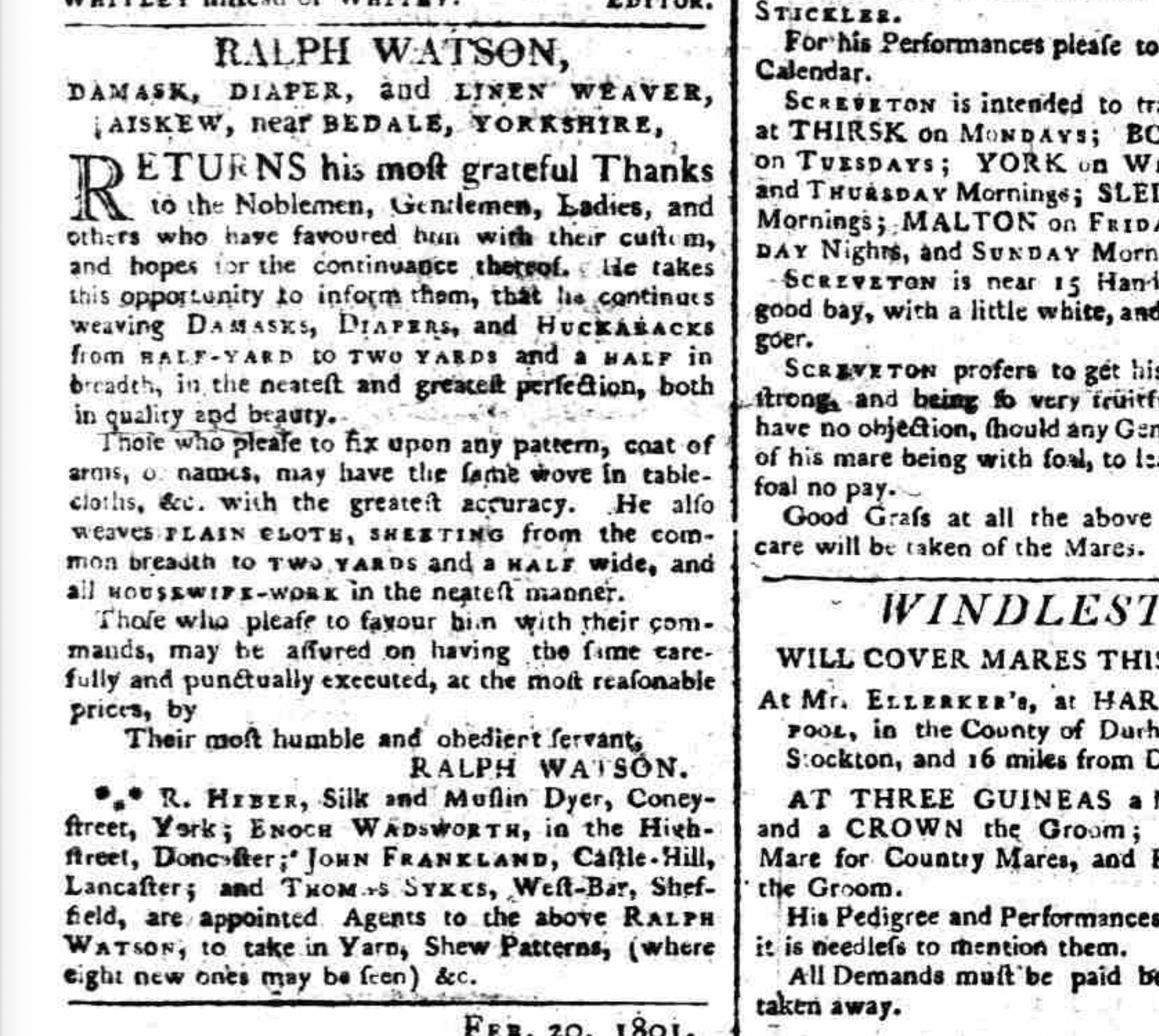

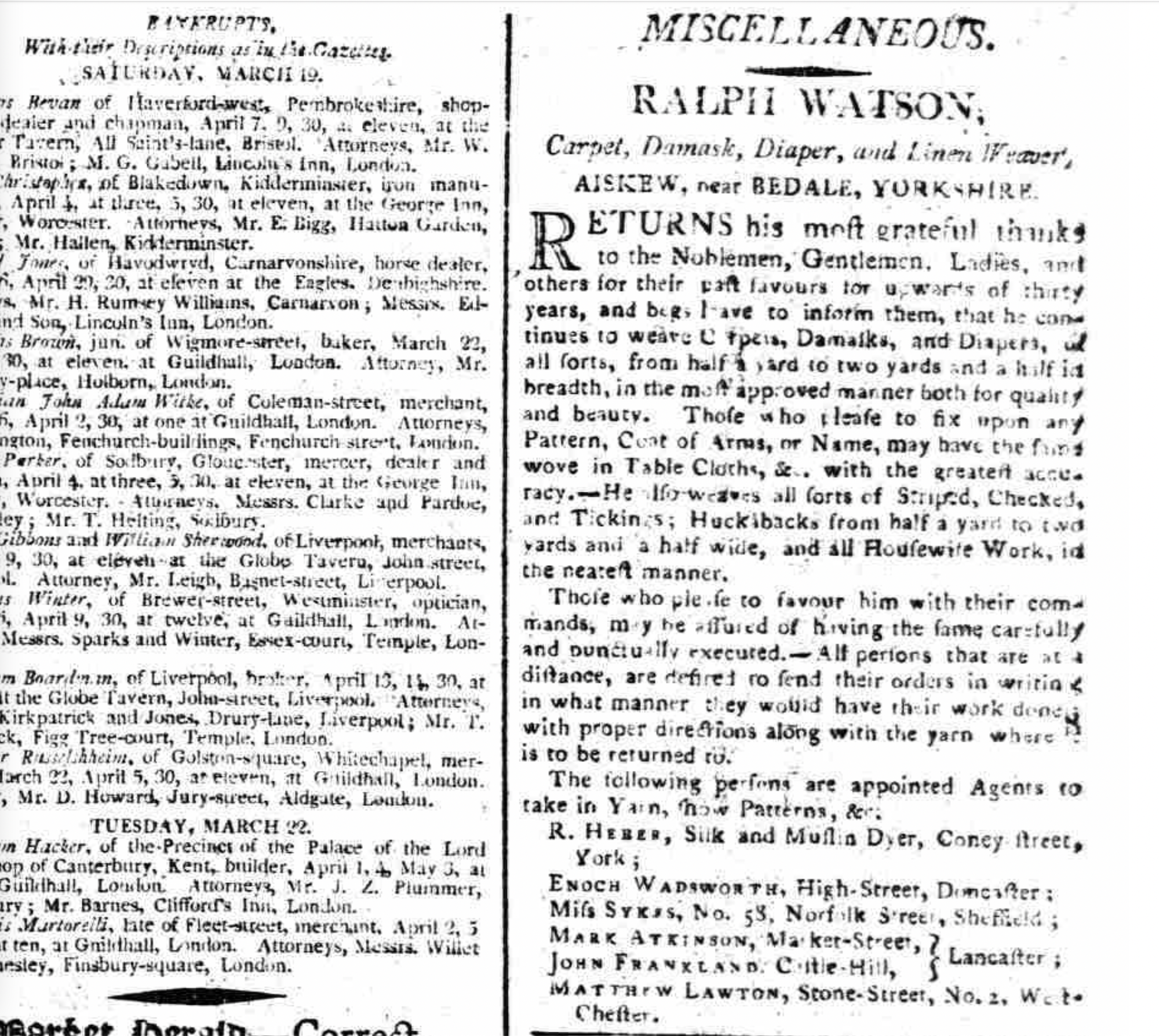

The manuscript was written by Ralph Watson, a linen weaver from the village of Aiskew, near Bedale, at the northern end of the Vale of York, between the Yorkshire Dales and the North Yorkshire Moors. The manuscript is described by the County Records Office as dating from the eighteenth century. It was probably compiled over several years, and before 1805, when Watson’s son-in-law Francis Lodge took over the business. We know from Watson’s headstone in the churchyard of St. Gregory’s in Bedale that he died in 1812 at the age of 64. According to advertisments in the York Herald in 1801 and 1803 he manufactured linen damasks, diapers and huckabacks, as well as plain cloth and sheeting, up to two and a half yards wide. He had agents in York, Doncaster, Sheffield, Lancaster and Chester.

Technique

We know from Watson’s introduction that his designs are for a type of cloth known as damask diaper: “… if any please to Employ me either in Dammask’s or Diapers they may be sure to have them done in the Best Manner any breadth which they chouse, (but the following figures is all for Diapers).”

Damask diaper is made up from alternating blocks of weft-faced and warp-faced twills. Weavers’ drafts at the back of the manuscript indicate that Watson used a five-end satin twill. The cloth can be woven using different colours for warp and weft, creating blocks of contrasting colour where the warp or weft predominates. More often, damask diaper was woven with the same yarn, bleached or unbleached, for both warp and weft. The warp-faced and weft-faced blocks catch the light differently producing a more subtle visual effect.

Unlike damask woven on a Jacquard loom or the earlier draw-loom, both of which control individual threads and can therefore make intricate designs with curves and diagonals, damask diaper is made on a shaft loom and is limited to designs made up of stepped rectilinear blocks. Most of Watson’s designs are based on four different ‘divisions’, although some have six divisions.

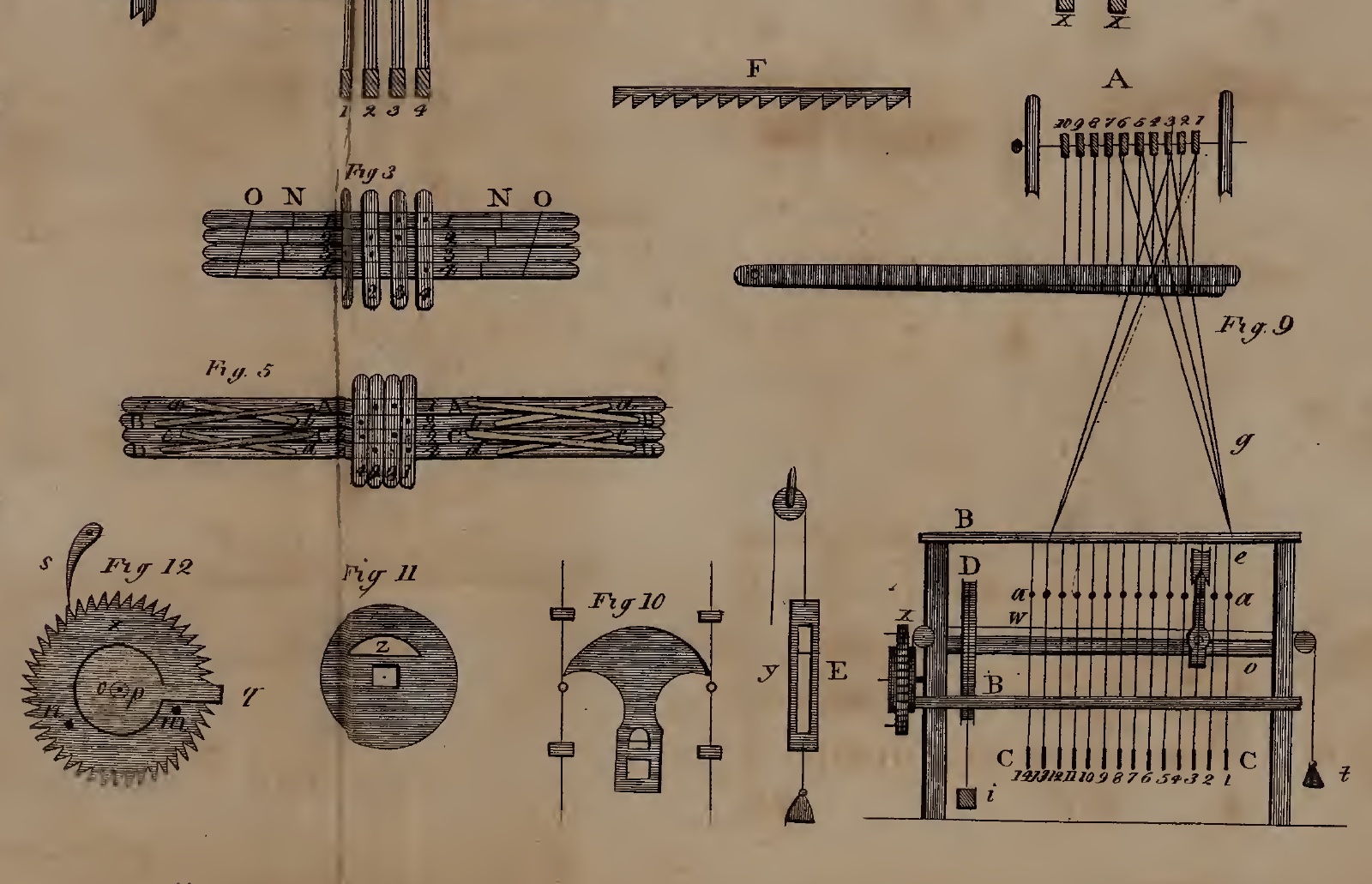

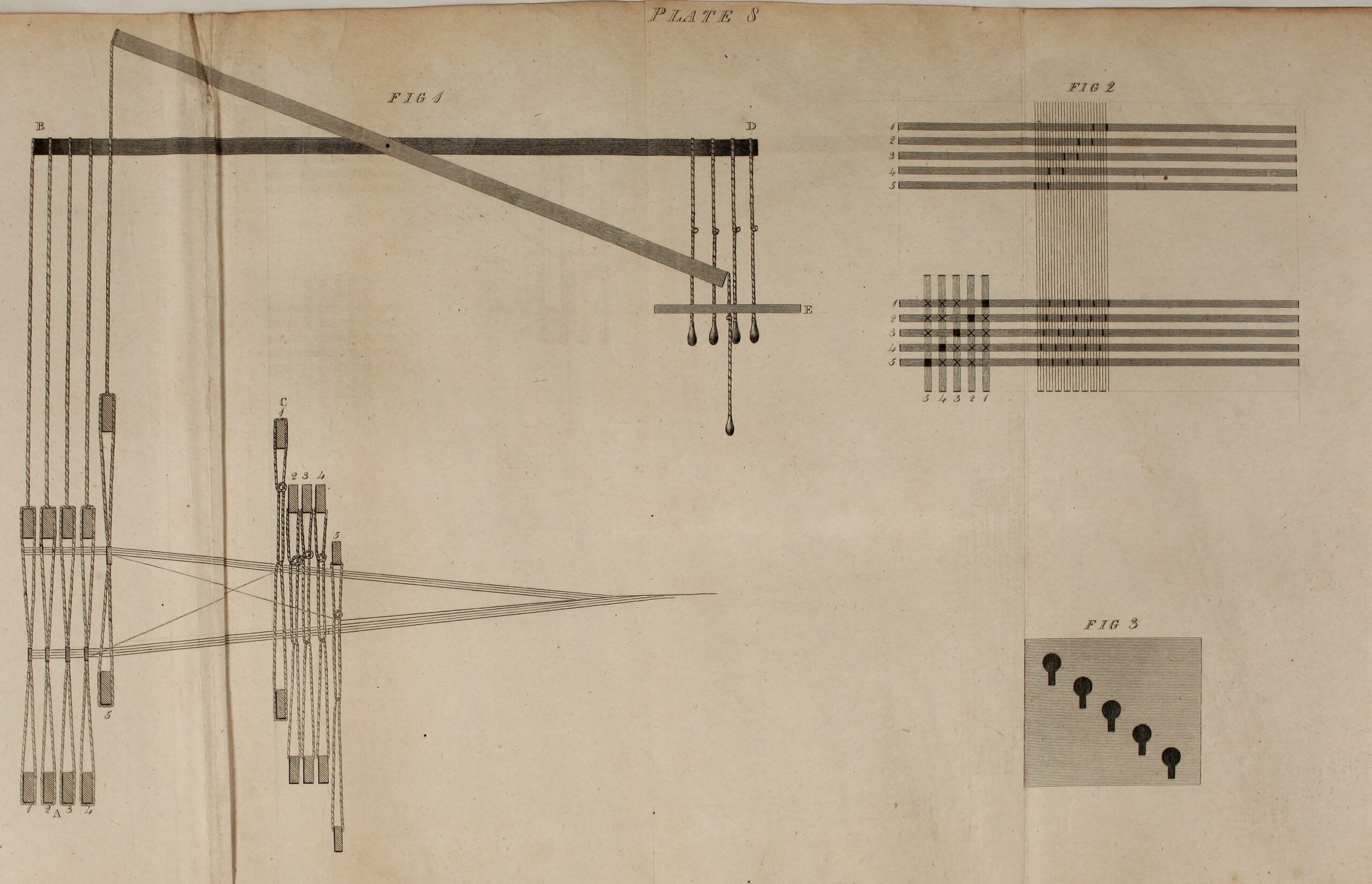

As far as I know there were two ways of making damask diaper in Watson’s time. The first used a loom with two harnesses (groups of shafts, or leaves), sometimes called a shaft draw loom. This has a front harness with long-eyed heddles operated by treadles, and a back harness operated by overhead pull-cords. The front harness forms the satin twill ground weave, and the back harness forms the block pattern. John Duncan includes a description of this apparatus in his Practical and Descriptive Essays on the Art of Weaving (1808). The advantage of this ingenious arrangement is that it can be operated without assistance or complicated mechanisms. However, I am sure this was not the technique used by Watson. Towards the back of the manuscript Watson includes drawings of lifting plans that are incompatible with the use of a double harness. (1)

The alternative to this is a loom with lots of shafts – five for each division of the pattern. Most of Watson’s designs have four divisions and would therefore need twenty shafts. It is generally considered impractical to operate more than a dozen shafts with treadles. By Watson’s time a variety of automatic mechanisms for lifting shafts had been invented. For example, John Murphy’s Treatise on the Art of Weaving (1827) describes an automatic lifting device called a ‘parrot’. I think it likely that Watson had one or more looms fitted with a ‘witch’ engine, an early version of the ‘dobby’. Bradford Industrial Museum has an old loom with a witch engine, and an eighteenth century loom with a witch engine was given to Bankfield Museum in Halifax when the Norfolk linen weaving firm of Buckenham’s closed down in the 1920’s. Both the witch and dobby engines sit on top of the loom. The selection of shafts for lifting is made by pegs called ‘lags’ set into a set of wooden bars linked in a continuous chain.

.

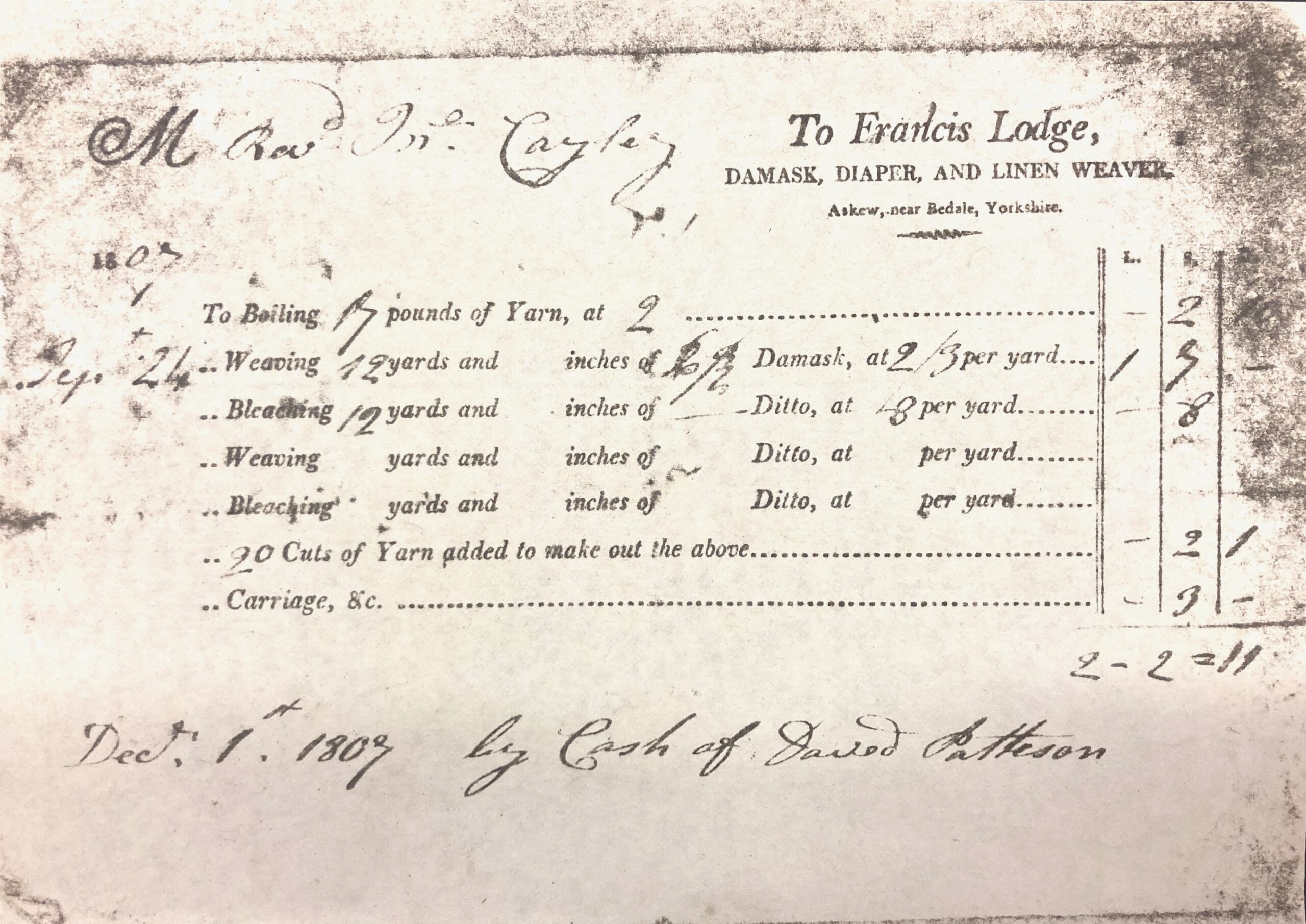

Addenda

Someone has inserted a slip of paper between two of the manuscript’s pages, like a bookmark. The slip is a copy of an invoice, payable to Francis Lodge, Damask Diaper and Linen Weaver, Aiskew, near Bedale, Yorkshire. Lodge was Watson’s son-in-law and had taken over his business in 1805. The invoice is for a total of £2-2-11, for boiling 17 pounds of yarn, weaving 12 yards of damask at 2 shillings and 3d per yard, bleaching the same at 8d per yard, and supplying 20 cuts of yarn “to make out the above”. The invoice suggests that the customer was supplying the yarn, which may have been home-spun. It also indicates that the cloth was bleached after weaving, rather than the yarn being bleached first.